4th March 2014 — 18th May 2014

Can art capture or express how it feels to be in ruins? The twin sense of that phrase is apt, for surely one of the most compelling instincts provoked by an encounter with ruins is a desire to get in amongst them, to be inside them, to penetrate. And in penetrating, to lose oneself. Whence, perhaps, the notion of Ruin Lust, the title of Tate Britain's exhibition on the subject - lust being a trope that has been associated with dereliction for as long as such things have been aestheticised. The notion that is it lust and not love that is, as it were, a bedfellow of ruination, suggests that ruins can never satisfy the promise of self-transcendence that they seduce us with; that, try as we might to inhabit and in turn be inhabited by ruins, we always find ourselves left on the outside of them. After all, ruins are places that, almost by definition, have turned the inside out.

This is all inextricable from the other, more personal sense of being in ruins, and the exhibition catalogue quotes the much revered W. G. Sebald to make what itself now seems like a well-worn observation, that 'the decrepit state of once magnificent buildings' can be felt to reflect one's state of mind. Such reflection is 'always on the lookout for the originary ruin', as Jacques Derrida writes in Memoirs of the Blind: The Self-Portrait and Other Ruins. It is a 'narcissistic melancholy, a memory - in mourning - of love itself. How to love anything other than the possibility of ruin?' This is a tension that gives dereliction its charge: a longing, a nostalgia, for a totality that never existed, and never could have.

The trope of ruin as portrait is perhaps most compellingly explored here in a revelatory sculpture by Eduardo Paolozzi, not an artist one usually associates with this sort of territory, despite the kinship that J. G. Ballard - one of the high priests of ruin aesthetics - felt for the man and his work. Paolozzi's Michelangelo's 'David' comprises a plaster copy of the head of the celebrated Renaissance statue sawn into several pieces and then reconstructed with wooden chocks wedged between the pieces, the whole thing bound together with twine. We are presented with a vision of the ruins of figuration, of the classical idea of beauty as something that modernity is barely managing to hold together, except through a kind of desperate shoring up of its fragments into a recognisable but irreversibly damaged likeness. It speaks too of the modern era's dissolution of the very idea of the self, and of the necessary charade of a unified subjectivity that has been left in its wake.

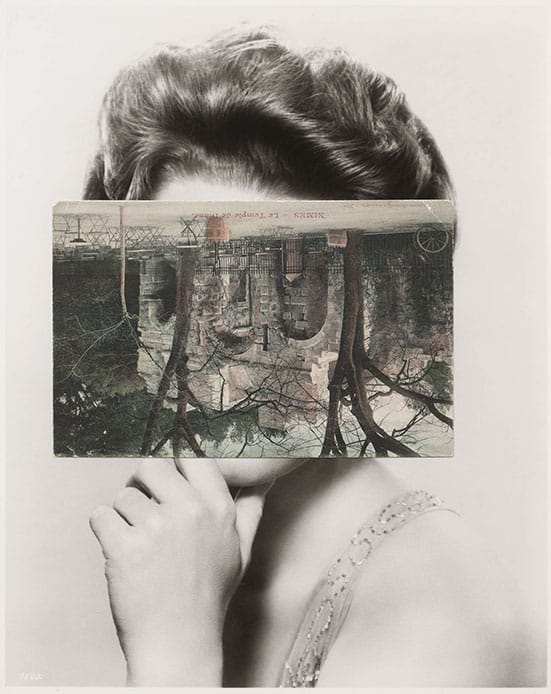

In dialogue with the Paolozzi are two of John Stezaker's trademark photo-collages from his Masks series, in which scenic postcards are placed over anonymous mid-century publicity shots of film actors, positioned so that the shapes in the postcards are closely aligned with the contours of the actor's face. Stezaker's work is almost always fascinating to look at, and one of the works here, Mask XIV, is superb. The postcard depicts two openings in a cliff-face, which take on the appearance of hollowed-out eye sockets, the vegetation beyond becoming like the complex, unknowable circuitry of the brain, or indeed the psyche. Intriguingly, the postcard is of a section of a Folkestone path, the 'cliffs' of which are actually man-made, though you probably wouldn't know it (and it's not clear whether Stezaker is aware of it). The knowledge of this extra layer of disguised artifice adds a further dimension of meaning to an image that is already concerned with the notion of the false face, the persona, and the impossibility of unveiling. It all makes for an absorbing study of the enigmatic and haunting relation between faciality, landscape, and place.

