22nd July 2011 — 25th September 2011

There’s a kooky, spooky feeling to this exhibition of work by the late artist and influential teacher David Askevold. The sound of a theremin from a 2003 performance entitled ‘The Two Hanks’ and ‘Kepler’s Music of the Spheres’ (1971-74), in which snakes push ball bearings over instruments made by the artist, suffuse the gallery with cosmological and magical undertones, part schlock-horror and part new age, which have their visual counterpart in the accompanying out of focus, slow-motion video. The two Hanks of the first work – Williams and Snow, musicians both – were conjured by Askevold in a performance that lives on as an installation comprising an electric guitar, a rudimentary plywood stage and a long, bench-like box housing a speaker and supporting a monitor. Amid much strobe lighting and dry ice, an indistinct scene plays out, in which the artist performs an incantation to the Hanks, one a famous alcoholic, the other a renowned teetotaller. The work’s meaning hovers around the unrealised potential of the empty stage and the murky video document, but it’s hard to tell what was happening, or why it might still be of interest today.

References to the occult, mysticism and religion recur throughout the show: ‘Burning Bush’ (2005) is a series of photographs and acerbic drawings in which the artist sketches the moment when Satan himself enters George W. Bush, who is “too drunk to notice that it isn’t Jesus who walked in”. Askevold’s significance as a teacher at some of the most radical art schools in northern America is borne out by the collaborative works he made with artists who had been his students. The photo and text piece ‘Poltergeist’ (1979), made with Mike Kelley, links the topics of dreams, openness and teenage vulnerability to possession by evil spirits. ‘Two Beasts’ (2005-10), made with Tony Oursler, is a projection divided into 20 small boxes on continuous loop, featuring imagery that ranges from still lives of mundane household goods to landscapes, spiralling abstract patterns, drawings, body parts and, significantly, a slow pan across the spines of horror film VHS tapes. The overall effect of the piece is one of visual bafflement, with a soundtrack of what might be snippets of illicitly intercepted talk, radio static and some sort of sonic materialisation of energy itself, all shaded with a sense of impending dread.

Askevold must have been a fun teacher, though, living in a world in which a teenage fascination with the occult is processed through academic eccentricity. His work has a rough-and-ready imperfection that celebrates failure. ‘Taming Expansions’ (1971) is a photo and text piece relating an inadvertently bathetic performance in which six men stood in a circle wielding willow branches to tame six snakes. All didn’t go to plan, however, and one of the performers was bitten by a snake. As the cameraman moved to help him, he knocked over the equipment and ruined the film. The most visually splendid work in the show is ‘Nova Scotia Fires’ (1969), a collage of scenes in which fire meets the other elements: it licks the land, races against the wind and meets the sea. The mesmerising speed and movement of the film is given a soundtrack of distorted voices and radio static that feels like it was captured by the artist on a journey to outer space.

This exhibition is contextualised, perhaps unfairly, in terms of Askevold’s role as a teacher and his influence on students who went on to become much more famous than he ever was: it takes its title from a tribute paid to him by Mike Kelley and includes important works made with Kelley and Tony Oursler. Nonetheless, it also invites us into a kind of peculiar world whose apparent simplicity belies Askevold’s utter originality, and his ability to create works that continue to operate on the mind in strange and mysterious ways.

Ellen Mara De Wachter

Camden Arts Centre

Arkwright Road

London NW3 6DG

http://www.camdenartscentre.org/

Open

Tuesday-Sunday, 10am-6pm

Wednesday, 10am-9pm

David Askevold: The Disorientation Scientist

Installation view at Camden Arts Centre, 2011

Photo: Andy Keate

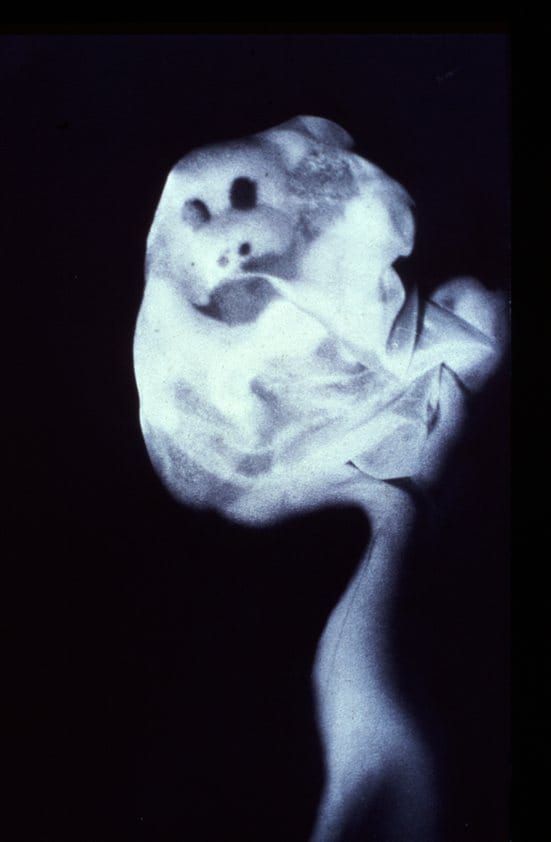

The Poltergeist, 1979 (detail)

A collaboration between David Askevold and Mike Kelley

Courtesy and Copyright David Askevold Estate

David Askevold and Tony Oursler - Two Beasts 2005 -2010

Copyright Tony Oursler

Photo credit Oursler studio

Nova Scotia Fires (1969)

David Askevold

Courtesy and Copyright David Askevold Estate