7th December 2007 — 10th February 2008

I walked into this temptingly titled exhibition rather grumpily, having

circled the surrounding streets for ages in search of a parking space.

In this frame of mind I initially saw little to set it apart from a

number of provincial collections I've half-heartedly wandered around on

rainy afternoons: eclectic groups of artefacts, together by

happenstance, like a jumbled accumulations of ornaments on an

octogenarian's mantelpiece. Some of the familiar work shone out

immediately. A Jenny Holzer sign brightened me for a moment, but I was

trying to discern Steven Claydon's hand in the affair and, besides his

bronze one with a section of armature revealed partway down a finger,

was drawing a blank.

He must like hands. There's one on a plinth, also disembodied,

once belonging to a mannequin, faded and cracked with age. I expected

it to be from the days of the surrealists, but was surprised to learn

that it was dated 1976. And heads. A vitrine contains a Giacometti, an

Epstein. Nearby, upon a hessian-lined table that extends diagonally

across the main room, a goggled Frink. There are Claydon bonces. One,

white, bearded, resembling a Viking Hemingway with white earflaps,

crowned with a dark pudding-bowl headpiece. 'Spaka Spou (deposed

deity)' says the catalogue. Sigmund Freud, whose house I'd driven past

three times earlier, sprung to mind. I was thinking of his study,

heaving with archaeological curios.

His collection includes deities and mythical creatures from

antiquity that he used as metaphors for psychoanalysis. He tended to

gesture towards particular ones to illustrate remarks he made to his

patients. Freud was evidently a compulsive collector. Like the work in

this exhibition, his pieces had not been selected or arranged according

to chronology or place of origin. Instead they served as points of

departure. Freud's objets

emanated from scattered cultures, and time-wise, span millennia.

Claydon's selections, at least in terms of their actual creation, are

confined to the 20th and 21st century western art canon. Mournful

drones and discordant caterwauling issue from a corner of the room. A

video by Jim Shaw depicts bespangled figures with giant Mr Potatohead

ears, noses and miscellaneous body parts performing some kind of

delirious Shriner ceremony within a curved wooden wall of death.

Outside the viewing area is displayed one of the props: Latex rubber

testicle bagpipes. A blanched gargoyle by Thomas Houseago crouches in

the corner below Picabia's 'Femme a l'Idole' featuring a stocking-clad

woman standing with her knee in the crotch of a fantastical ebony

sculpture. The warm tobacco glow of this image is one of the few

smudges of colour Claydon has allowed in this room, the hues

complementing those of Burra's 'Design for a Drop Curtain' on the far

wall showing grotesque masked entertainers and hooded cloaked women

throwing shapes in a brutist city square receding to an exaggerated

vanishing point. Throughout the exhibition he has 'used' colour

sparingly. He has considered the effect of the pieces in each room like

an interior decorator, prioritising tone over colour, and, in the case

of a wall of unphotographable off-white paintings by Keith Coventry,

dispensed with tone altogether. A smallish dun-coloured Lynn Chadwick

sculpture leans against the wall below them. One exception, a lurid

pink haemorrhoid cushion of aluminium by Franz West in the adjoining

room sits below a video by Mark Leckey entitled 'The March of the Big

White Barbarians.' To a rousing chant, a slideshow of corporate

sculptures, the kind that are so ubiquitous in cities, standing stock

still as only sculptures can, where they have been sited, regardless of

being in or out of fashion, great big lumps of bronze and stone that

ultimately become invisible to all but the tourists. The video includes

a Chadwick. Could it be the one that actually did disappear recently,

half-inched and believed to have been melted for scrap? A lot of the

elements in this show repeat and resonate in other parts of the

gallery. Maquettes of the Paolozzis in the video can be seen again on

the hessian table. A miniature Incredible Hulk in plaster has all the

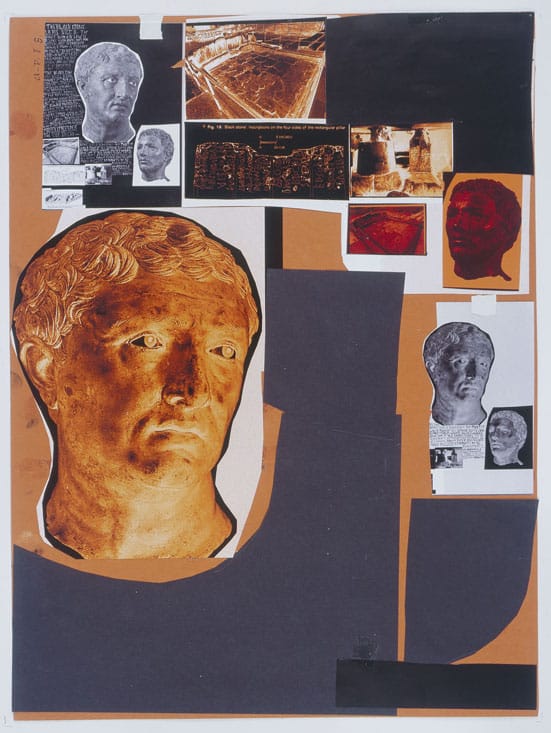

musculature of the collages of Roman statues in the next room,

accompanied by scratchy handwritten comments and transcriptions of

inscriptions carved on the plinths: 'Whoever defies or contaminates or

even merely traverses this plinth let him be forfeit to the shadows of

the underworld.' Again I'm fooled by the style of the pictures. They

have the austerity of the war years about them. Nope. Richard Hawkins,

2006-2007. Hidden away in an arched side room is Simon Martin's

'Carlton'. The video lovingly tracks the contours of Ettore Sottsass's

totemic bookshelf whilst a soothing night-time radio voice intones

pithily, ruminating on many issues that Claydon seems to be hinting at

in this fastidiously planned arrangement. He has written a manifesto of

sorts in the catalogue, which jubilantly veers between hardboiled art

theory and full-on neo-dada scatological rant, cunningly ending in a

resounding implosion as he claims the title of the show, allegedly

taken from a Charlie Chan story, never actually existed. Strange

events? Later, I found myself in the toilet downstairs, appraising the

white porcelain, trying to understand the pipework, and then, the

display of shoe soles in the dry cleaner's and the pictures of English

hunting scenes on the wall of the Hellenic restaurant in the Finchley

road. Perplexing.

PH

Camden Arts Centre

Arkwright Road

London NW3 6DG

http://www.camdenartscentre.org/

Open

Tuesday-Sunday, 10am-6pm

Wednesday, 10am-9pm

Richard Hawkins

Urbis Paganus I

5" 2006

Private Collection

Courtesy Galerie Daniel Buchholz