Reflecting on the Masks series, Stezaker has written of the influence of Maurice Blanchot's notion of being 'in exile from life in the world of images', which is a revealing way to think about the resonance of these playful and yet troubled collages. The violence Stezaker perpetrates on his found images is executed with such a deft touch, the reappropriation of once-everyday postcards coming to inscribe something akin to a 'death's space' - another of Blanchot's concepts that Stezaker invokes - in the image of a once-living person. But in doing so, Stezaker reveals something about the way that such space was always already there, not only in the always already ruined image of the self, but omnipresent in the entropic world around us and inside us.

This is a theme that suffuses the show's high point of Romantic ruination: Constable's Sketch for 'Hadleigh Castle' - a fine painting that's strikingly ahead of its time. Its ravaged tower presides over a landscape that hovers on the edge of abstraction, on the edge of collapse, as though the artist is channeling the entropy that is at work throughout the whole of nature. The technique, and the effect of the technique, anticipates some of Jack B. Yeats's best work, whilst the subject depicted recalls his more famous brother pacing the battlements in his late poem 'The Tower': 'And send imagination forth / Under the day's declining beam, and call / Images and memories / From ruin or from ancient trees, / For I would ask a question of them all.' Not unlike Yeats's poetry, Constable's painting is dynamic in a way that only timeless works of art can be. And it's pleasing to think that this Essex scene doesn't look so different today, two centuries on.

It's a pity that much of the other work here from the late 18th and 19th century rather pales in comparison. One room of the show largely amounts to just so many dreary watercolours of ruined abbeys and suchlike (but mostly abbeys), few of which linger in the mind. Almost all of these images feel so redundant somehow, almost completely lacking in any sense of drama or even melancholy. Where's the lust? Where, indeed, is the life? The most exemplary desolation is often that which, conversely, is the most alive.

There are a total of eight Turners here, most of which don't even begin to stir the soul in the way that they were surely intended to. Broadly speaking, this work hasn't aged well, but his Llanthony Abbey is memorable, in which the ruin is very much secondary to a nicely bleak, windswept take on the pastoral sublime, situated within which is the small solitary figure of a boy, who appears to be hollering into the sky, hat and stick held aloft, as the rainclouds move in. And one other Turner appeals immensely: a simple, uncharacteristic little image of Holy Island Cathedral - a distant, shimmering mirage of a ruin that emerges out of a sea of blue paper.

If the sludge of ruined abbeys and temples serves a useful purpose here, it's to prepare the ground for a much more interesting meditation on architectural space in John Piper's The Forum, which summons up a vivid sense of the fragmentariness of visual perception, or rather the way that any wholeness is always an amalgam of fragments. A large, fairly abstract vision of Rome in the spring, there's a warmth and looseness to it that is rare in Piper's work. Indeed it makes his other two canvasses here, both painted more than twenty years earlier, look very minor by comparison.

The deeper one ventures into this exhibition, the more of a misnomer its title seems. The co-curator, Brian Dillon, has clearly been thinking about this stuff for years, and one imagines that he now sees, quite rightly perhaps, ruins in everything, and everything in ruins. Perhaps this is why a lot of the work here, including most of the photography, is concerned more with the subject of place than with ruins per se. This is the case with images included from series by Keith Arnatt, Paul Graham, Jon Savage, and others. Savage's series Uninhabited London is a welcome addition to the show: evocative images of run-down corners of the city in the late-1970s - of a piece with Chris Petit's 1979 masterpiece, Radio On - summoning up a lost age whilst showing how little has really changed. Paul Graham is an interesting if rather overrated photographer, but the three images included here from his Troubled Land series - taken in Northern Ireland in the mid-1980s - lose almost all of their semantic charge in the context of this show. Keith Arnatt is also badly represented here. His 1980s series AONB (Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty) shows the infraction of the dross of the modern age on the 'natural' landscapes of Britain, but the images selected here are those of a a photographer who has already made up his mind about his subjects before raising his camera. In making images of the imposition of banality, he largely fails to transcend that banality. But the fault lies more with the choice of images than with the artist, whose best work is both witty and poetic.

