Interview with Cassandra Needham, John Jones Project Space Curator

What is your vision for John Jones Project Space?

The focus for John Jones Project Space is on emerging artists, but this can be both national and international, and artists who work in any medium and across media. The Project Space is intended to provide a platform for artists at a certain point in their career; where they've already developed an exciting practice, they are very well-respected by their peers and those who know their work well, but they could do with that little extra exposure. If we can assist further with all the facilities and services we have within the John Jones business then that is even better. This all ties into the long-term philosophy of the Jones family to nurture young talent. Selfishly, for me it is about working closely with artists, to assist in the realisation of their projects through conversation and logistical support. All the works we've shown to date are new pieces specifically created for the Project Space, which also is very telling of our ethos.

So I suppose in summary, our programme is very artist led. I want John Jones Project Space to be an artist's gallery: a space in which artists want to exhibit because of its strong reputation, the freedom offered and because we are dedicated to collaboration. I strongly believe that that is the key to a strong programme and healthy visitor figures, it is also the ethos behind John Jones the business. I think that is why the Project Space works within the context of John Jones - because we share a process-led approach to our work, and our vision is led by artist practices.

Could you tell me about the context of the Project Space in the new Arts Building in Finsbury Park?

The Arts Building in Finsbury Park is the new headquarters for John Jones, a second-generation family business that has bespoke framing at its core. John Jones was established as a framing company in the 1960s with clients including Francis Bacon, Paula Rego and David Hockney. The business relocated to Finsbury Park about thirty years ago, just behind our current location. Now John Jones offers a broad range of Art Management services including fine art conservation, installation, display services, high quality printing and much more. The building itself is designed by David Gallagher Architects and its New York warehouse influence makes it elegant and impressive.

I curate the art programme which includes the exhibition and events programme in the Project Space, as well as an artist-in-residence programme, professional development opportunities for artists and community outreach. The art programme, and therefore the Project Space, is not-for-profit and it is intended to give back to the art community and the local area. Finsbury Park is still one of the poorest wards in the country, so we take our responsibilities very seriously. John Jones is working closely with Islington Council and other cultural organisations to provide positive change and opportunities to the area. The Project Space is one of the more visible aspects of what is happening.

What are your personal priorities for the programme at John Jones Project Space? What developments would you like to see in the future?

I think I have already touched on this so I will keep it brief. My personal priorities are quite simply to curate a programme that has integrity. I want the Project Space to be respected by artists and art professionals, and for it to be visited by a broader public. I also want our audience to have a meaningful engagement with the art. I think Raven Row is a great example of how a contemporary art gallery can build an enviable reputation founded upon artistic integrity.

It would be really amazing if the artists who participated in our programme one day look back and think of their project at John Jones as a defining moment in their practice. Maybe that could happen because they tried out something new for the first time. For example Teresa Gillespie's performance with us was the first time she performed a spoken word piece actually within the installation itself. She told me that this was the moment that particular work became complete. Or because it enabled a level of professionalism which took them to the next level. Who knows, but that would be really something.

My priority for the future is an outreach programme that provides a meaningful interaction between communities and artists. How to integrate this with the exhibition and event programme, as well as how to resource it. That is what I am currently researching. For me, it feels like a much tougher and complex role, and not something to be taken lightly.

Could you tell me a little about your background and experience as a curator?

I initially studied as an artist (specialising in painting) before completing my MA in Curating Contemporary Art at the Royal College of Art in London. For me, coming from Wales, the course was a real eye opener. Since then I've worked at some of the most well-respected galleries in London, including the Whitechapel Gallery, The Serpentine Gallery, The Barbican Art Gallery, and most recently Nottingham Contemporary, working my way up from Assistant Curator. It is a very hard transition to make from Assistant Curator to Curator, especially for a woman.

