Could you tell me about White Rainbow, the new gallery for Japanese contemporary art in London, which has just opened?

Under the directorship of Yukiko, Fumiko and I formed a team that felt the urge to showcase Japanese artists: there is little opportunity for them in London compared to New York, Los Angeles and Europe, where Japanese post-war avant-garde artists have stronger and longer-standing connections. The revival of these artists’ presence in the international art market is quite evident today, and the artists and artworks of Jikken Kobo, Gutai and Mono-ha have been presented by various established galleries and museums and in public programmes recently. But how about the younger generations? How about the established figures who may not be part of a major art movement recognised outside Japan? We aim to present work on its own terms, and people can judge it for themselves.

It is indeed true that the team is not based in Japan. I personally had a longstanding issue with whether I deserve to play the role of local informant. Now I am in the team of Yukiko and Fumiko, I have decided to believe that our presence is to channel the overall picture of the art scene with our longstanding admiration for artists, curators, writers and dealers who have developed their own language that fascinates us, and to convey it to a London audience. We have chosen to present mainly Japanese artists in this gallery and we are aware that some might view this as a nationalistic gesture. Personally, I have waited during the last decade to see how non-Japanese curators would develop relationships there, and how I would progress in my career … then I could wait no longer as there were a lot of interesting young artists and I wanted to challenge the perception of contemporary art from Japan, and to present the different voices raised by individuals. The first show at the gallery (and its project beforehand) is by Aiko Miyanaga.

Could you tell me about the current show by Aiko Miyanaga? It was great to rediscover here her installation Strata: Origins of objects cast in naphthalene that I first saw at the Central Liverpool Library during the Liverpool Biennial. The works took on a very different character installed around a concrete pillar to when I had seen them in the wood-paneled library. Transformation is an inherent part of this work, as naphthalene is a volatile compound that changes in response to temperature and humidity. Could you tell me a little about the artist’s working method?

Aiko has been working on the naphthalene for sometime and it varies not only in its form but the thinking behind each work: the pieces enclosed in glass boxes, the cast naphthalene keys and clocks that, once exposed to the air, begin a process of sublimation into the atmosphere. It crystallises and recrystallises endlessly, so the original shape of the objects may be transformed but it does not mean the artwork has vanished. Some may describe the work as unstable for works of sculpture because the shapes created by the artist change constantly, but we can also describe the transformation as the adaptation and stabilising within a system: this idea particularly touched us because our island nation has to face natural disasters regularly, and, literally, commodities, and indeed our bodies (metaphorically the media attention too), are washed away: but our thoughts will stay with us and can transcend. We also see her adaptation of the environment as a form of resilience and I respect Aiko for not making a video work, as we cannot easily clock back or forward from the past to the future.

We felt it was important to present her work in Liverpool because the port city went through a lot of changes and adaptation from other parts of the world in its past. London has the same ethos, but the venue of the library was just perfect. (Of course, the forward thinking, supportive staff there made the exhibition even better!) Books by Aiko do not contain words, but when we are reading, we don’t follow each word. We instead integrate the ideas and imagination, and place and time that authors write of. We felt the assimilation of her thoughts on the library to our motivation of our gallery: a library is composed of strata of information – presents consisting within pasts. Where we stand by to observe, and what we choose to read represent certain boundaries and reflections of thoughts. We are not here to only present exhibitions, but to contextualise elements of Japanese contemporary art history through our programme.

I also loved Miyanaga’s installation soramimimisora, of three ceramic bowls balanced precariously on a glass shelf atop a ladder. She explores the passage of time as well as the rejection of perfection in this playful sound work. When newly fired the bowls were exposed to cold air which creates a ‘crazing’ effect, considered a defect in traditional ceramics. The bowls will continue to crack audibly over years. Is a fascination with such barely perceptible changes a constant in the artist’s work?

Chance encounters or awareness of the surrounding … it sounds really John Cage-esque, doesn't it? If I may add, I would like to share Aiko’s personal history of how the artwork was originally conceived. Being brought up amongst generations of a famous kiln family in Kyoto, the beautiful crazing sounds meant ‘emotional stress’ for her family – as you have noted, these fissures are considered unstable for decorative purposes (or defects in her father’s renowned smooth perfected sculptural ceramic pieces), so the actual crazing has to be settled or hidden away prior to its public presentation.

In my view, she resuscitated her own memory with the question of what good and bad is – the objective answers by personal perspectives – by presenting the crazing outside of the ceramic practice. We can appreciate its process of endless equilibrium: the shapeless invisible sound will grow to have its own space through your imagination and the act of listening intently. This crazing technique is also used as a decorative purpose in the industry, so Aiko purposely placed it above our eye level – because it is not about admiring the decoration or form. However, if you see the fissures on the bowl, it is almost like they create a whole new map – the exhibited editions were fired in London (with thanks to London Sculpture Workshop) and remind me of the colour of the horizon of a clear sea. The depth of the glazing with its cracks also appears like tides and the shallower area is like a delta.

What are your plans and ambitions for your first year’s programme?

