I first met Eric Fong when I participated in his work Chinese Tongue Diagnosis at the Chinese Arts Centre (C.A.C.), Manchester in 2005. I was filmed sticking my tongue out and then given a diagnosis using traditional Chinese method.

This year Fong is back at the C.A.C. presenting a solo show, Seeing Beyond, 23 January – 5 April, which will travel to A.P.T. Gallery, London in July. Fong presents his new work Ways of Seeing: Blindness and Art which investigates how experiencing art can be mediated through the assistive service of audio description, and to examine the gap between visual perception, verbal description and mental interpretation. Fong takes as his point of departure the unsettled relationship between seeing and words articulated by John Berger’s in his seminal text, Ways of Seeing 1972.

In his practice Fong explores the individual’s experience of health, the body, disability, differing medical approaches and wider social attitudes. His work is informed by his former career as a physician. He works in video, sculpture, photography and live art.

AM: How does the visitor to the C.A.C. experience your new work, Ways of Seeing: Blindness and Art, a video installation exploring the perceptual experience of three visually-impaired subjects and a guide dog while visiting an exhibition, accompanied by a professional describer?

EF: This is a 3-screen video projected onto a large wall in the gallery. It opens with footage of a stroll around an exhibition at the Whitworth Gallery from the guide dog’s perspective recorded by a camera attached to it. The professional audio describer then describes in detail one of the works to the visually-impaired subjects, with additional information about the artist provided by comments from the curator. While listening to the audio description, the viewer is watching on one screen, footage of the participants in dialogue with the describer and curator and, on the other screens, digital simulation of the subjects’ visual perceptions of the artwork (limited by the type and extent of their visual impairment), all punctuated by footage of the guide dog’s point of view.

AM: For this work you collaborated with a group of visually impaired people in Manchester. Is social engagement important to your practice?

EF: Yes, social engagement is certainly an important aspect of my practice. For this work, I collaborated with visually-impaired people from the Henshaws Society for Blind People in Manchester. In some of my other projects, I have worked with people with dementia and mental illness, with Chinese medicine practitioners, and with local communities in the U.K. and in Shanghai.

AM: Your work is timely, as issues around ‘access’ are a primary concern for galleries today. Is this an area that interests you?

EF: Yes, it is. Through Ways of Seeing: Blindness and Art, I hope to raise awareness of how an appreciation of art is not restricted by disability and encourage debate as to how the visual arts can be made more accessible to people with disability.

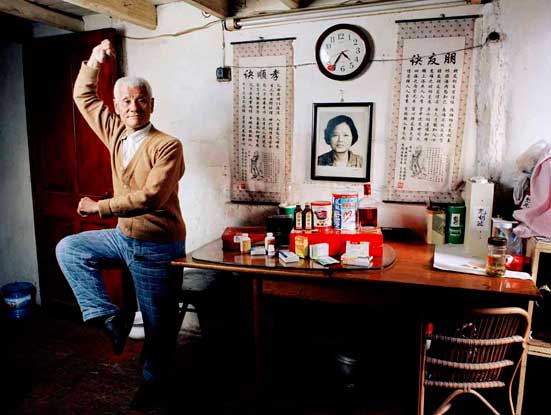

AM: Also presented in the C.A.C. exhibition are Shanghai Remedies: Portraits, in which you photograph subjects surrounded by their collections of medicine. How did you find your subjects? How are attitudes to medicine in China changing today as a result of globalisation? How would you characterise attitudes to health and the body in the U.K. as compared with China?

EF: I found the subjects through various sources during my artist residency in Shanghai – through contacts provided by friends and colleagues in the U.K., the Shanghai British Council, and people I happen to meet on the streets and public parks in Shanghai. I met Mr. Hu, for instance, while I was photographing an old building on a street near my studio. He happened to walk by and started chatting to me because he lived nearby and knew a lot about the history of this building and because he was interested in photography.

It is interesting to observe that while Traditional Chinese Medicine (T.C.M.) has become increasingly popular in the U.K., the reverse seems to be happening in China – there is increasing preference for Western medicine over T.C.M.. This is not surprising in the context of China’s rapid economic growth and Westernisation in recent years. However, as a result of privatisation of medicine, medical companies and health service providers in China employ overt advertising strategies similar to those employed by large international corporations such as Coca Cola to market their products. This approach is rarely seen in the U.K..

AM: You have created work as the outcome of several residency projects; with the British Council in Shanghai, at Age Concern, at the Chinese Arts Centre and at the Lightbox Gallery & Museum (which holds archival material from Brookwood Hospital, a former mental asylum). You obviously respond positively to the format of the ‘artist’s residency’, could you tell me about your experiences as an artist-in-residence and how it has shaped your practice?

EF: Each of the residencies has provided a unique focus and support for the development of a new body of work. For both the Age Concern and Lightbox residencies, the topics for exploration were chosen by the commissioning organisation, and therefore had specific remits and goals for the artist to consider and fulfil. For the British Council and Chinese Arts Centre residencies, however, the subjects were chosen by me which therefore allowed a higher degree of freedom for exploration. Nevertheless, all of them have provided resource material for research, an opportunity to work with their staff and participants, and supportive environments for the production of new works. For instance, Age Concern gave me the opportunity to work with older people with dementia, while the Lightbox enabled me to access the archive of the Brookwood Asylum to produce a film that was inspired by and drew on it. Both the Chinese Arts Centre and British Council provided a studio and support for travelling and meeting people in Manchester and Shanghai respectively for the T.C.M. and Western medicine projects.

