4th August 2011 — 25th September 2011

Part of the Edinburgh International Festival, this dual-themed exhibition by the leading Japanese photographer renowned for his ethereal Seascapes, mythical empty Theatres and technical ability with large format works, is a somewhat disappointing affair. Undeniably beautiful as the abstract images of the Lightning Fields series are, they failed to wow me as much as I had hoped or anticipated. For, although the striking black and white prints are big, glossy and beautifully framed, they were not quite big enough; or perhaps just not granted the space that they deserved.

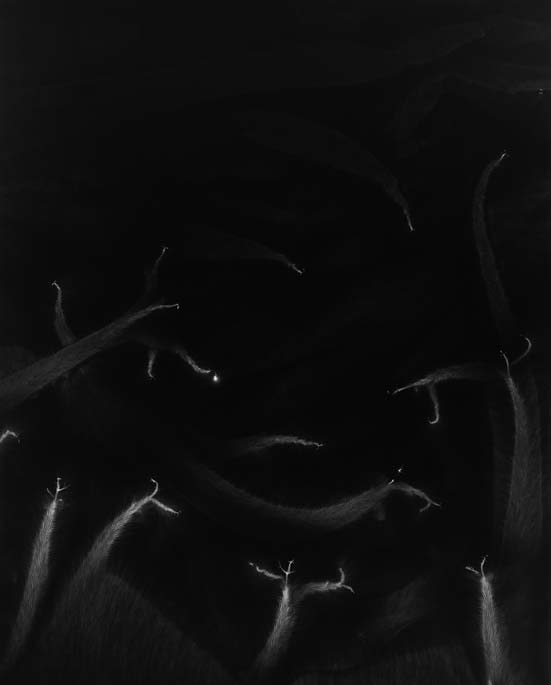

Given the subject matter and technical construction of the Lightning Fields series (whereby the images were rendered by Sugimoto sending forth a 400,000 volt electrical charge directly onto the film-covered metal plates, courtesy of a Van de Graff Generator wand) I had pictured in my head that the photographs would be of monumental proportion; as if the sheer force of the literal energy they contained could not be confined to anything less than gargantuan, yet the low ceilings of the gallery space and the close proximity of the images to each other seemed to constrict this life force and charge, which the works themselves could seemingly not contain.

Bursting out of the boundaries of the frame, these fingers and flashes of white light are transformed into fantastical scenes: nightmarish trees in an all-consuming cavernous landscape, a visual exposure of the central nervous system with its network of electrical impulses resonating from the spinal column, or an unexpected molecular composition of unlikely cells revealed under a microscope. Here, the revelation of light particles usually invisible to the human eye construct a series of interpretative possibilities which seem to provoke some kind of primordial fantasy, while celebrating the constrictions of scientific rationale. They reveal the organic, mythical and natural force of lightning captured and confined by technology; divulging a specific moment in time exposed and frozen for all to see, yet without the use of an actual camera. Perhaps it is this tension which creates the poetic violence of these beautifully stark photographs, for like Cragg’s sculptures, the physical format seems to struggle to contain the life-force beneath the surface; a force which crackles and fizzes with its desire to break out from the confines of its form.

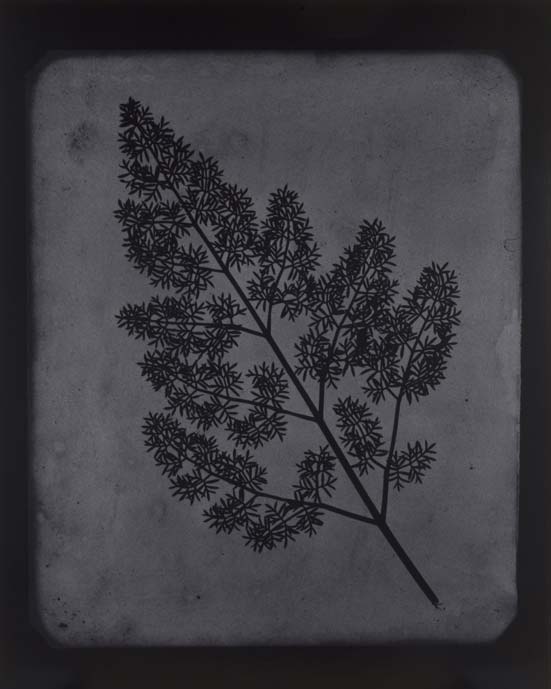

The other half of the exhibition was dedicated to Sugimoto’s Photogenic Drawing project to re-develop, re-size and re-frame a series of negatives by the pioneering 19th century photographer Henry Fox Talbot (who is credited with being the first person to develop positive prints from photographic negatives). Although pretty, delicate and often eerie in effect, with their shadowy forms softly emerging from murky backgrounds which rightly suggest a bygone era (a nice contract to the high exposure flashes of light bursting out from the Lightening Fields), this seemed to me a purely academic enterprise which belies the atmospheric success of Sugimoto’s earlier work. For, while it may be technically brilliant and historically interesting in its ability to reveal secret nuances of the images not visible to Fox in the original, I’m afraid I didn’t feel that it made for a particularly interesting exhibition.

Caroline Darke

A Stem of Delicate Leaves of an Umbrellifer, circa 1843 – 1846, 2009

Toned gelatin silver print: 93.7 x 74.9 cm

© Hiroshi Sugimoto

Lightning Fields 168, 2009

Gelatin silver print: 149 x 119.4 cm

© Hiroshi Sugimoto

Lightning Fields 190, 2009

Gelatin silver print: 149 x 119.4 cm

© Hiroshi Sugimoto