The title of Daniel Birnbaum's Venice Biennale is Making Worlds. His point of departure is a simple one: art embodies a vision of the world and if taken seriously must be seen as a way of making a world. The world-making process is further complicated by artistic and cultural translations and productive misreadings, underlined, somewhat platitudinously, by the multiple translations of the title on the catalogue cover. The main exhibition is less clamorous than previous editions, but provides low-key enjoyment in a year when many national pavilions failed to excite, displaying what we have seen before (USA), what we couldn't see because we didn't get out of bed early enough to book a precious seat (Great Britain), sombre non-events (France) or the downright dull (Spain).

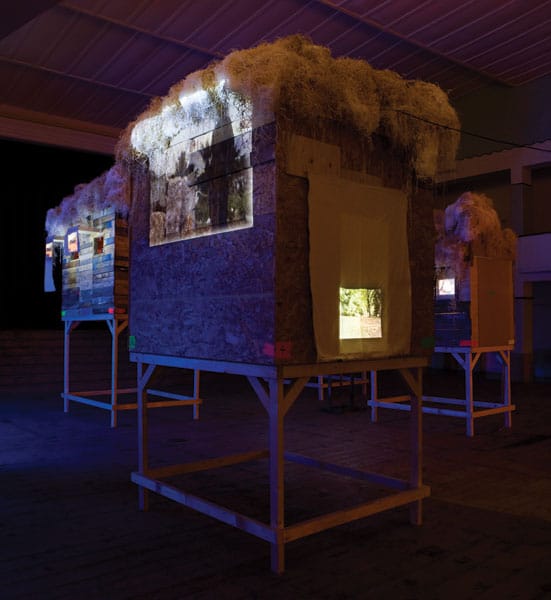

Almost any artist's practice could be subsumed by Birnbaum's open-ended curatorial premise, nevertheless, it is possibly to draw out some characteristics of this exhibition that stretches across the vast ex-Navy factory of the Arsenale and the main, Italian pavilion at the Giardini. The pace of the display is notable: the Biennale exhibition seems less exhausting than usual, the works are given space to breathe. The entrance to the Arsenale is usually where curators set the tone of their exhibition – a space occupied by Ron Mueck's giant Untitled (Boy) in 2001 and where the Guerrilla Girls ushered in the so-called ‘feminist Biennale' in 2005. Here, Birnbaum has selected to locate Lygia Pape's Ttéia (2002) where her floor to ceiling gold threads glide through the hushed, darkened space like magical sunrays into a dim cave. The work is subtle and sensitive, alluding to the nature of the curatorial vision that underpins the exhibition. Having said that, in the next room, Michelangelo Pistoletto's smashed mirrors become almost an assault on the senses, as viewers with dilated pupils are propelled into a painfully, bright, reflective space. Such visual extremes are followed by the multi-sensory bombardment of Pascale Marthine Tayou's installation, which uses shantytown bric-a-brac and disparate urban noises to create an audio-visual cacophony. Movement from one room to the next sees a shift in mood, pace and sensation. In the Main pavilion, the attention – verging on obsession – to detail is a hallmark of the more memorable works including the bizarre eroticism of Nathalie Djurberg's Claymation films set in a sumptuous, ceramic jungle and Hans Petter Feldman's spotlit hoarded knick-knacks, set on turntables and casting ominous shadows on the wall.

A great deal of consideration has seemingly gone into the viewer's experience of the Biennale. The education section and play area, designed by Massimo Bartolini, has been given a prominent space near the entrance to the main pavilion. Rirkrit Tiravanija has conceived the library and the reading room, and Tobias Rehnberger has decorated the café. Some of the works encourage audience interaction such as Anawana Haloba's ‘global brand' tins with sweets, Alexandra Mir's Postcards From Venice or Yoko Ono's Sun Piece. There is also a great deal of humour at play in many of the works, with Bestué/Vives wonderfully silly videos proving a crowd pleaser. The Biennale's wall texts and catalogue are sympathetically low on artspeak and theory waffle; the image is paramount, text a mere helping hand, making this a pleasantly accessible display. The selection of artists also appears to be diverse and open: the artists range from youngsters, barely in their 30s (Keren Cytter, Nikhil Chopra, Anya Zholud) to renowned veterans (John Baldessari, Joan Jonas, Yona Friedman) to the long dead (Öivind Fahlström, Gordon Matta-Clark, Palermo). There appears to be a near gender balance, and it is evident that Birnbaum has sought to embrace globalism in terms of the geographic origins of the artists included, albeit mainly with practitioners who are already well-known names on the international biennial and exhibition circuit.

