7-27 February 2009

Arresting in its criticality and positing of the most urgent questions surrounding art production and public engagement, the Jakarta Biennale is a much needed respite for jaded art tourists. Its curatorial commitment, as well as sheer production has a stirring potency for multiple audiences. And its strategy to reclaim public spaces and cultural experiences in a city of 23 million people is without a doubt, a formidable self appointed challenge. Mission statements that look at the local, regional and international through the work of artists under 40, and all with a connection to Southeast Asia makes, for once, makes perfect sense as a remit, both conceptually and in its display.

Indonesia, for all its perceived socio-political contradictions has one of the strongest traditions of the arts in the Southeast Asian region. Culture, including contemporary art and curating is taken very seriously indeed, unlike the disjointed efforts of its regional neighbours. Nevertheless this biennale is perhaps one of the lesser known international art events on the UK radar, despite its existence since 1968. The reason for this is context. The first instalment of the biennale then known as the Pameran Besar Seni Lukis (The Grand Exhibition of Painting) reflected its focus on a traditional medium which was specifically Indonesian. Its title then shifted to ‘biennale’ in 1994 but its concentration still centred on local artists. Arena, the 13th edition in 2009, is the first time that selection has been opened up to international artists. However, rather than adopting strategies like the Singapore Biennale whose brash juxtaposing of big international names with local artists to create relationships that were as necessary as another reality tv show, Arena’s curatorial impetus successfully creates dialogue and most importantly allows for new possibilities for contemporary art to emerge in the region.

The Jakarta Arts Council (JAC), the driving force behind the biennale, has organised Arena into three main sections: Zone of Understanding, Battle Zone and Fluid Zone that look at art’s relationship with the urban and issues around its accessibility. Its selection of Ade Darmawan as Programme Director reflects a concerted effort to engage with this theme through the expertise of those in the field. Darmawan, is not only a member of JAC but an artist and director of the well known Jakarta collective and non profit arts space Ruangrupa. Ruangrupa through, research, documentation and exchange constantly engages with this notion of art within an urban context. As such, Darmawan observes the fact that neutral public spaces are diminishing and being more and more dominated by industrial and commercial forces. It is this process that transforms public space into a space for struggle and competition. There is a need therefore, ‘to see the city as an arena to re-recognise, a place where we can devise strategies using spatial innovations and new mechanisms. We envision the city… as an arena rife with possibilities for intervention and re-negotiations among many different interests.’ He also acknowledges that everyone involved in the biennale participants in this realm. Moreover, the challenges the organisational and curatorial team faced in both production and remit, led to a very honest consideration of the chance of failure. This possibility of failure, rather than being an obstacle, is embraced and respected as a useful tool for growth. For a biennale to openly consider its relevancy and how it can not only benefit but activate its public in such a honest and frank way in its texts and press releases is one thing. But would the actual works on display and accompanying programmes fulfil these well considered concepts?

At the time of the opening of the main exhibition sites for Fluid Zone, much of the programme for Zone of Understanding and Battle Zone had already taken place at the end of 2008 and early 2009. In Zone of Understanding various programmes, exhibitions and activities on dance, theatre, film photography and young people’s workshops that looked at Jakarta as a city, were organised to actively engage and interact with the public. A way to provide what the Biennale termed the ‘expansion of visual experience amongst city subjects’ and inform the public on what is going on around them in the sprawling metropolis. Battle Zone curated by Ardi Yunanto consisted of three parts: a public art workshop, billboard workshop and showcase of student works from the best of the Jakarta 32˚, a Biennial exhibition held by Ruangrupa. It examined the notion of space and memory and the possibility of creating new sites of interaction within the city. Happenings, large scale public billboards, exhibitions in luxury shopping malls, murals and performances took over pockets of the city frequented by a vast cross section of Jakarta. Immense in its own scale and infiltration these two zones in themselves created a rich and diverse array of choices to consider how we negotiate cities and our place within them.

Fluid Zone, curated by Agung Hujatnikajennong in was housed in both the National Art Gallery and the uber-up-market shopping complex Grand Indonesia reveal the power of the biennale to create meaningful platforms. Biennales, are meant to be about dialogue between the host city and artists. However, this dialogue often gets lost in presentation and juxtapositions between works seem forced or irrelevant. However, in this instance, the Biennale’s opening up to regional and international artists fused together the notion of the gaze, that is both inward and outward, personal and public, active and passive in relation to Southeast Asia. This gaze takes in a variety of discourses and sentiments from post colonial rumblings, pop culture and urban angst, pastiche and cliché, gender contradictions and social commentary. And the remit of younger artists below 40, included foreign artists who had taken part in residencies in the region with work produced from 2000 onwards seemed to be an attempt to capture the zeitgeist, one could say.

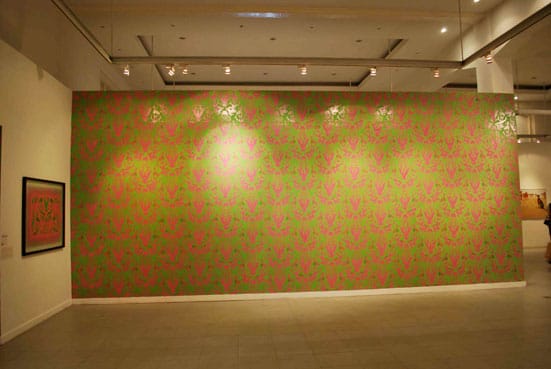

As a result many of the region’s exciting young artists were on display from Victoia Cattoni, Donna Ong, Ming Wong (Singapore), Lyra Garcellano and Poklong Anading (Phillipines), Vincent Leong and Roslisham Ismail aka Ise(Malaysia), Tawatchai Puntusawasdi, Porntaweesak Rimsakul (Thailand) and Videobabes, The Secret Agents, Tintin Wulia, Reza Afisina and Kuswidananto aka Jompet (Indonesia). Revealing how artists in Indonesia and the region see themselves through problems of personal and public identities blend with outside commentaries by artists such as Phil Collins, (UK) Adrià Julià (Spain), Takuro Kotaka (Japan), Sylvain Sailly (France) and David Griggs (Australia). Within this context there seemed to be little exoticisation but more a collective curiosity about the region, its contradictions, successes and failures that infiltrate individual concerns. This commonality of purpose and aesthetic of the Southeast Asian subject, playfully and intensely unites the work rather than divides it.

The sole limitation of the Biennale was that it was not long enough. Three weeks for the exhibitions in Grand Indonesia and the National Gallery provided a necessary tool box to question not only issues surrounding Southeast Asia as a region, what it is, what it isn’t and where it may go but also issues surrounding biennales themselves. Rather than being cloyingly self-referential, viewers are allowed the space to enter into these considerations on their own terms but within a reflective framework laid down by the organisers. In this way Indonesia continues to be light years ahead of its neighbours and it shows. Southeast Asia may not be the (now shaken) art power houses of India and China but if this Biennale proves anything, it is the cultural strength and vibrancy of this complex Asian region.

Eva McGovern

Phil Collins, Dunia Tak Akan Mendengar, 2007

Vincent Leong, Tropical Paradise, 2009