AM: One of the most striking sights on a visit to China, and the subject of your video Good Morning Shanghai, is groups of elderly people practicing Tai Chi in municipal parks. From your experiences in Shanghai and as an artist-in-resident at Age Concern in the U.K., how would you compare our attitude to the elderly in Britain with that in China?

EF: It was wonderful to see so many older people maintaining the tradition of doing morning exercises in public spaces in China. In addition to providing health benefits, these daily gatherings also offer an important opportunity for them to socialise with each other rather than staying at home in isolation. During my Age Concern residency, I visited older people with dementia both in their homes and at the day centre. Some of the daily activities at the day centre include having tea, playing music and dancing, which provide an opportunity for them to socialise with each other. Although I have worked with older people during both residencies, the two groups are very different in nature – the older people in Shanghai came from the general population, whereas those at Age Concern had dementia. It is therefore very difficult to compare our attitude to older people in Britain with that in China based on my experience during these two residencies.

AM: Your experiences working as a medical doctor inform your subject matter as an artist. Was there a Road-to-Damascus moment when you suddenly changed from wanting to practice medicine to wanting to practice fine art? Or was it a more gradual process? How do these two different approaches to the human condition, that of the doctor and the artist, compare?

EF: It was a gradual process. I have been interested in art since I was a teenager. I was good at traditional Chinese painting and calligraphy when I was growing up in Hong Kong. However, when I moved to Canada at the age of 18, I spent most of my time studying and then practicing medicine, and not making any art. By the mid-90s I had been practicing medicine for well over a decade and felt I needed a new challenge. This coincided with my mother being diagnosed with a terminal illness, which made me re-evaluate my own life goals, and made me realise the importance of art in my life. I then completed a B.F.A. at a Canadian University while practicing medicine part-time. I came to London to do an M.A. in Fine Art at Goldsmiths College in 2000, and since then I have been working as an artist and have not practiced any medicine.

The practice of medicine involves analysing a person’s health condition, making a diagnosis, and then prescribing a proven treatment. It is a problem-solving rather than a creative process. As an artist, I am more interested in the social aspect of medicine, and in understanding how biotechnology, illness, disability etc. impact upon humans as social beings. Rather than attempting to solve problems and looking for consensus, I aim through my work to create new ways of asking questions and encouraging debate about various issues concerning the human condition.

AM: To what would you attribute the continuing popularity of medical dramas on television? Would you say they play out our darkest fears about the vulnerability of the human body?

EF: I rarely watch medical dramas on television, perhaps partly because I already have first-hand experience of some of these scenarios, and also partly because I think a lot of them tend to be over-dramatised. I also get a bit irritated when I see the X-ray on the lightbox in the background is installed backwards, which happens quite often, and spoils my suspension of disbelief.

Anyway, I think the continuing popularity of medical dramas on television is likely to be due to an intrinsic curiosity about the human body and, as you said, its vulnerability, mutability, pleasure and pain.

AM: I see from your earlier works, such as your soft sculpture of a mouse with an ear on its back, that you keep abreast of developments in medical science. Does anything ever surprise you? Do you have any predictions about our medical treatment in the future? Are you interested in the ‘ethical’ issues surrounding stem cell research?

EF: Yes, I am still very interested in knowing about the latest developments in medical science. I am often surprised by and marvel at new developments in genetics, tissue and organ culture, nanotechnology etc., and the explosive speed at which they are developing. I think the way forward for medical treatment in the future lies in the areas of genetics and nanotechnology.

I am certainly interested in medical ethics. Unfortunately, the historical trend has been that the development of ethics tends to lag considerably behind the development of biotechnology. Ethics has always been trying to play catch up with the latest biomedical development, thus constantly being reactive rather than proactive.

Another issue that I find compelling is the politics of the allocation of resources. On one hand, it is great that allocating resources for biotechnological developments will improve and prolong life. On the other hand, with more people living longer, coupled with the problem of unsustainable exponential global population growth and the rapid, perilous depletion of natural resources, one needs to question how our limited resources should be allocated.

AM: What new projects are you working on at the moment?

EF: I am working on a photography and film project about facial disfigurement. The idea central to this project is that, although disfigurement affects a large number of people in the UK, its visual representation (or mis-representation) in the arts has not been extensive. In addition, there has been a historical tendency to associate people with disfigurement with negativity and monstrosity. Through this project, I hope to raise awareness of issues relating to facial disfigurement.

Ali MacGilp and Eric Fong

Eric Fong Ways of Seeing: Blindness and Art 2008

Eric Fong Shanghai Remedies: Portraits: Mr Hu, Retired Martial Arts Teacher 2006

Eric Fong Good Morning Shanghai film still 2006

Eric Fong Toy Story 1 2001