What is your background and experience as a curator?

I started to make exhibitions when I was a second year student in the Art History department of the Estonian Academy of Arts. It was in 2000. Since then I have been most fascinated by exhibition making, I guess I have realised more than sixty shows of contemporary art, mostly as a freelance curator. I started as every other young curator probably does, displaying the works of fellow art students and young artists of my generation. I guess it’s a very fruitful combination, having the Art History department in the Art Academy, it enables lots of contact between artists and art historians; it also facilitates co-projects, artist-friends, studying Art History next to people who produce art. I also took Curatorial Studies at De Appel Centre for Contemporary Art in 2004-2005, which was one of the few places at the time where it was possible to get a curatorial education. This was a very valuable experience. It was extremely difficult and tough for me at the time, but it was also the best experience I have ever had, I learned so much from my colleagues who did the programme at the same time.

How long have you been director of Tartu Art Museum?

Could you tell me about the history of the institution?

I started my job on 1 April 2013, so its about one and a half years by now, I have the same amount of time still to go. I have a three-year contract. To describe the institution, I would say it’s a small and provincial art museum at the very end of Eastern Europe. The museum was founded in 1940 by local artists, just a few months after the Soviet occupation. They donated their best works, about 200 all together, as a kick-start for the museum. Despite the war, the state recognised the museum, so it is one of the two state art museums in Estonia. We have a collection of mostly Estonian art, about 23,000 artworks plus the photography archive, plus about 14,000 works deposited in the museum. It’s quite a lot to take care of on a daily basis. The problematic issue about the museum is, that it hasn’t received any major investment, the collection is still in the building the museum moved into in 1946. This singular condition is critical and there is no political will for investments, so its very tricky and dangerous situation we are in at the moment.

What challenges have you faced there?

My task was to re-structure the institution and turn a rather conservative, quiet, peaceful and provincial museum, that mostly focuses on art history, into something more contemporary, vibrant and open. Sounds pretty simple, but it ended up as a conflict on civilisations. It has been a very tough time, the whole process of re-structuring and changing the logic of the programme, as well as ways of communicating. If you could be more precise in the question, I could answer further.

What changes have you made to the museum’s programming?

First of all, curators were hired. Before the exhibition-making process was organised as in Soviet times – each collection keeper had a chance to make a show plus a few thematic shows were organised. One of the main principles for organising a solo retrospective was around the birthday of the artist, such as on their 100-year anniversary for example. Now we focus more on living, emerging artists, and collection shows have to be connected to present day issues. We also have a series of archival exhibitions and guest-curated group shows. There has been a tradition in the museum of exhibiting art from neighboring countries, also once a year in spring we give our space for a week or two to the local university’s Painting Department graduation show.

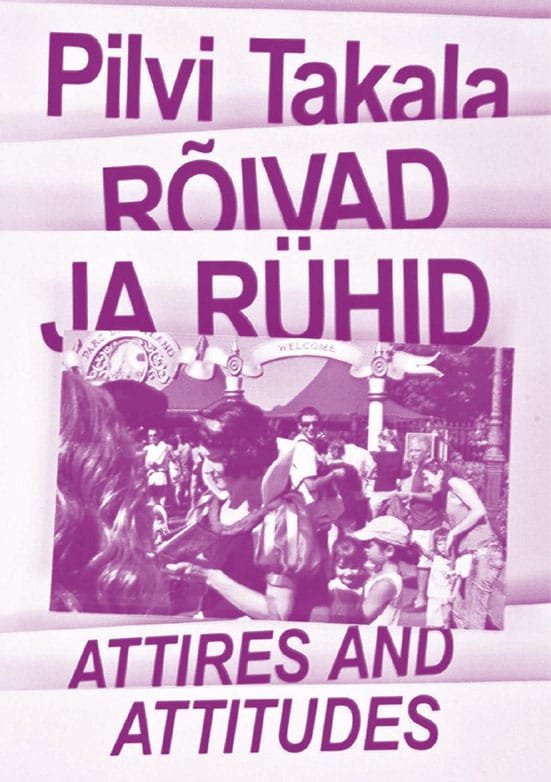

Your current exhibition is a solo show by Finnish artist Pilvi Takala.

Many years ago you showed this artist in your project space in Pärnu. How did it feel to work with her again in this context?