My first 'break' was when I worked on Parts III and IV of the Whitechapel's Short History of Performance series - Part IV involved fourteen complex video installations (by artists such as Barbara Kruger, Aernout Mik, and Eija-Liisa Ahtila) which changed every day over a fortnight with us installing and deinstalling over night. From that I learnt that if you were going to make something seemingly impossible happen then you had to just work hard and make it happen. Keep the dithering to a minimum. Of course, I was working with one of the most amazing teams. I've worked on hugely ambitious shows and through that I have learnt the ropes. I've also worked independently on exhibitions and as part of norn. The independent shows have always been very important to me as it provides the opportunity to truly think about what you are doing curatorially which often becomes overshadowed by so much other stuff in institutions.

This new role at John Jones Project Space is an opportunity to test out everything I have learnt in the last ten (or more!) years in a very different context. It is exciting. There is a lot of room for failure but huge scope for success, which is ok as that ties into our vision for John Jones Project Space; as a space where artists (and by default curators) can take risks.

Interview with Teresa Gillespie

Her exhibition return to the borderland bends was at John Jones Project Space 5 June – 26 July 2014

How was your experience of being the inaugural show for the John Jones Project Space with your exhibition return to the borderland bends. How did your process unfold? Did you create a work in response to the specifics of the space or were you presenting ideas you had been playing with for a while?

Being the inaugural show at the John Jones Project Space was a pleasure. It brought with it many privileges, primarily the amount of time that I got to spend familiarising myself with and working in the space due to there being no other show beforehand. The result of which meant the work had a chance to extend, sprawl and crawl into the space. The longer I have to install the more occupied a space becomes and the more conditioned the work is by the space, which brings me straight to the latter part of your question concerning the influence of the space on the work.

I find it impossible not to respond to a space, but what I respond to is generally quite subtle, nearly subliminal. I spend time walking through the space, finding points and paths and perhaps most importantly thresholds that I accentuate or interrupt. The John Jones Project Space is unusual in that it has three entrances which had me consistently circling a triangle. My response was ambulatory, ambient and I guess formal. The exhibition space rarely influences the conceptual content directly. I am resistant to my work being inherently specific to a space in that it can suggest a categorical belonging that negates my interests in the migration of matter, blurring of boundaries and continuity below human demarcations. My resistance is weirdly specific and active, while admittedly a little confused. It is partly addressed in a forthcoming publication on the project rogue occupation that took place just before return to the borderland bends. In retrospect and in terms of the relationship between a work and the space it is shown in, the word occupation is perhaps problematic as it puts power primarily in that which occupies, denying the power of location to incorporate, expel and resist. The rogues from rogue occupation, that might be described as balls of matter, rolled into return to the borderland bends and are rolling into the current project, but in each case they accumulate and shed layers. Matter is matter, but it is subject to the conditions of the context. With regards to my practice, the context includes the thoughts specific to any one project, the material contents of my studio and computer, and the space in which the work is shown. For return to the borderland bends the rogues were superficially domesticated through a change in colour that was cracked and dissolved by the chemical reaction from below, they were perforated from the outside, deflated from the inside and exuded paint, latex and rope.

My manner of responding to and negotiating a space primarily concerns the material objects within the installations. The video and audio are generally portals to elsewhere that pierce through the space and interrupt a purely formal reading of the objects suggesting the conceptual content. In the case of return to the borderland bends the videos addressed the body through close-ups with an emphasis on touch, erotics, disgust, consumption, expulsion and animality. They suggested a domestic sphere, which in turn emerged materially around the rogues in the form of a towel, bathrobe, bath mat and duvet, again referencing the body and the transgression of cleanliness by contamination.

