You take your inspiration from ancient texts, architectural features in your surroundings and the history of spaces. How does your creative process work?

I would like to start by acknowledging that construction and destruction equally co-exist in my relationship with the history of spaces. I am very fascinated by the voids that institutional history provides us. At this very moment, I begin to imagine new events that may have occurred on another timeline, an alternate history; perhaps spoken about, but never officially documented. Chronology is a conservative body in my practice; so I impede this orderliness with re-situating events in history either by interfering epochs with alternative fictitious happenings, or continue a bygone formation up to the present day, that originally started and ended in the past, synthesizing it artificially with the industrial and technological progress, that has evolved throughout history.

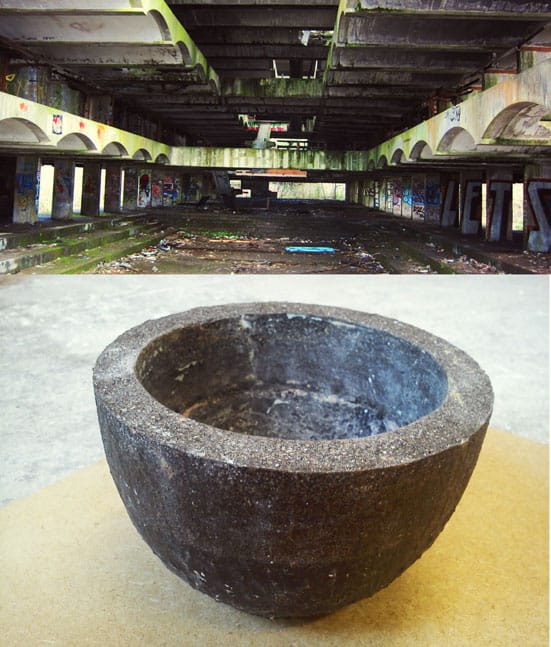

On the other hand, ancient manuscripts and architectural artefacts have truly possessive presence in the reality I construct for myself. I believe in their experience of time and being, which we can never have access to. For my recent project, I collected various haunting relics from the remains of Grade A listed St. Peter’s Seminary; one of the first modern ruins of Britain. Having been the literal carrier of bad memories, accomplishments and failures of this impressive venue, those objects were grounded down to powder and cast into a vessel, who is also a ‘carrier’. So the memories of different objects were literally transmitted into another object, to their second life. I am planning to make a few more vessels from different abandoned schools in Glasgow that share the same fate: Civic repurposing, destruction by fire, artistic and urban repurposing …

So if I have to narrow down my creative process into steps of actions, this would start with urban exploring, then hoarding; finally transforming and making go hand in hand. Eventually the work becomes independent, and goes out of my hands.

Your sculptures tend to contain kinetic elements. How did movement become integral to your works?

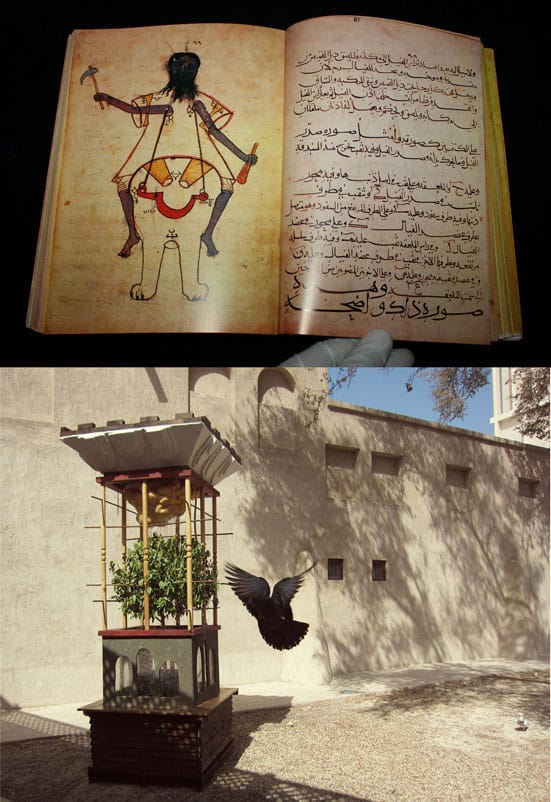

Before coming to Glasgow, kinesis was performed by the organic components of my installations. Transformation was in the form of degradation; failure was still a common outcome. Since I arrived in Glasgow in 2008, I literally fell in love with the beauty of monumental industrial machinery, the aesthetic and engineering behind the Victorian steam engines. My husband Tom Harrup has always been an inspirational mentor in teaching these mechanisms. I also really enjoy the idea of a ‘free machinery’, who doesn’t have to fulfil the desires of human being by working perfectly in order and providing what is demanded. My kinetic sculptures give these gears and cogs, their free will; and perform for themselves. I don’t think I enjoy being in the foreground. These mechanisms surely fail too, but I learned to embrace the rules of beautiful unexpectedness.

You recently took part in a residency in Dubai and this year you are returning there to make a film. Could you tell me a bit about your relationship with this unusual city?