The investigation and evocation of place is also one of the most prominent concerns in a number of works here by both Paul Nash and Tacita Dean. Nash has both paintings and photographs in the show, all of which will be familiar to anyone with even a passing interest in his work, but which are rich enough to sustain repeated viewing nevertheless. His 1940 photograph of wrecked WWII aircraft at a dump outside Oxford is a particularly welcome inclusion, and in its stark matter-of-factness is perhaps even more affecting than the celebrated painting, Totes Meer, that it provided the source material for.

Dean is represented not, as I would have hoped, by her film of the derelict 'sound mirrors' on Romney Marsh, but chiefly by one of her driest and most conceptual films, Kodak, which records on celluloid the manufacture at a French factory of this very material. It's an educational experience apart from anything else, fascinating and surprisingly beautiful to see the creation of this strange quasi-magical stuff we call film, and there is a real sense of wonder in this usually unseen process. For added poignancy, the closure of the factory turns out to be imminent, so there is a sense of the material mourning its own demise, bearing witness to its own obsolescence.

A final highlight of the show is 1984 and Beyond, Gerard Byrne's video and photo installation about the ruins of the future, or at least the ruins of a particular conception of futurity, which is based around the filmed restaging of a 1963 roundtable between sci-fi authors. I first wrote about this work on these pages when his gallery showed it in 2007, and it's still an highly engaging and unsettling piece, the exuberantly utopian proclamations of the speakers offset by the stillness and quietude of the downbeat photographs that line the room. Byrne's work addresses all manner of ideas, but insofar as this is a work about ruination, there is no lust here.

A mistitled show then, and an unfocused one. But nevertheless there's plenty of interesting art from Tate's vaults to be seen. And if it fails to cohere very effectively into a satisfying whole, given its themes of fragmentation and disarray, perhaps that is even quite appropriate.

David Foster

Tate Britain

Millbank

London SE1 9TG

http://www.tate.org.uk/britain/

Open

Daily, 10am-5.50pm

Jane and Louise Wilson

Azeville

2006

Sir Eduardo Paolozzi

Michelangelo's 'David'

1987

Tate © DACS 2013

John Stezaker

Mask XIII

2006

Tate © John Stezaker

John Constable

Sketch for 'Hadleigh Castle'

c.1828-9

Tate

JMW Turner

Tintern Abbey: The Crossing and Chancel, Looking towards the East Window

1794

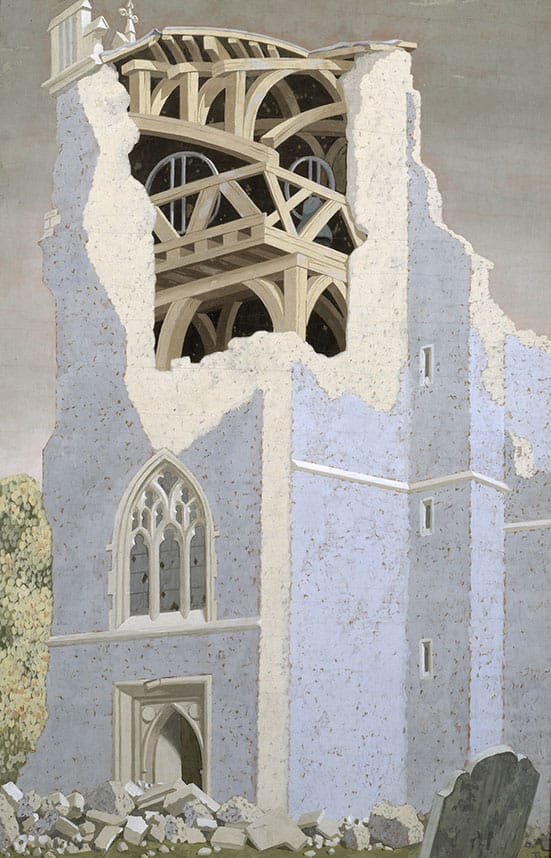

John Armstrong

Coggeshall Church, Essex

1940