return to the borderland bends landed between projects working with particular texts and situated within the development of larger projects. I instantly took Cassandra’s invitation as an opportunity to get some distance from these projects. The borderland bends has become a fictional place I go to stop chasing thoughts and let thoughts invade. It’s a no man’s land or a wasteland characterised by whatever excesses either side spill into it. Nothing is privileged, at least not to begin with, and yet everything matters as matter. It’s when I read the unread books from my shelf, trawl through photographs and video clips that got pushed aside because I was blinded by the path elsewhere and I see the bulging heap of junk mixed with half finished work that is expanding from a corner in my studio. It’s the place I get faced with my practice beyond the fixation and goal of a specific project and where the remains of various projects have merged into a compost heap that begs the question - what’s the difference? Or, what is this pile of mulch? In the case of return to the borderland bends, the mulch included a cacophonous accumulation of voices - primarily Clarice Lispector, Ben Woodard, Georges Bataille and Julia Kristeva - that were partly exorcised through the closing performance. While the consumption and excess suggested in the work was perhaps dominated by the bodily, the studio process was plagued by the problem of my own desire to produce and the sense of my productive being as toxic. The process fluctuated between being a mental war zone and a material playground. Both of which were essential before stepping into the frame of the current project.

While I often work with theory and philosophy, my practice is process led, particularly when wandering the borderland bends. I think through making and make through thinking, which means the process never really stops. Cassandra was very trusting, which in turn meant I invited her into the process more and more. She was very much part of the journey and I think she got a real sense of my practice. She was wonderful to work with throughout and I am very excited to see how the John Jones Project Space develops through her approach.

How was it to return to London, where you studied, from Dublin where you are based, to work on this project?

Returning to London was great and really interesting on many accounts. I have shown in London since leaving but it has been a case of arriving, installing and departing. With this show I was moving back and forth and staying for longer periods. It gave a chance for London to seep back under my skin and in turn brought the London phase of my practice to the surface of my mind. I had thought of it as quite distinct from my Dublin practice and having it resurface was not entirely comfortable and perhaps a large part of the mental warfare that accompanied the process. In the end however, I think it initiated the first phase of discovering a continuity between them and how my practice can benefit from engaging their slightly different critical positions. As a result, I am carrying the dialogue between them into the current project and have even dared dip into the London archives.

The other aspect of showing in London was the audience that included colleagues I studied with and others who know my work from ten years ago and in some cases even longer. It was refreshing to the same extent that showing in Dublin was when I first returned, but for opposite reasons. In Dublin I had the opportunity to reinvent my practice while in London I was faced with the history of my practice.

What are you working on at the moment?

I am currently working on a solo show for the Wexford Arts Centre in Ireland. The title is still swinging but today it is below explanation (the clocks stop at 3pm and existence continues). It is the result of having received the Emerging Visual Artist Award. It is the second project looking at references made by Vivian Sobchack as I consider her somewhat optimistic paper on inter-objectivity. On this occasion the work is developing alongside a close reading of Sartre's novel Nausea, which it seems is generally kept in a box with other adolescent embarrassments. It’s fascinating to read in light of current misanthropic trends. It came before his commitment to humanism and is pervaded by an anxiety of recognising the contingency of existence, of nature invading culture and an attempt to understand the blackness of matter irrespective of its apparent colour. It is also a visual feast, unsurprisingly due to it having passed through a mescaline fuelled body that conjured crabs as imaginary friends to keep loneliness at bay.

For the closing I will again work with Lee Welch to produce a performance. It will develop out from thigmotropism that was performed for the closing of return to the borderland bends. There is an interesting form emerging by which Lee seems to be the body and I the voice of a character contained by materiality yet slipping between categories.

I will also be partaking in a show DEAD ZOO: Becoming Animal curated by Hilary Murray. I am very excited about this show and was delighted to be invited to participate as it touches on issues distinctly present in the current work but which I have yet to thoroughly attend to.

After that I will be making a second attempt at Stalking an Ungrounded Earth. The last of which became rogue occupation. I am currently praying to the core of the earth and the outer cosmos to get funding for this project.

Interview with Ruth Proctor

Her show Falling or Jumping was at John Jones Project Space 8 October – 8 November 2014. She is the artist in residence at John Jones.

How has your experience of the residency at John Jones been so far?

The experience so far has been great and very useful for me, I think the most important reason being that I've had the opportunity to work closely with Cassandra in an ongoing conversation about my practice and in developing ideas for the end of residency exhibition. This has been important in allowing me to look back on work I have made and giving rise to where my work could go in the future.

