Last year Documenta 13 came to Kabul. There were workshops and a satellite exhibition in Kabul, as well as a presentation of Afghan artists in Kassel, some established some emerging. Other works at Documenta 13, by Mario Garcia Torres and Michael Rakowitz for example, responded to Afghanistan’s recent history.

How did you find the role of curator for the Kabul-based part of the project? What challenges did you face?

Honestly, I’ve never considered myself a Curator, and my approach towards working with young artists has always been, and continues to be, more collaborative rather than curatorial. So the title ‘co-Curator’ was there, but my role was really a continuation of what I have been doing for the last years in Kabul, Working closely with young Afghan artists and finding opportunities for them to participate in seminars, workshops, and exhibitions both in Afghanistan and abroad.

The challenges were trying to convey the idea of what dOCUMENTA (13) was to some members of the cultural administration, who had an understandably difficult time seeing our project as anything more than another donor-funded activity in the arts. Understandably because I feel that not enough time was spent discussing the project due to an overload of work and understaffed Kabul office.

Ultimately, my experience with d(13) as an exhibiting artist was, personally, far more fulfilling for me than the experience as a curator.

How was the experience for the young artists involved? Were some of the Afghan artists able to travel to Kassel?

The experience varied of course, with some artists expressing great joy over the seminars and workshops they participated in while others felt that their expectations were not met in terms of teaching quality on the part of the visiting artists and or tangibility of the seminar results.

Out of the 60 or so artists who participated in one or more of the seminars, 3 were selected based on their artistic practice and involvement with the seminars to exhibit with d(13) both in Kabul and Kassel.

Do you think the result will be a long-term positive impact on the Kabul art scene? How do you see it developing in the future?

It’s always hard to say what will have a long-term impact and what won’t, or what that was done will be sustainable locally and what won’t. But what many people outside of Afghanistan don’t realise is that there have been a multitude of seminars, workshops, and exhibitions organised and run by many people (including myself). Afghan artists have gone abroad to study or participate in residencies and workshops, the press/media has had a field day with stories about contemporary artistic practice in Kabul; money has been given for supplies and trainings, etc. etc. I call this phenomenon Afghanistan having become ‘Conflict Chic’ and have subsequently told all my artist friends in Kabul that with all the aid they’ve received it is now time for them to take responsibility for their own artistic practice and carry it forth. It’s now up to them.

How was your experience of participating in the Kochi-Muziris Biennale in December, India’s first biennial?

I had an amazing time working on the installation for the Biennale. I was lucky that they gave me the creative freedom to continue developing my conceptual approach to land. Territory, and identity through an entirely new installation work; essentially an archaeological excavation as installation exploring migration and politics while challenging dominant historical metanarratives. I also think my experience with working in Kabul all these years made it easier for me to navigate myself through my production hurdles without having to wait for the wonderful, but extremely overstretched, Biennale office production team to solve and/or provide things for me.

Could you tell me about the work you produced there, the mixed media installation What Histories Lay Beneath Our Feet?

History is inherently complex, as it must deal with retrospection and interpretation in an attempt to arrive at an understanding of the narratives woven by it. What Histories Lay Beneath Our Feet? is an attempt to not only explore these historical narratives, but to disrupt them, reinterpret them, and provide a way to represent history as both real and imagined, creating an entirely new narrative that challenges the dominating metanarratives shaping our experience with, and understanding of, the past and the present.

Rooted in my own familial story of migration from Afghanistan to India and back again, the installation uses archaeological excavation (itself a highly politicised discipline), documentation, oral history, and imagination as forms of resistance against attempts in Afghanistan and elsewhere to impose certain historical interpretations upon us, and to explore history and politics (both colonial and contemporary) as a way to reimagine the possibilities of the past, the condition of the present, and therefore the potentialities of the future.

How will you be spending your time in Dubai for your upcoming residency?

I’m currently still researching the Dubai project, but essentially I’ll be using traditional and modern architectural forms to explore, through a site-specific installation, the complicated negotiation Dubai is going through as it tries to create its traditional and contemporary identities simultaneously.

How do periods of time spent living in different cities influence your practice?

I’ve been lucky to have had the opportunity to work, since d(13) on context and/or site-specific works, giving me the opportunity to research a place and create a work that becomes a true dialogue with the place, rather than simply bringing in a pre-made piece to paste across the landscape.

What are you next projects?

I’m working on a proposal for the Istanbul Biennale this year and will be researching a new gallery/ies to work with. Importantly, my wife and I will be going to France to look for a warehouse space to convert as we’re actually looking to set up a base there where I can have a stable atelier again. This doesn’t mean I’ll stop doing site-specifics, but there are of course other works that require a defined working space. I’ll also probably see where I can lend a hand to friends in Kabul.

Two of my favourite of your works are the darkly humorous Payback and Jihad Gangster Afghan Parliamentary Campaign.

In Payback you comment upon corruption and abuse of power by dressing as an Afghan police officer and paying reverse bribes to Afghan motorists at a fake checkpoint, to apologise for bribes they may have been asked to pay by the Afghan police.