The historiography of 20th century art and architecture provides fodder for a number of artists in this year's Biennale. Referencing, appropriating and adapting historical movements has long been a feature of Sherrie Levine's work, and she is included in the Biennale with Melt Down (After Yves Klein). Twentieth century European modernism provides a backdrop for many other works: Falke Pisano's visual language is steeped in references to modernist abstraction; Ulla von Branderburg sets her film Singspiel against the scenery of Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye; Simon Starling's brilliant, cyclical installation Wilhelm Noack oHG, where his kinetic sculpture serves as the reel for a film that spans the history of the eponymous Berlin metal factory from it inception in 1897, highlights its role in relation to both the Bauhaus and the Third Reich. Pavel Pepperstein, on the other hand, uses the early Constructivist approaches to create his watercolour visions of Landscapes for the Future. Pop Art is another plundered genre, as evidenced in the works of Rachel Harrison, Guyton/Walker and Jan Håfström, among others. Actual works from earlier periods also feature, including recreations of Gutai's performance props and Tony Conrad's Yellow Movie works from the early 1970s; André Cadere's omnipresent circular, multi-coloured poles underline the historical precedents and linkages of this contemporary display. Birnbaum himself references Pontus Hultén and Harold Szeemann in his catalogue essay, locating his own approach within the trajectory of the nascent history of curating.

Of the national pavilions dotted around the Giardini and across the city of Venice there were a few highlights. The Nordic pavilion, which, along with the Danish, hosts Dragset and Elmgreen's curatorial venture, is the most distinctive (and had the longest queues), as audiences are taken round the two homes created by the artist duo by an effusive estate agent. Pretty houseboys, in various stages of undress, lounge around the house created from Sverre Fehn's distinctive 1962 pavilion. The works of artists in the show, including a number of younger Scandinavian artists, were overshadowed somewhat of the imposing camp aesthetic of D&E's curatorial vision, but the whole venture injected some sorely needed playfulness into the overall grandeur of the Biennale's national displays. Other Giardini highlights include Fiona Tan at the Dutch pavilion, whose Disorient included video-installations with voiceover readings from Marco Polo's travels, underscoring the importance of Venice in the historical relations between East and West; Roman Ondak's wonderfully succinct, outside-in gesture for the Czech and Slovakian collaborative venture; and Lucas Samaras's beguiling tableaux vivants portraits in the Greek pavilion.

Across the city, Theresa Margolles delivers another gut-wrenching reference to violence in her native Mexico, displaying bloodstained cloths used to wrap dead bodies. Blood also features in a performance work, where the floor is cleaned with water used to clean the victims of organised crime. Margolles's unapologetic use of pathos teeters on the edge of maudlin sentimentality, but manages to appear poignant. Across the bridge, Mona Hatoum's intervention in the collection of the 16th century Palazzo Querini Stampalia provides an engaging treasure hunt for her miniature works among the historical relics. The Welsh Pavilion out at the Guidecca is worth the trek, though the five-screen video installation is something you are subjected to rather than something you look at, interspersed with harrowing images of the artist being waterboarded. The Estonian pavilion houses Kristina Norman's multi-media work After-War, which examines the backlash following the removal of the so-called Bronze Soldier from Tallinn. Her close-up documentary footage of the riots by the Russian minority population of the city is a fascinating testament to group dynamics and violence in general, as well as the specific socio-historical context of Estonia. Artsway's New Forest Pavilion was my own favourite, in particular Nathanial Mellor's absurdist narrative video with its temporal twists and semantic deformities and Jordan Baseman's film Nasty Piece of Stuff, where the narrator's tone dictates the speed of the images that flash across the screen, mainly as abstract blurs, but occasionally pausing to allow us to decipher their scenographic clues.

It comes as no surprise that the few new discoveries in Venice are found among the collateral events, for this grand old dame of the biennale circuit is very much a stage for the establishment. Even the ‘youngest ever' curator of the oldest art biennial in the world couldn't change that.

Natalie Hope O'Donnell

Lygia Pape

TTÉIA 1, C

(2002) 2005

Gold thread in square forms

Project Lygia Pape - Cultural Association

Photos : Paula Pape

Nathalie Djurberg

Experimentet (detail)

2009

Installation, clay animation, digital video and mixed media, dimensions variable

Music by Hans Berg

© Nathalie Djurberg

Courtesy: Giò Marconi, Milan, Zach Feuer Gallery, New York

“The Collectors”

The Danish Pavilion and The Nordic Pavilion

53rd International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia, 2009

Czech Republic and Slovak Republic Pavilion

Roman Ondák

Loop

2009

Preliminary site photographs for installation in the Czech and Slovak pavilion

Courtesy: gb agency, Paris, Janda Gallery, Vienna, and Johnen Gallery, Berlin

Pascale Marthine Tayou

Human Being

2007

Mixed media, dimensions variable

Photo: Ela Bialkowska

Courtesy: Galleria Continua, San Gimignano / Beijing / Le Moulin