22nd May 2007 — 2nd September 2007

Selecting

500 images to tell 'the story of British photography', from its

inception in the 1840s through to its ubiquity in the present, must

have been an almost overwhelmingly mind-boggling task for the curators

of How We Are: Photographing Britain. Given the infinite possibilities

of such an ambitious brief concerning such a vast timespan, deciding

what to include and what to omit - not just in terms of particular

photographers, but also in terms of the events, people and places

depicted - must have proved stupendously difficult. Curators Susan

Bright and Val Williams hardly need inform us in the exhibition

catalogue that the resulting show doesn't purport to be a definitive

survey, and that the images were selected with prejudice; after all,

how could it be otherwise?

Despite this disclaimer, it feels like they have largely

succeeded in conceiving an exhibition that presents a fairly diverse,

inclusive and often intriguing picture of both Britain and the

photographing of Britain over the last 160 years. Consequently the

display seems free from any kind of agenda or pervasive theme,

steadfastly refusing the temptation to construct or uncover an

overarching mythology, or mythologies, of Britain or of (that fatuous

notion) Britishness. On the one hand, this is an admirable achievement,

but on the other hand, the overall effect can feel at times quite dry,

and often rather flat and unmoving (though in one sense of course,

photography cannot be anything else). Perhaps flatness is the price you

pay for a stab at objectivity, but in the absence of the possibility of

constructing a definitive narrative, maybe the curators could have

really embraced some of their prejudices, and delivered a show that was

heartfelt and provocative. This criticism is a bit unfair though - we

can't (usually) have it both ways.

Actually there is a certain appeal to the flatness of the exhibition,

and it is linked to the influence of conceptual art (as pointed out by

David Campany in his essay on the show in the Tate etc magazine) on the

show's curation and on some of its more recent photographers. Indeed,

if there is a common thread to be discerned in the show, it is that the

images on display don't tend to encourage, or even allow, any kind of

extra-interpretive, meta-textual reading. This isn't to say that one

would not in every case be possible, but to highlight that the images

here consistently seek to deny our interrogation. They refuse to yield

up their secrets. In attempting to show 'how we are', many images

stubbornly proclaim nothing more than, 'here I am' or 'here it is' or

'this is it'. Many of the works on display, and the subjects therein,

are invested not with the hoary old cliché that 'the camera never

lies', but with an attempt to both acknowledge and get beyond the

truism that 'the camera always lies'.

There is obviously a huge amount of exceptional photography

here worthy of mention, but to pick a few personal highlights ... One

of the most compelling selections here is the remarkably rich work of

John Hinde, a pioneer of colour photography whose images had no

pretensions to being anything other than illustrative. Paradoxically

both very ordinary and exceedingly strange, though not unnervingly so,

the images taken from his book 'Citizens of War - And After' appear as

though they were designed to convey instant nostalgia, and now look

like stills from a Dennis Potter play. Furthermore, it was something of

a postmodern masterstroke to include some of Hinde's glutinous,

pastel-hued images of assorted plates of food as found in the surely

fascinating instructive manual published in 1947: 'The Small Canteen:

How to Plan and Operate a Modern Meals Service'.

Another set of photos that reveal the gentler, more innocent Britain of

the past (however much of a hackneyed, fictitious notion that may be)

are those of Alvin Langdon Coburn, particularly a now rather poignant

image taken in Leicester Square on a rain-soaked evening in 1909. Taken

from the gloom of the park in the centre, through the trees, towards

the shimmering, luminous façade of the Empire Theatre (the Empire

Cinema since 1927), viewed today, this entirely unpopulated shot evokes

the Leicester Square of a century ago as what it perhaps once was: a

place of real wonder and possibility, of excitement and anticipation.

To witness what it is now - an ugly hymn to the McDonaldisation of

culture - is to witness how the myth that Coburn's image presents has

been grimly exploited.

An interesting supplement to this, at the other end of the exhibition,

in the section entitled 'Reflections on a Strange Country', is Stephen

Bull's series Meeting Hazel Stokes, a collection of shots featuring

theatre usher Stokes posing benignly alongside various minor

celebrities, backstage at a Canterbury theatre. Like a great deal of

the photography here, the images were of course never intended to be

'art', taken as they were mostly by Stokes' husband, before being - in

that slightly cynical, slightly sinister way - appropriated by an

artist. The result is a weird, almost scary piece, that reflects in a

resigned, sardonic fashion, on that peculiarly modern neurosis:

requiring not only that our identity be somehow validated by

celebrities, but looking to them to plug the emotional and spiritual

absences in our lives. Looking to them to complete us. This is

undeniably an aspect of what Britain has become. A strange country

indeed.

DF

Tate Britain

Millbank

London SE1 9TG

http://www.tate.org.uk/britain/

Open

Daily, 10am-5.50pm

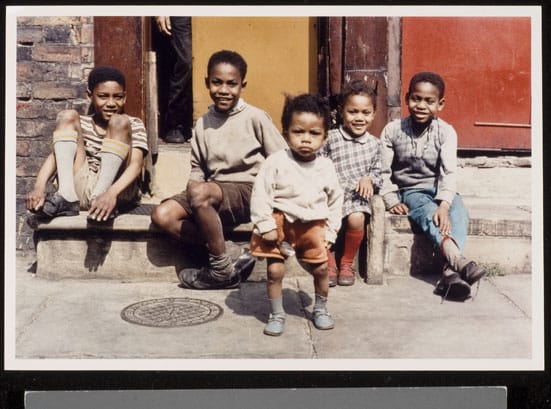

Shirley Baker

Hulme, Manchester 1965

(c) The artist

C type print