I am in Berlin, struggling to decide on what exhibitions to see on a Saturday afternoon. The London-side of Artupdate's art map looks so much more comprehensible, juxtaposed with the sea of vaguely recognisable names dotted all over the German capital. The layout of the maps is abysmal: a sea of little colour-coded numbers, which correspond in no particularly coherent way to the listings on the back. I go online instead. After some internet research, which leaves me irritable as it seems that all the public galleries have geared their programming towards children and young people (for whom I have begun to develop an irrational hatred of, even though it is not their fault they have become funders' favourite 'target audience'), I come across an announcement the Neue National Galerei's Marcel Duchamp exhibition. 'For 72 hours only' the headline on the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin website screams. I am loath to be enticed by such an obvious sales trick: limit it, make it desirable - it's the old 'for one night only!' snare... On top of that they are only showing one work. I hesitate, but my morning's reading convinces me. I get on the S-bahn to Potzdamer Platz.

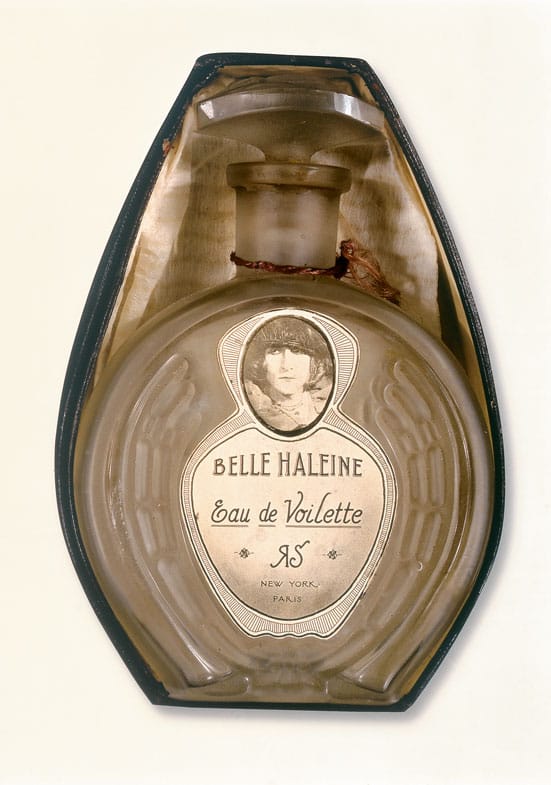

The Mies van der Rohe-designed gallery walls bear the same hyperbolic Nur für 72 Studen! The glass construction is unusually dark, and there is a hushed atmosphere as I press through the revolving doors. The vast space is empty apart from a group of people huddled around a glass case. The pyramid top of the case (the same as the one Nefertiti occupies on Museum Island, the press release proudly announces) holds Duchamp's assisted readymade Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette (Beautiful Breath: Veil Water) from 1921. It's a Rigaud perfume bottle, bearing a gold label attached to the back of the box with the inscription with the inscription: 'Rrose / Sélavy / 1921.' It shows an image of Marcel Duchamp face, dressed in women's clothing as his alter ego, photographed by Man Ray. It's 7.9 million Euros of perfume bottle, the sum it was sold for at auction in 2009. It is quite pretty, though it is hard to get any impression of the tiny flask through the reflective glass (not aided by the fact that people keep photographing it). In fact, it looks better in the picture (shown here for your benefit). I feel foolish for having trekked all the way. I blame Agamben. Well, partly.

A number of people have pointed to Duchamp's elevation of mass-produced objects as a major turning point in how we view art. Craftsmanship became irrelevant, replaced by the artist's intentionality, the concept, or perhaps the viewer's interpretation (if you were post-modernistically inclined). It's a familiar story in the history of contemporary art. The assisted ready-made elevates the artist's gesture further: a little alteration confers exclusivity onto the object, in the case of Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette onto an already exclusive consumer product. What distinguishes Agamben's approach in The Man Without Content from many other views on Duchamp's influence is that he suggests that this ushers in a certain crisis in how we view art. For Agamben art was always defined and situated in relation to its shadow (non-art), but, following Duchamp, art and its display has not only embraced this shadow, but has actually become it:

“The extreme object-centeredness of contemporary art, through its holes, stains, slits, and nonpictorial materials, tends increasingly to identify the work of art with the non-artistic product. Thus, becoming aware of its shadow, art immediately receives in itself its own negation, and in bridging the gap that used to separate it from criticism, itself becomes the logos of art and of its shadow, that is, critical reflection on art. In contemporary art, it is critical judgment that lays bare its own split, thus suppressing and rendering superfluous its own space.” (Giorgio Agamben, The Man Without Content, p. 32)

Whereas that critics in the 19th century fussed over whether something was or wasn't art, i.e. whether it could be distinguished from non-art, Duchamp's readymades circumvented this logic, ushering in a new approach to how art – the beautiful even – was assessed. Nevertheless, some critics continue to assess art according whether it fits into either of these categories, asking the utterly uninteresting, defunct question 'is it art?' which is particularly prevalent in TV programmes on contemporary art in Britain. In addition to reading about Duchamp that very morning, part of what fuelled my visit to the Neue Nationalgalerei was one of the Hamburger Bahnhof's current listings – also on the Staatliche Museen website – one of the few 'events' that was not targeted towards children and young people entitled 'Was is Kunst?'. The irony of having this inane question listed next to the announcement of Duchamp's Neue Nationalgalerei seemed prescient. However, any smugness gleaned from this discovery it was eclipsed by the sense of embarrassment of being ensnared by the hyperbolic, exclusionary draw of the display of Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette. Much as I felt when I joined the hoards visiting Damien Hirst's skull For the Love of God (2007) at the White Cube Mason's Yard. Duped by the glitzy headlines, fretting about being left out. Man without content, indeed.

Natalie Hope O'Donnell

Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin. Photo: Natalie Hope O'Donnell (2011)

Marcel Duchamp Belle Haleine: Eau de Voilette (Beautiful Breath: Veil Water), 1921 Assisted readymade: Rigaud perfume bottle with label created by Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray in original box; inscribed on back of box: Rrose / Sélavy / 1921 Private collection © Succession Marcel Duchamp / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2011 © Man Ray Trust, Paris / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2011

Marcel Duchamp Belle Haleine: Eau de Voilette (Beautiful Breath: Veil Water), 1921 Assisted readymade: Rigaud perfume bottle with label created by Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray in original box; inscribed on back of box: Rrose / Sélavy / 1921 Private collection © Succession Marcel Duchamp / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2011 © Man Ray Trust, Paris / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2011