The next one is our first group show, opening in December, called Temporal Measures three artists [Futo Akiyoshi, Kouichi Tabata and Takahiro Ueda] who are engaging with the physicality of their medium to articulate dimensions of time, layers of space, and realms of the mind. The very next one is Chu Enoki – he is much respected by Japanese artists and I personally believe that he has developed the notion of performance art outside the direct influence of the theatre form.

Having said this, we are very much looking forward to working with non-Japanese artists in the future. We have invited guest curators to do special shows and it is entirely up to them to select the theme – we believe there are synchronicities in social issues or ideas beyond nationalities, especially today, but in the past too. These collaborations with exciting curators are very important, because we would like to have fresh eyes, building the relationship with curators and artists beyond nationalities, and would like to bring a surprise to the experts in Japan too.

Is there a strong link between the art scenes of Japan and the UK at the moment?

I feel there are stronger ties at the moment, which is very exciting. One of the most exciting projects I have heard is … I am not sure I am allowed to mention it! But a particular non-profit project space in Japan, which I respect because of their contribution to bringing a certain maturity to its art scene and making the imagery of contemporary art more familiar, are currently organising an exchange with my favourite institution in London: presenting British artists in Japan and Japanese artists and curators in the UK. On the other hand, a lot of things were built by years of efforts by individuals and institutions, such as the Abe fellowship by the Japan Foundation and The Daiwa Art Prize by the Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation, and some scholars and writers who we value highly for their lengthy and selfless support of those exchanges.

What is your own background and experience as a curator?

I must confess that I don’t see myself as a curator, with respect to the role. I was fortunate enough to study under my muse – I knew that I wouldn’t get taught how to be a curator and nobody could make me one. But being surrounded by passionate young curators under her directorship, I learnt a lot in various aspects: being tough, being curious, being adaptable, being grounded and facing my fears. But most importantly, respecting others’ ideas and believing in them – I see the responsibility that I am likely to be the first audience, before then presenting to a particular audience. It is very exciting and scary at the same time. Talking to artists brings me confidence in presenting them for shows, but I also need to be even more confident, to at first ask questions on behalf of the audience.

I have been growing my interest in what a healthy relationship between artists, curators and audience is. After working for biennials and a triennial, and then a newly opened public gallery in the north – I was fascinated by how cultural strategies operate in different regions. This led me to take the sidetrack to work at the Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation, even though the main focus is not the arts at this organisation. But the reason I was interested in contemporary art was its affinity to societies and cultural climates, so working for the events programme, which covers topics of politics, sociologies, economics and education was very valuable for my current position.

Ali MacGilp

Aiko Miyanaga

Installation shot of Strata: slumbering on the shore at the Liverpool Central Library, 2014

Mixed media

Courtesy of the artist and White Rainbow

Image: Leo Bieber

Aiko Miyanaga

Installation shot of Strata: Origin, 2014

Mixed media

Courtesy of the artist and White Rainbow

Image: Trent Bates

Aiko Miyanaga

Installation shot of soramimimisora, 2014

Sound installation

Courtesy of the artist and White Rainbow

Image: Trent Bates

Aiko Miyanaga

Installation shot of soramimimisora, 2014

Sound installation

Courtesy of the artist and White Rainbow

Image: Trent Bates

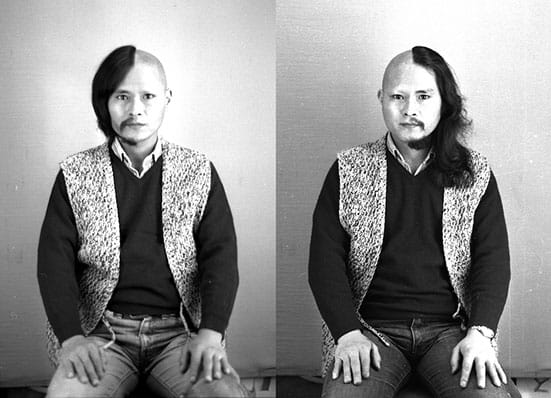

Chu Enoki

Going to Hungry with HANGARI, 1977

Performance

Courtesy of the artist

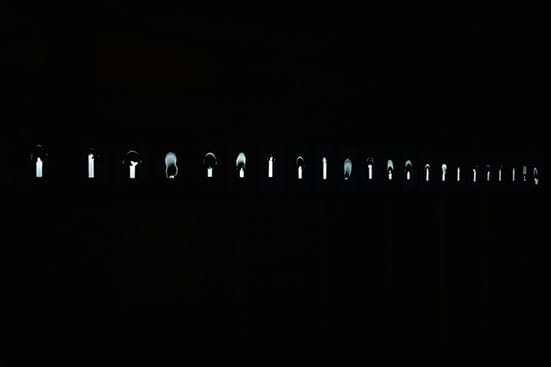

Takahiro Ueda

Installation shots of Invisible Movement, 2013

Quartz, analog clock, steel, acrylic board, wood, signal generator

Courtesy of the artist

Image: Shinji Minegishi

Kouichi Tabata

Installation shots of 72 Colors (Rose), 2013

HD video and a set of 72 colour pencil works on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Koyanagi

Youki Hirakawa

Installation shot of Fallen Candles as part of Nuit Blanceh Video, London, 2014

24 Channel Videos / Approx.30-45 min Loop / Full HD / Silent

Courtesy of the artist and White Rainbow