Perhaps many people wouldn’t agree with me, but I find Dubai immensely fascinating. As we would all acknowledge; there is no medium limitation for contemporary art, especially today. I think Dubai itself is a very big-budget art project, organically continuing its life. It is bizarrely prophetic, if we have to imagine the creation of ‘everything’ from ‘nothing’. A more comprehensive text of mine was published in Satellite Voices about this issue during my first residency.

www.denizsdubairesidency.blogspot.co.uk

The city is so inspiring that plenty of ideas for different projects begin to come down on you, and time feels so limiting. An idea for a film possessed my thoughts during my first residency, but I did not ever imagine a possibility of actualising this dream. Rami Farook from the amazing art space Traffic in Dubai, became my Aladdin at the opening day of Art Dubai, and has always had his trust in me, with my unorthodox ideas since then. Now, a new film produced by Rami and directed by myself will be completed at the end of March.

The voids in history I previously mentioned are abundant in Dubai. Bedouin culture, thus orality prepared the perfect foundation for narrating alternative pasts for the city. I’m doing my best to make use of these little moments, productive gaps.

http://denizsdubaifilm.blogspot.co.uk/

You are going to Seoul later this year for a residency. Do you already have plans for what you will do there? Do you find the residency model suits your practice?

Yes, I do have a plan actually, a project of its first kind in my practice. I will fabricate an alternative community that resides in the interim space where the borders of the city walls of Istanbul and Seoul overlap. However, this interval will not introduce a new identity, rather a cultural product that had appeared at an unknown past in its history, having been presented to the inhabitants of Seoul in the present, or perhaps better to say in the future.

The research regarding this fictitious community will result as works based in various media, such as a docu-fiction film on customs and traditions, interviews carried out with locals; costumes, sculptures as cultural artefacts and drawings of maps and texts created as historical findings. This community will also have their own flag and dialect, which will be apparent within the work. Finally this installation will compose The Museum of Türgen Culture and Heritage. I heard that there is a Turkish speaking community in Seoul; I might try to contact them as the first thing.

I think, city walls are loaded with meanings; they are like an organism’s skin, and therefore must form a protective layer, yet be porous enough to allow a regulated passage or trade, from outer to inner, and vice versa. They would have defined one place from another. The walls of Istanbul have been surrounding the city since the 5th century. Parts of the walls still stand, however they no longer denote meanings of distinction. On the other hand, the walls of Seoul were built in the 14th century for the same reason of protecting the capital, which encircles what is now just the centre of Seoul. Both city walls once functioned as architectural borderlines, and now act as a gauging agent that has witnessed centuries of cartographical amendments.

Geographic borders remain as territories of conflict, between North and South, East and West; wherever we situate ourselves on the globe. The transgression of these creates a shifting meaning that remains in flux. My goal as a resident artist in Seoul is to blur any identified boundaries in order to raise questions, as opposed to answering them and thus pinning down what is already allocated to systems and classes.

Since I discovered that seeing new places (devoid of prejudices) and learning by traveling just like a flaneur, (almost active in a submissive manner), are far more exciting than being an artist. Residencies give me the chance to satisfy both, so they are ideal options for me.

You left Istanbul for Glasgow – tell me about your love affair with this post-industrial Scottish city and how it inspires your practice?

I feel like a traitor for not favouring my home city that I lived for 25 years; but Glasgow has a very special place in my heart; it is indeed a love affair! First of all, it is the place where I discovered embracing anything that composes my identity, and added these into my work. Those personal layers rendered my work special, rather than solely being an illustration of a theory once read.

I don’t often show my work in Glasgow, nor go to many openings despite Glasgow’s fame in the European art scene. I rather feed from the urban/natural landscape of the city; as well as its impressive history of foundries, railway tunnels, docks and the sudden fall after the WW2. Witnessing cut-off Victorian railings at the garden of your tenement has a special past of being used for weaponry in the World Wars. These little often overlooked details are ceaselessly waiting to be discovered on a simple Sunday walk.

When Glasgow was a very rich city, impressive school buildings were often built by several different architects, however this was not the case in the rest of the UK. Therefore you have plenty of experimental and grand architecture in Glasgow and fantastic stories behind to discover. I would never imagine in the past that, I would have adored a scene with a burned car by the river, with a wild life bursting from within.

https://vimeo.com/53796525 Trailer for ‘69’, HD Film, 29.30 minutes, 16:9.

https://vimeo.com/41619855 For video documentation of the mechanisms: ‘Somewhere in the Middle of Two, Southwest of One, and North of the Other’ (The Glasgow Tower) Three kinetic windcatchers dedicated to Glasgow, Istanbul and Dubai, disseminating respectively humidity, scent and sound. Each tower is 320X100X100cm, 2012.

Ali MacGilp

Work in Progress. Vessel made out of St. Peters Seminary, Cardross.

Work in Progress. ‘Beyond is Before’, a feature film commissioned by Farook Foundation, Dubai

Work in Progress. Maps of the old city walls of Istanbul and Seoul in preparation for a three-month residency at the Geumcheon Art Space, Seoul.

Above: From ‘The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices’ by Al Jazari, in 1206.

Below: ‘Somewhere in the Middle of Two, Southwest of One, and North of the Other’ (The Glasgow Tower) Three kinetic windcatchers dedicated to Glasgow, Istanbul and Dubai, disseminating respectively humidity, scent and sound. Each tower is 320X100X100cm, 2012.

69’, HD Film, 29.30 minutes, 16:9.