Could you tell me about your film Falling or Jumping (2012) currently being shown at John Jones Project Space?

This film was made early in 2012, it's a black and white 16mm silent film shot on one roll of film. The film plays with the idea of memory and of physicality, a figure on a white ground comes in and out of the frame repeating the same movement over and over, a figure skater, sometimes falling, sometimes staying upright. Almost like when travelling though fog or clouds the gravitational space of the screen becomes as unstable and unsure as the figure within it. The figure skating is myself. When I was younger I trained as a figure skater and so in this film I revisit this past life by trying to do a simple jump learnt as a child, testing my muscle memory and awareness in space.

What other outcomes are there to your residency?

The main outcome of my residency is an exhibition in the project space which opens in January 2015, this will be a culmination of ideas that I have been working on during the time at John Jones but also looking retrospectively at my work over the past few years which hasn't necessarily been seen. One thing that has come out of my conversations with Cassandra is the idea of presentness and so this will be one of the themes within the show.

Interview with Ludovica Gioscia

Her exhibition Neurotic Seduction Astral Production is at John Jones Project Space

21 November – 20 December 2014

Could you give us a sneak preview of what to expect from your show at John Jones Project Space in late November?

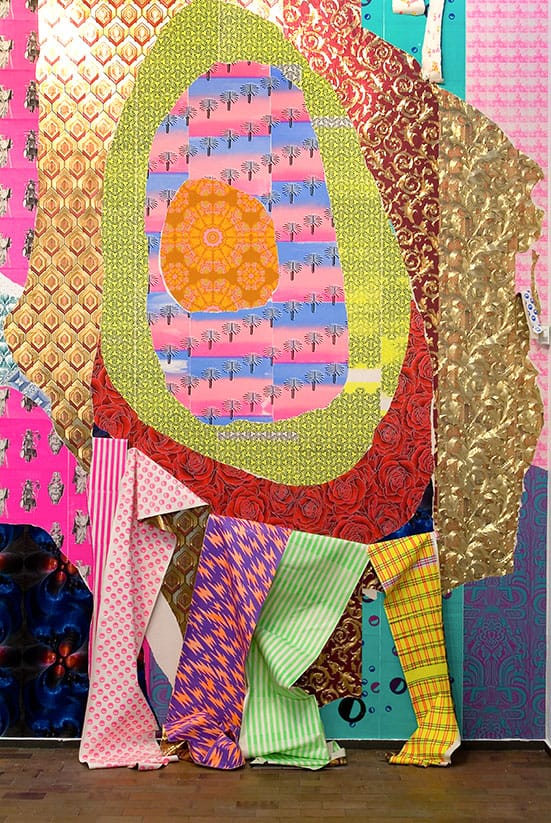

Neurotic Seduction Astral Production is a new work that belongs to the Giant Decollage series. These works are large-scale architectural interventions where layers of wallpapers are stratified and then torn back down, to reveal the patterns underneath. Most wallpapers I design and screenprint, whilst others I buy on eBay or collect around the world during my travels.

New motifs are introduced in my wallpaper archive with every new Giant Decollage. For Neurotic Seduction Astral Production I have developed new motifs that look at our relationship with brands, in particular those connected to technology. The production and installation process behind these large scale works are part of the conceptual framework of the series, by emulating, for example, some of the psychological mechanisms present within our interactions with social media.

Endless hours of printing are required to produce the wallpapers, which are then painstakingly installed one on top of the other to then get ripped down. The obsessive and compulsive construct of the works emulates the obsessive and compulsive instinct that is so predominant in our evolving relationship with technology. Our neural pathways are being rewired by applications like Facebook, as we develop an addiction for the dopamine that our brains produce every time we receive a ‘like’, which in turn leads to the constant reflex to check our homepage.

New patterns for the installation at John Jones include images of expanding brains, labyrinths, dopamine and emoticon precursors, such as Bruno Munari’s drawings of variations on the theme of the human face.