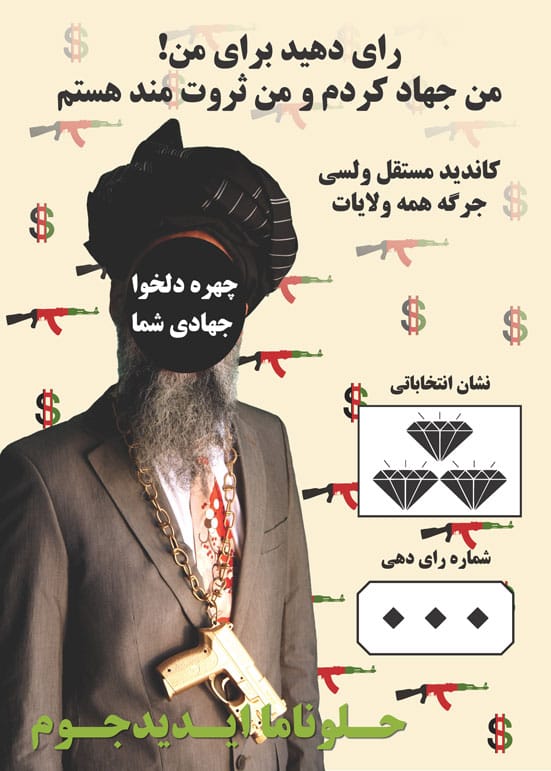

Jihad Gangster Afghan Parliamentary Campaign was your faux campaign for the Afghan parliament, in which your candidacy was advertised through posters across the city. The character you inhabit of the Gangster Jihadi combines aspirational ‘hardman’ stereotypes from your dual heritage. The rocket-launcher carrying, undefeatable Afghan ‘jihadi’, who fights foreign infidel invaders, and the bling-wearing American ‘gangster/ gangsta’, successful and wealthy criminals/ rappers.

How difficult were these two works to produce? How did the public react to these interventions? Were there any repercussions for you?

You would probably be surprised at how easy they actually were to produce. The only production problem I came across was with the parliamentary poster campaign where it was difficult to find a printer willing to print them; actually it was impossible, as they feared retribution. I finally found a back-room poster printer in a dubious construction office that belonged to a friend of a friend of someone I knew in Kabul.

The public reacted great, which is understandable since these works were born directly out of conversations I had with locals about police corruption and warlord candidates. Of course, not everyone was pleased, and the posters didn’t last one week on the walls before being ripped off or covered up.

There weren’t any repercussions, although someone did complain to the elections commission about the posters. The commission was preparing to launch an investigation to see who was behind it when voting took place and so dealing with real cases of fraud and electoral corruption occupied all their time.

Your experience of living between two cultures, growing up Afghan in the American South, lies at the core of your practice. You explore a ‘geography of self’ combining personal experience and anthropological research. How differently is your work received in Afghanistan, in the United States and in other countries?

I think it all depends on the work. I think the dark humor is better received in Afghanistan and Europe, while America in general has a hard time laughing at terrorism. But then again, Conflict Chic (both the fox-lined military vest and the designer suicide vests) was not received that well in France by some who felt I was making too light of a grave and tragic situation.

And actually, if this says anything about it, I’ve yet to be approached by American galleries to work with them, and none I have approached have replied positively. In the meantime, I’ve shown and sold more in Europe (mainly Paris), the Middle East (mainly Dubai), and the Far East (such as Hong Kong). But the KHOJ Residency and the Kochi/Muziris Biennale have also introduced me to more of what’s happening in India so I’d like to explore that further.

Ali MacGilp

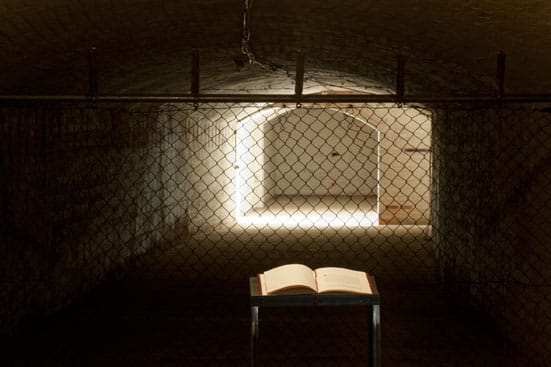

Amanullah Mojadidi, Resolution, commissioned by documenta(13) (2012, Photo Credit Nils Klinger)

Amanullah Mojadidi, What Histories Lay Beneath Our Feet, commissioned by 1st Kochi/Muziris Biennale (2012, Photo Credit Benjamin Pritchard)

Amanullah Mojadidi, Payback Performance, Screen Still (2009, Courtesy of the Artist)

Amanullah Mojadidi, Payback Performance, Screen Still (2009, Courtesy of the Artist)

Amanullah Mojadidi, Jihadi Gangster for Parliament Campaign Poster (2010, Courtesy of the Artist)

Amanullah Mojadidi, Jihadi Gangster for Parliament, Campaign Poster Installation 1 (2010, Photo Credit Karim Amin)