19th September 2007 — 28th October 2007

The

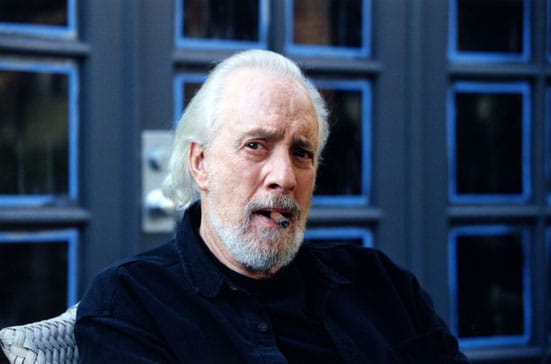

un-credited screen writer is a ghostly figure erased in the illusion of

cinema. In Robert Towne, 2006, Sarah Morris reverses the

camera onto the writer and presents what is described as a 'portrait'

of a script-doctor whose work includes many classic blockbusters from

the 1970s onwards. Shown for the first time in the UK at Whitechapel

Gallery, Robert Towne follows Morris' Los Angeles, 2004, which reduced

the reality of that city to the fantasy world of Hollywood and the

film industry. Here Morris continues to explore the mechanism behind

the cinematic representation of reality, in order to pursue the

perception of reality as such.

The film resembles a documentary-style interview where an absent

questioner barely needs to encourage a loquacious Towne to discuss his

role in the creation of hit films such as Chinatown, Bonnie and Clyde

and Shampoo. Towne is especially insightful when explaining the

commercial success of thrillers like The Parallax View by describing a

culture obsessed with conspiracy in the post Kennedy assassination

era. He suggests that these films fed the desire of an audience awake

to political conspiracy and hypocrisy and concludes that they 'did

their job too well, there was nothing left to expose'. Towne

ultimately proposes that all films are really just about conspiracy.

The film opens with Towne taking a big puff of his cigar and beginning

'Well, ah…,' proposing that what follows is a documentary portrait and

leading us to expect the usual illusory techniques that make reality

palatable, (illustrative material of the films that Towne discusses,

for example). Instead, the 34 minute film consists of a monologue.

Towne is shot in three locations in his house, the image of his

talking head interrupted only by the very occasional view of his desk

or hallway. However, Morris introduces subtle allusions to cinematic

technique that stand out in relief against the unchanging visual

content. Atmospheric music suggests a building in tension, although

the tension here concerns no more than Towne becoming excited about a

point and the music fades out once he has made it; hardly a

blockbusting climax. Likewise, uncomfortable and seemingly unnecessary

cuts throw us awkwardly between Towne's sentences. Morris' film enjoys

the paradox of a central character who is an expert in the illusions

of film and for whom a film-maker is 'an anarchist who wants to

control a fantasy world'. Her exaggerated editorial techniques

deliberately draw attention to the methods by which film- makers

construct a picture of reality. By adopting these authorial tactics to

build her own portrait of Robert Towne, Morris suggests a slippage

between her film's form and its content.

Morris' film is only minimally a documentary and requires the language

of art film for interpretation. However, presented in the screening

room as part of the Whitechapel Laboratory series, it forces us to

become cinema viewers and denies us the transitory approach favoured

by the gallery visitor. Yet Robert Towne is sparser than Morris'

previous films in the sort of visual content that would help to

communicate its complex experiments with form to a broad audience. It

often feels like an exercise in discourse rather than either of the

visual forms it resembles. While Robert Towne the man is a charismatic

subject, the presentation of Robert Towne the film threatens to

obscure the insight we find in his words.

SH

Whitechapel

80-82 Whitechapel High Street

London E1 7QX

http://www.whitechapel.org

Open

Wednesday-Sunday, 11am-6pm