I wasn't quite sure what I would make of the 11th Istanbul Biennial, or its curiously monikered curatorial collective What, How and for Whom (WHW). Its title, 'What Keeps Mankind Alive?', didn't inspire much confidence, calling to mind the lofty meta-conceits that have become both characteristic and cliché of the international biennial circuit. By encompassing vaguely everything yet addressing precisely nothing, I feared it would offer little more than a reprise of its 2007 predecessor; Hou Hanru's hullabaloo of contesting thoughts, gestures and ideas, which oscillated thinly around notions of 'Optimism in the Age of Global War'. However to my profound relief, WHW's tightly curated, mercifully contained meditations on the role of political activism within contemporary practice provided a coherent framework in which to approach a range of work by artists from well off the tried and tested biennial track.

The title, lifted from a song in Bertolt Brecht's The Threepenny Opera, functions less like a theme than a statement of intent. WHW have selected works which can be read explicitly in terms of Brecht's methods and teachings; namely a belief in the open political engagement of art and the power of its potential in transforming society. This could be read as the modus operandi for the Croatian four woman collective themselves, the questions from which they derive their name, What, How and for Whom?, referring to the three basic tenets of economic production that also underpin the conception, planning and realisation of exhibitions. These uncompromising ideals of transparency and rigour pervade every element of their immaculately researched presentation, proudly signalled by the statistical breakdown of the biennial's budget and its contents writ large throughout its three venues and catalogue.

An inverted world-map, daubed in red, greets visitors at the entrance of the main biennial venue of Antrepo no. 3, informing them that only 28% of the 70 exhibiting artists hail from the West, its curatorial emphasis unapologetically weighted with the 'Rest'. Predominantly focusing on Eastern Europe and the Middle East, WHW's polemic treatise acquires additional pertinence and is deliberately problematised by focusing on political regimes in which artistic expression has been openly instrumentalised or suppressed.

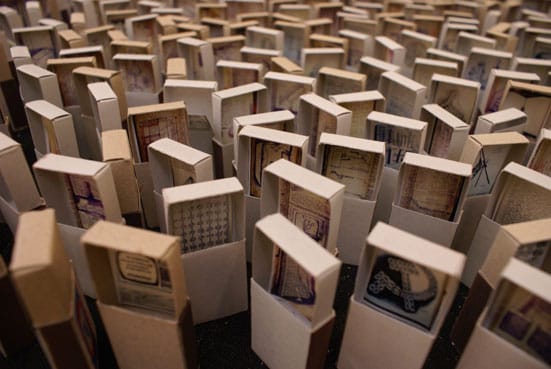

Works range from the multi-layered and nuanced to the downright didactic. A clumsy case in point of the latter is Sanja Iveković's Turkish Report (2009), an intervention of angrily crumpled crimson papers littered, confetti-like, throughout each venue. The pages, from a women's NGO report about the prevalence of honour killings in Turkey, are discarded, downtrodden and stomped upon, in an excruciatingly literal manner. More subtle yet equally indicting are Hrair Sarkissian's photographs of seemingly innocuous leafy plazas in Syria, which reveal themselves to be Execution Squares (2008)- central spaces where the capital punishment of civil criminals are publically undertaken. The lifetime hoardings of Vyacheslav Akhunov – collages, matchbox sculptures and diaries, which presumably remained closeted and hidden until the fall of communism in his native Tashkent - assume a more ambivalent position. The rhythmic persistence of works such as such as Leninana (1977-82), an obsessive collection of Soviet propaganda, reiterated throughout the venues with repressive regularity, creates a quasi-claustrophobic aura of bombardment and an unspoken evocation of the misuses of art with a political bent.

There is perhaps unsurprisingly a strong reliance on video and documentary formats, much of which provided the most powerful content of the biennial. Igor Grubić's diptych East Side Story (2006-8), presented in the basement of the disused Feriköy Greek School, showed on one screen a brutal archive of documentary footage of attacks against the first Gay Pride celebrations in Belgrade and Zagreb in 2001 and 2002. This was counterpoised by an interpretation of the events, translated through contemporary dance, in the spaces that the attacks occurred in. Unwatchable aggression syncopated with restorative balm, the work makes an argument for the redemptive properties of art, its power to educate coupled with pedagogic setting.

There are criticisms of the exhibition that detractors, immune to the charm of WHW's particular brand of ‘Turn Left!' romantic socialism, have rightly pointed out. Heavily text-dependent and measured to the point of monotony, there are very few instances of visual relief. Hans Peter Feldman's Bread (2008) and Oraib Toukan's video installation The Equity is in the Circle (2007-9) provide rare examples of levity; the latter imagining a scenario in which nation states are auctioned off under 100-year lease. Consulting real life experts including an estate agent (‘well, you could take a punt on Jordan’), a brander (‘Iran has a real image problem’) and a diplomatic strategist amongst others, he takes their advice and the projected GDP of each nation as the jumping off point for a fictional enterprise, Nayruz Holdings.

Others, more familiar with WHW's previous projects, might label their presentation formulaic and predictable, as a most cursory google will attest, having worked with many of the artists in exhibitions with not dissimilar premises before. However for me, it was an eye opening and uplifting experience, exposing me to a host of sophisticated practitioners viewed through a prism, albeit crimson tinted, sympathetic to both work and context. Clutching my standard issue moleskin filled with a dozen or so oddly accented names I will never be able to spell or pronounce, I left with a hunger to see more and a renewed faith in what a biennial can and should be.

Shamita Sharmacharja

Igor Grubić, "East Side Story”

Courtesy of the artist

Vyacheslav Akhunov, “1 m2”, 2007

Courtesy of the artist

Hrair Sarkissian, “Execution Squares”, 2008

Courtesy of Kalfayan Galleries, Athens – Thessaloniki