You’ve been very busy recently, how does this exhibition fit into your recent research processes?

The Giant Decollage series feeds off whatever I am researching at the time. Lately I have been collecting Apple packaging and different types of detritus. You can see some examples of new sculptures made with the above materials at 84 Hatton Garden, where until the 22 of November I am part of a group show called Material Girls and their Muses. The show features a new sculpture from the Vomitorium Label, VL fall/winter 2014, which is the result of a fictional collaboration between the label and Apple. The elements that make up the sculpture have been finished in the classic white, grey and black that has become synonymous with Apple as a brand. On one of the elements you can find an iPhone box filled with resin and dirt.

Other Apple packaging is scattered around the show, also containing resin, various debris (including bits of plastic weathered by the sun, sea and wind collected on beaches) and once again dirt. The show also includes new wallpapers, one of which depicts an Apple logo motif encrusted with ash collected from burnt packaging. By inserting the abject I am interfering with the brands’ identity and offering a more holistic portrait of its production line.

In a separate article: Interview with Karl Ingar Røys after his exhibition Burmese Days at John Jones Project Space, 15 August – 27 September 2014.

In a separate article: Interview with Lydia Ourahmane who premiered her performance The Third Choir Archives at John Jones Project Space on 4 October as part of Djazaïr, curated by Ali MacGilp and Yasmina Reggad as part of aria (artist residency in Algiers)’s programme of exhibitions.

Teresa Gillespie

return to the borderland bends (2014)

Installation view John Jones Project Space

Teresa Gillespie

return to the borderland bends (2014)

Installation view John Jones Project Space

Teresa Gillespie

return to the borderland bends (2014)

Installation view John Jones Project Space

Teresa Gillespie

return to the borderland bends (2014)

Installation view John Jones Project Space

Teresa Gillespie

return to the borderland bends (2014)

Installation view John Jones Project Space

Teresa Gillespie

return to the borderland bends (2014)

Installation view John Jones Project Space

with Lee Welch

Ruth Proctor

If The Sky Falls

2012

Performance, Whitechapel Open

Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London

Ruth Proctor

Falling or Jumping

2012

Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London

Ludovica Gioscia

Bomarzo Vertigo, 2010, Fundacio Miro, Barcelona

Found and custom printed wallpapers, 10 by 10 metres.

Photography by Pere Pratdesaba

Courtesy Riccardo Crespi, Milan

Ludovica Gioscia

Bomarzo Vertigo, 2010, Fundacio Miro, Barcelona

Found and custom printed wallpapers, 10 by 10 metres.

Photography by Pere Pratdesaba

Courtesy Riccardo Crespi, Milan

Detail

Ludovica Gioscia

Appetite For Great Design, 2014 (in the background Cloud Ash Dolphin Crash, 2014)

93 x 60 x 99 cm

Resin, ash, dirt, plastic debris, metal, plaster, Ikea table legs, Ipad box, terracotta, make-up, paper and acrylic paint

Courtesy Riccardo Crespi, Milan

At Marcelle Joseph Projects Material Girls and their Muses

Ludovica Gioscia

From left to right: Amarklor Peritonitis, Hooloovoo, Sumatra Samphire and Infra-white, 2014 (in the background Cloud Ash Dolphin Crash, 2014)

Dimensions variable

Packaging debris, resin, ash, plastic debris, plaster, make-up, paper, textiles, plastic, acrylic paint and dirt

Courtesy Riccardo Crespi, Milan

At Marcelle Joseph Projects Material Girls and their Muses

Ludovica Gioscia

Overview of installation at Marcelle Joseph Projects Material Girls and their Muses 2014

Ludovica Gioscia

VL fall/winter 2014 (detail), 2014

Dimensions variable

Resin, dirt, iPhone box, mdf, gloss paint, magnets, make-up sponge and silver pigment.

Courtesy Riccardo Crespi, Milan

At Marcelle Joseph Projects Material Girls and their Muses