RA: Really very good and comfortable! Pilvi is a very interesting artist, her primary creative method is performative interventions into everyday rituals among different communities and through them experimental research into public space and prevailing social attitudes. I would say it is very different from what we think about performance art in Estonia. She does not produce conceptual objects nor does she objectify concepts, her artistic practice is practice in its most direct sense – it is consistent, continuous and based on carefully planned activities. It is often simultaneously an action and a state of being that is presented in art spaces through edited and post-produced documentation. Each of her new works pushes the limits of her practice further, testing different strategies, and solving more and more complex situations. Pilvi often positions herself in the midst of experiments. Sometimes a seemingly trivial gesture leads to a conflict situation or confrontation, sometimes it gives an exciting inside view into a community’s attitudes and behavioural patterns. It makes sense to show her work as her intervening gestures are generally carefully staged-managed events, plus includes documentation which we experience in the exhibition.

What are your plans for the future programme of Tartu Art Museum?

Our annual programme for 2015 has just been confirmed, as highlights I would mention several shows that we are preparing right now. My young colleagues in the museum who have just started their job this year, they are co-curating a show together with the working title Youth Mode to position themselves in the museum and in the art world. I am curious about what it is going to be. So let’s see, but I guess it might be a generational statement. In summer we have a solo show by Estonian painter Tõnis Saadoja, who has recently realised very strong conceptual site-specific projects that deal with painting. In autumn we will have an extensive solo show of Tartu-based multichannel artist Kiwa, who has been active on the art scene since he was sixteen. Now a major solo show, I guess it will be something experimental. Also as a museum we deal with history. This year we celebrate twenty years of the first Saaremaa Biennale, the first encounter with contemporary art for Estonian audiences, so we have commissioned a show on developments in photography and contemporary art in Estonia. Seventy years will have passed since the end of the Second World War, which we would like to draw attention to. As 2015 will be a jubilee year for Tartu Art Museum, I will continue my institutional critique series with an anniversary show about the new building – something that everyone talks about but has never been built. Let’s see.

Could you tell me about your book project Explosion in Pärnu?

Ou, it’s a long story … Basically the book documents a creative explosion that took place in Pärnu, the fourth biggest town on the west coast of Estonia in the second half of the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s. An era of transformation, the 1990s was a very crazy time everywhere in Eastern Europe, people were very optimistic and sometimes too optimistic. One guy started an art school in Pärnu, in 1998 it ended up in bankruptcy and art students and artists-professors took it over and created something very unique. It was called Academia Non Grata and it focused on collective, durational, body-challenging performances.

A few years ago Kumu Art museum in Tallinn commissioned a show from me about the art scene in Pärnu and somehow it was like time-travelling back to my teenage years. I went to high school next to the art school, so I happened to follow the scene when I was still a high school student. The commission was a great opportunity to go back in time and research the 1990s, which is, I guess, my favorite period of art history. I have been dealing with many topics and issues in my work, but now I found a super interesting subject right in my backyard. I tried to reconstruct the whole revolutionary situation and collect as much documentation as possible. It was like investigating a crime, collecting documentation and mapping links between subjects and suspects. So, the book is about the explosion. It will be out soon, in Estonian and English.

How would you describe the Estonian art scene these days?

It is very difficult to say something in general. Estonia is a small country so the art scene is also pretty tiny, but still there are diverse practices going on. If I were to describe the art practice, I would say that at the moment there is quite a lot of experimentation with painting. There is a new generation of painters, around 25-35 years of age who are willing to experiment, they are not afraid of colour, they are curious about the installation potential of painting, they like playing with it. I think this tendency is somehow very present and manifests itself clearly. There is also a group of artists dealing with gender and queer issues in one way or another. In my opinion this is very interesting, what they are doing, both in the form of white cube exhibitions as well as more activist and theory-based initiatives. At the same time the institutional side of the art scene is in crisis I would say. The Art Academy in Tallinn is about to disappear. The academy failed to build a new building a few years ago, it is split up in many locations around Tallinn. The situation is not very promising, huge damage is being done to art education and the art scene in a wider sense. The young and energetic institution the Contemporary Art Museum of Estonia that started maybe seven years ago as a squat is facing difficulties, it is a typical case of gentrification – artists and hippies clean up the neighborhood and initiate something cool, and then real-estate developers just come and take it … Also Tartu Art Museum’s situation is not the best when it comes to the buildings and deposit spaces. It has become clear that if no one invests any resources into the infrastructure for decades but only distributes small grants for artists to survive, the system or scene as a whole will collapse at some point...

Ali MacGilp

Tartu Art Museum, Estonia

Pilvi Takala ‘Attitudes and Attires’ at Tartu Art Museum

Tartu Art Museum bookstore with Dan Perjovschi drawing