Dear Artvehicle,

On 7 May in Knoxville it has already reached 90 degrees by noon and the

intense midday sun photographs a shadow city under street lamps and

sign posts. Looking down wide streets that shimmer in the heat and that

seem to elongate as I attempt to walk them I have the typical

European's induction into American space. I only manage to reach a

couple of galleries whose addresses I have jotted down but I end up in

Knoxville Museum of Art, an impressive modern museum that is bathed in

a diffused form of the light that is blinding on the street outside.

KMA is currently showing works by Tim Davis from his Permanent

Collection series, an exhibition that brings the effects of light to

the surface.

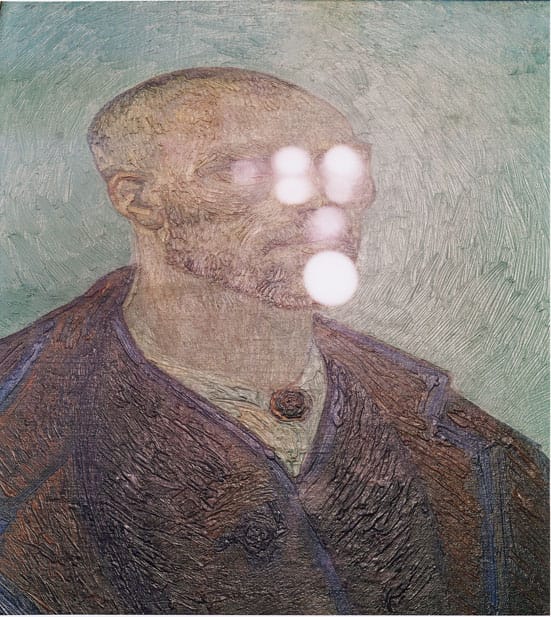

In this recent work the New York artist photographs paintings from the

permanent collections of major art museums. Into these 'reproductions'

of canonical works Davis introduces light as a mediating device which

refocuses our perspective: the intervention of glare and shadow on a

painting or the reflected image of museum surroundings upon glass. The

trick of light is Davis' motif in this series. In Self portrait 2003

which captures a haunting late Van Gogh self-portrait, reflections of

museum spotlights cruelly blank out the shaven-headed Van Gogh's eyes

and mouth. However in Basket of Fruit 2003, a dispersed spattering of

light reveals the weave of canvas and the textures of paint in a way

that conventional photographic reproductions avoid.

The idea that light is a paradoxical force that both illuminates and

blinds is introduced in the exhibition's texts as an analogy for the

museum: at once the home of knowledge and a machine of ideology that

obstructs access to the truth. This is a neat concept and this

exhibition of Davis' work seems slick at first glance (and perhaps flat

like the world in which a sleeping museum guard is grafted onto the

canvas of Joan Miró's Danseuse Espangoles). However once our eyes

become accustomed to the installation that appears like a replica

museum in the dimmed gallery, depths are revealed. Where the mouth of a

saint is erased by a white smear or a Christ is veiled by the

reflection of a curtain, light suddenly seems weighty and the work much

more ambiguous than anything we can reel off about critiquing art

institutions. Davis who describes himself as a 'New Luminist' seems to

aim at something more elusive as he reveals the contradictory

properties of light.

A conservative curatorial decision adds to the ambiguity of

Davis' work and suggests confusion on behalf of KMA. I almost missed it

but hung on the back of a temporary wall at the far end of the gallery

is his L'Origine du Monde 2004. This photograph is introduced by

warnings of 'adult content' and it shows Courbet's famous painting of a

woman's body that centres on the vagina rendered in realist technique.

Courbet's painting has had a controversial life, its previous and most

famous owner was psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan but it now hangs in the

Musée D'Orsay. It seems incredible that its image should invoke

censorship and parental advisory notices in a contemporary art

exhibition but I remember that this is the American South (I have spent

most of my time in a Knoxville where bumper stickers oppose the war in

Iraq and support Obama from president). I start to wonder whether

Courbet's painting is also hidden away in its permanent position in

Paris. Then I remember that we are not anyway talking about Courbet's

painting but Davis' photograph where a patch of light lands just above

the famous vagina. The catalogue essay describes Davis's photographs as

'simulacra' but KMA's decision blurs this distinction and conservative

values trump Baudrillard. I perversely enjoyed this unexpected anomaly,

it seemed to distort the intentions of the exhibition and the sense

that Davis' images have something clear to reveal.

SH