Wafaa Bilal’s The Hierarchy of Being is an invitation to consider the ways in which pioneering Islamic scientists have shaped contemporary thought. The project was fuelled by the artist’s interest in the work of Ibn Al-Haytham and Al-Jazari and their outstanding contribution to scientific knowledge in the fields of optics and kinetics. Both were active during the Golden Age of Islam, which lasted from the eighth century until the Mongols sacked Baghdad in 1258.

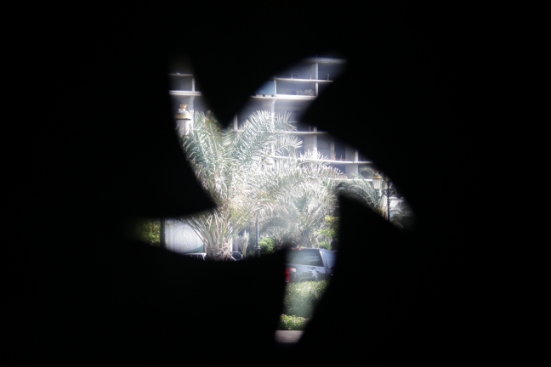

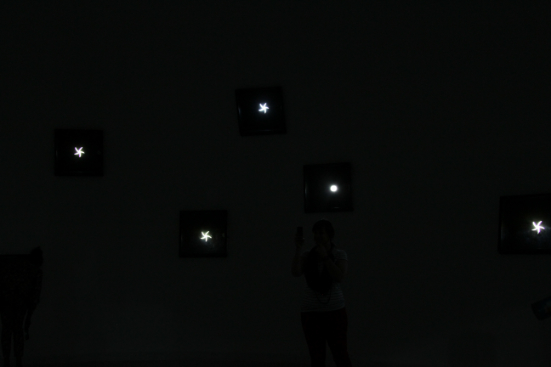

Bilal’s sculpture is a large camera obscura located in the Maraya Art Park in Al Majaz Waterfront, Sharjah. It has fifteen windows with motorised irises, programmed to open for ten minutes, then close for fifteen. They allow the eyes to adjust to the darkness, after which inverted images from the park are projected inside the space. When the windows open again, the image fades away. To create a camera obscura, ‘darkened chamber’ in Latin, you need to make a hole in the outside wall of a room so that light filters through into the space, if dark you will then see an upside down image of the scene outside.

The Hierarchy of Being is curated by Sara Raza, who enlisted two architects from the Royal College of Art to design its elegant exterior. It remains in Sharjah for this year’s Capital of Islamic Culture then tours internationally.

The interior of Bilal’s sculpture is cool and calm, a space of contemplation, from which visitors are invited to wonder at the enchanting and startling effect of light forming images of the outside world in the dark. The idea of a world turned upside down has allegorical potential. In Bilal’s work, the image is left inverted, there is no mirror or lens to ‘correct’ it, as in the eye or the camera. The image of the world outside remains mysterious and unresolved, a second-sight procession. It is ephemeral, not recorded. We are offered momentary liberation from the tyranny of surveillance we are subjected to via social media. Experiencing the work sparks reflection on the subjective character of memory itself and the human desire to understand the nature of vision, perception and representation, both physically and intellectually. In Western art history, there has been impassioned debate around how much renowned artists, such as Vermeer relied on the camera obscura in producing their oeuvre.

The principles of this device were first recorded by the Chinese philosopher Mi-To in the fifth century BCE and explored by Euclid and Aristotle. Ibn Al-Haytham, however, in the tenth century, was the first to successfully project an entire scene from outside onto a screen inside and is acknowledged as the inventor of the camera obscura and the pinhole camera. This Iraqi polymath is also recognised for his significant contributions to the fields of optics, astronomy and the scientific method.

Time is a very important element in Bilal’s sculpture. In our Internet-dominated culture of instant gratification, Bilal invites us to experience the camera obscura with our own body in real time within the cycle of the windows’ movements. It is an arresting thought that this ancient technology would eventually spawn photography, cinema and the mass media.

Bilal first garnered international attention with works using cutting edge technology and that were explicitly influenced by his personal narrative. Forced to flee Iraq, Bilal lived in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait before moving to the USA permanently in 1992. Bilal’s brother was killed tragically in Iraq in 2004 as the result of a drone missile attack on a checkpoint.

Bilal examines the points where our interaction with other people via the Internet impacts on the human body in all its corporality. In Domestic Tension (2007), Bilal set up an environment in which participants over the net could shoot at him with a paint ball machine. This work can be interpreted as Bilal’s attempt to assuage his survivor’s guilt over his brother’s death. It is also a critical comment on the detached technologies of death used in contemporary warfare, such as drones, which, despite their supposedly surgical-like precision have killed large numbers of civilians. I also read Domestic Tension as a timely update to Chris Burden’s seminal performance work Shoot (1971) carried out against the backdrop of the Vietnam War.

In his project and Counting… (2010) Bilal had his back tattooed with dots representing the casualties of the Iraq War. The 5,000 American casualties were inked in red and the 100,000 Iraqis marked in green UV ink, that can only be read under black light. The work is a commentary on the way casualties are reported in the US media and on society’s selective vision. Bilal returns to this theme in his latest project Myi, an app he is developing with Kamel Lazaar Projects. It will enable users to upload images, uncensored and unedited, from their smartphones to a platform that aims to produce a picture of contemporary events more accurate than that of the mainstream media.

For 3rdi (2010-11) Bilal attached a camera to the back of his head, recording his daily activities and relaying them to the internet at one minute intervals. This relentless performance recalls the commitment of Tehching Hsieh in his One Year Performance (Time Clock Piece) (1980-81). Bilal also anticipates Edward Snowden’s revelations of indiscriminate government surveillance. For the artist, inserting an artificial eye into the back of his head was an attempt to capture the immediate past in an objective way, without editing or framing a shot, in a kind of anti-photography. Bilal’s attempt to become a cyborg was undermined by the fragility of his flesh, which rebelled with repeated infections, eventually ending the project. 3rdi coincided with the launch of Instagram, which has given us the ability to record every detail of our lives and offer them up to our peers for approval. Bilal’s work is antithetical to the contemporary culture of the ‘selfie’ as his body is absent from the frame.

In The Hierarchy of Being Bilal celebrates his culture’s contribution to humanity, a respite from media portrayals of Iraqis as victims or terrorists. Drawing attention to the Golden Age is particularly poignant given the awful loss of cultural heritage in Iraq and Syria during recent conflicts. During the Golden Age, a time of religious tolerance and freedom of expression, Baghdad was the intellectual centre of science, philosophy, medicine and education. It was home to The House of Wisdom, the largest repository of books in the world and centre of the movement to translate scholarly texts into Arabic. Bilal cites the inspiration on his work of the inventor Al-Jazari, who created automata and ingenious mechanical devices. One of his most spectacular creations was a boat of robot musicians. What strikes me about the Golden Age is that this was a time when technology appeared to be playful and innocent, rather than an instrument of terrible destruction.

Ali MacGilp

Wafaa Bilal The Hierarchy of Being 2013

Photo courtesy of Orlando V. Thompson II

Wafaa Bilal The Hierarchy of Being 2013

Photo courtesy of Orlando V. Thompson II

Wafaa Bilal The Hierarchy of Being 2013

Photo courtesy of Orlando V. Thompson II

Wafaa Bilal The Hierarchy of Being 2013

Photo courtesy of Orlando V. Thompson II

Wafaa Bilal The Hierarchy of Being 2013

Photo courtesy of Orlando V. Thompson II