It's hard to know where to start with Cambodia. Ancient or modern? Heritage or politics? Temples or torture? This is a country which holds horror and beauty together in its fragile grasp. Hearing the country's name can only ever evoke two images; that of the Angkor ruins, Cambodia's heart, and the Khmer Rouge, the arrow which shot it through.

Modern art in Cambodia has understandably suffered due to the genocidal regime. The slaughter of artists by the Khmer Rouge, coupled with the near-obliteration of the country's infrastructure during that time, diminished the country's capacity to support new visual arts. Most artists are forced to earn a living through the sale of paintings and sculptures inspired by the temples of Angkor. However, the work of artist Vann Nath breaks with this trend, and performs a crucial function in showing us the extent of the brutality visited upon the population during the Khmer Rouge's reign.

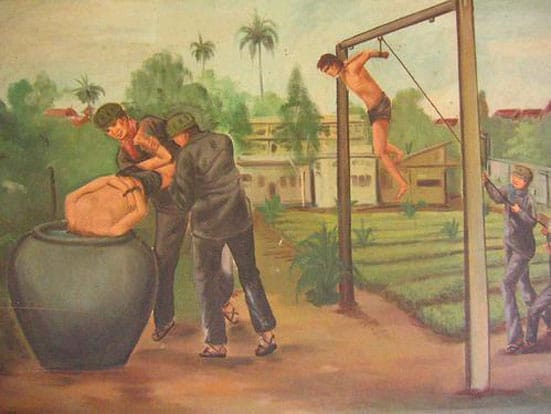

One of only seven people who survived the Khmer Rouge's notorious S-21 (now known as Tuol Sleng) prison in Phnom Penh, Vann Nath recorded the abuses he witnessed in a series of paintings, which have been exhibited around the world and currently reside in the prison, now a genocide museum. Situated in the last building one visits, they detonate the sense of silent dread and residual terror that cling to you and grow as you make your way through the disused cells and torture chambers.

The purpose of these paintings is not aesthetic, but rather to bear witness to the suffering of a nation. The appearance of the work is unpretentious and simple; these pictures are designed to present the facts, and one feels that any attempt to stylise them would undermine their meaning. Vann Nath's paintings are his testimony to the barbarity and inhumanity of the Khmer Rouge, and as such must feel as real as possible. One is awe-struck, as well, by the artist's ability to render so unflinchingly scenes which most would be desperate to forget. Perhaps what's most remarkable is how these artworks stir your faith in the human spirit, at the same time as rupturing your faith in human nature.

Travelling north-west from the capital brings you face-to-face with Cambodia’s ‘other’ history. Angkor’s iconic city of crumbling temples has become the defining representation of the might and decadence of ancient civilisations, the towers of Angkor Wat the most celebrated image. Less renowned, however, are the carvings and bas-reliefs found on the temples’ walls and corridors, often hidden away behind fallen masonry and giant tree roots. These images reveal elements of the lives of the inhabitants of Angkor, as well as depicting the myths and legends they believed in. In a location over-run with secrets and oozing mystery, these sculpted blocks of stone provide answers at the same time as deepening the riddle.

This palpable sense of intrigue is heightened by the look on every carved visage that you see, whether it is a dancing apsara (female spirit), an ordinary farmer, or one of the huge faces staring out from each side of the Bayon temple’s towers. Each expression hinges on the most impenetrable, enigmatic smile. One can only speculate as to what these smirking eyes have witnessed, but behind each inscrutable gaze lies the assertion that it is more than you can possibly imagine or ever find out. The skill involved in capturing this in stone is, of course, staggering. Once again the overwhelming feeling is one of awe, although of an utterly different kind.

And therein lies the magic of Cambodia. It is a land with such spectacular and inspiring art and architecture, products of a wondrous and illustrious history, and yet it is equally characterised by the tragic fault-line of the recent past on which it sits. You are presented with two conflicting sets of stories, each the inspiration for works of art which dazzle and distress in equal measure, depending on their origin. It is an intoxicating combination, which etches one’s experiences in the country into the memory. That, surely, is most important of all, ensuring that a people still contending with such an anguished legacy are heard and thought of around the world.

Natasha Rowland

The Dancing Women from Angkor Wat

Image courtesy of Natasha Rowland

The Bayon Temple in Angkor Thom

Image Courtesy of Natasha Rowland

Vann Nath - 'Water Torture' on display at the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, Phnom Penh