On entering the grand former Bank of Norway, home to the Museum of Contemporary Art, visitors are met with a red carpet, rolled out by Cuban artist Wilfredo Prieto, running the length of the entrance hall and up the stately staircase. Small lumps appear under the thick fabric; something has been swept under the carpet. The curators, Koyo Kouoh and Stina Högkvist, have selected the theme of ‘hypocrisy’ for their exhibition that forms part of the 2009 ‘Africa in Oslo’ project. The title refers to the site-specificity of moral codes, which appear to lose their hold when we travel beyond our local contexts. Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness provides an historical example, while the African ventures of Norwegian oil companies reflects a current exploitative tendency among many multinational corporations. As the catalogue commentary points out, European morality that preaches human rights, tolerance, democracy, workers’ rights etc. does not necessarily apply when global economic competitiveness is at stake.

Steve McQueen’s large-scale projection, Gravesend, which viewers may have seen in the 2007 Venice Biennale, reminds us that not much has really changed in Congo since Conrad’s day. Coltan, essential to the production of mobile telephones, laptops and DVD players, has replaced ivory as the bounty of Western exploitation. A deafening soundtrack composed of the ambient noise of workers hacking away at rocks to extract the mineral accompanies close-up footage of taut, sweaty bodies, swollen hands, and the deep red, glistening earth. The camera’s zoom captures the intensity of the process while denying us the pan out that would identify any of the workers. This intense manual labour is crosscut with footage from the high-tech, mechanised process where the coltan is refined. An animation suddenly interrupts the documentary style of the film, and a thin black line meanders across the screen, which corresponds to the River Congo. Conrad’s narrator, recounting his story aboard a yawl moored at Gravesend, tells of how he sailed up the river in pursuit of Kurtz, the rogue ivory dealer. Kurtz’s advancement along the snaking waterway – into the heart of darkness – became emblematic of his gradual moral demise.

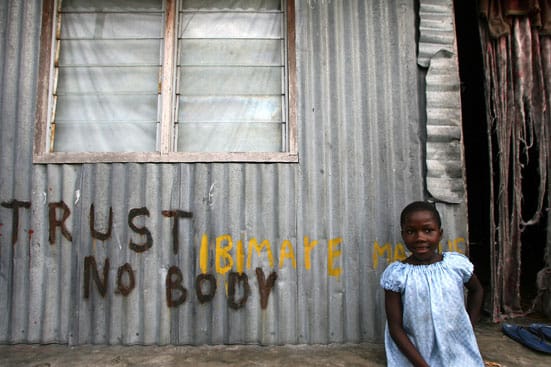

The pursuit of oil is central to George Osodi’s work in this exhibition. Having witnessed Norwegian oil exploits in his native Nigeria, Osodi continued his investigation into the same company’s ventures in Norway. His two-screen slide show juxtaposes photographs from the Niger delta with documentary images he shot on residencies in Norway. Both slideshows feature cropped images that underline the hurried, photojournalistic aesthetic of the work. In both storylines, the relative ripple effects of the oil exploits (high-rise buildings for the Norwegians, none for their Nigerian counter-parts) are broken by stunning landscape scenes, where the hazy African orange-red hues contrast with the sharp blue of the Nordic winter light. In both countries, the victims of the frantic scramble for this finite resource are shown, whether they are inhabitants of the African delta whose houses have burnt down, or North Sea divers, incapacitated following their work on the initial oil discoveries on the Norwegian continental shelf.

Interconnectedness is a prominent feature of this exhibition. Rather than present a conventional show of African art in Oslo, the curators have opted for a more hybrid approach, reflecting the diversity of a now global art world. The cavernous Bank Hall is dominated by the multinational artists’ collective El Parche, whose wooden pallets, stuffed with old clothes, create a centrepiece and a platform for their discussions around globalisation’s ‘collapsing utopias’. The accompanying collaged fanzine underlines the soapbox aesthetic of their work. Georges Adéagbo’s installation, covering the walls and floor of his space, is comprised of assorted bric-a-brac gathered from Norwegian flea markets alongside equally diverse materials from his native Benin. His neatly placed hoardings echo traditional cabinets of curiosity. Other artists employ contemporary global advertising imagery. Multinational companies are present in many of the works, whether it is Pascale Marthine Tayou’s wall of logos that scatter the Cameroonian visual landscape, or Gunilla Klingberg’s intricate wall pattern, where closer inspection reveals it to be made up of the emblems of large international supermarkets, such as Spar and Lidl.

Bashing big corporations has been in vogue for some time. When selecting a thematic such as hypocrisy, particularly in an Oslo-Africa context, there is always the risk of excessive moralising and earnestness. This exhibition teeters on the edge of such rhetoric, but successfully manages to circumvent any singular reading of its curatorial premise. Olaf Breuning’s work is integral in this regard by inserting the elements of humour and irony. His narrator in the mockumentary Home 2 is toe-curlingly funny, with his tall skinny frame, topped with a foppish mane of bright red hair and freakishly white-blue eyes, trying to be ‘down’ with the locals, breaking his mobile phone with mock poignancy and serving up platitudes about the wonders of travelling as a ‘global citizen’. This buffoon ambles around the world – to Switzerland, Papua New Guinea, Japan, Ghana, New York – generally offending or bemusing everyone along the way, including his fellow travellers, whom he scathingly dismisses as mere tourists. The continued exploitation the African continent, which several of the works allude to, is an embarrassment to many Western countries, including Norway. Breuning’s work is effective in shifting the chagrin from the amorphous ‘multinational corporation’ onto us as individuals.

21 February -10 May 2009

National Museum of Art Architecture and Design

Museet for Samtidskunst, Bankplassen 4, 0153 Oslo

Natalie Hope O'Donnell

Hypocrisy. The Site Specificity of Morality. "Afrika i Oslo" Photo: George Osodi

Hypocrisy. The Site Specificity of Morality. "Afrika i Oslo" Photo: George Osodi

Hypocrisy. The Site Specificity of Morality. "Afrika i Oslo" Photo: George Osodi