12th June 2011 — 2nd October 2011

Collection Lambert en Avignon, France

Chapelle du Méjan, Arles, France

Much has already been written about Cy Twombly’s painting during his long career, including recently, sadly due to the artist’s departure on the 5 July this year. To conclude the series of posthumous reviews about his final shows, (see the previous issue of ArtVehicle’s review of his show at Dulwich Picture Gallery), Le temps retrouvé (‘Time Regained’) was conceived by Twombly in collaboration Eric Mézil, curator of the Collection Lambert in Avignon, in the South of France, opening just weeks before the artist’s death.

Yvon Lambert, whose collection is housed in a magnificent eighteenth century hôtel in the papal city, had a very closer relationship with Twombly, having shown the artist from the late 1970s. Following a successful solo show at the Collection in 2007, the artist conceived the idea of showing a lesser-known aspect of his practice, his photographs, alongside the work of other inspirational artists-photographers. This exhibition offered the opportunity of seeing his photographs in France for the first time, but more importantly, the opportunity to discover a fascinating series of works dating from the late nineteenth century onwards. A concurrent satellite showcase of works by Douglas Gordon and Miquel Barceló took place in the Méjan Chapel at the Arles photography festival to extend the reach of the show.

As Twombly’s recent Dulwich exhibition has shown, his work had a strong engaged with literature, in this case mythology, as well as an important durational aspect. Despite at time having a spontaneous appearance, just like photography, it is actually built up through the accumulation of knowledge, technique and visual stimulus. This exhibition placed the focus on the influence of photography and the moving image, not necessarily just on Twombly’s practice, but on painting or art in a wider sense since their invention. The show offers a subtle lesson in the history of their relationships and a prism through which to discover Twombly’s works.

Following the advent of photography, sequences of snapshot of everyday life can be processed as ‘internal cinematography’ according to Henri Bergson (Creative Evolution, 1907), in an attempt to capture a fleeting sense of reality. The title of the show based on the final tome of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (1913-27): Le temps retrouvé (time ‘re-discovered’ or ‘regained’), is a reference to Proustian and Bergsonian notions of memory, those that can be recalled by the use of visual stimuli. The curators of the show seem to offer Proust, a writer obsessed by the relationship between painting and writing: ‘My book is a painting’ (as Proust wrote to cinematographer Cocteau), as a counter balance to Twombly, a painter influenced by writing: ’I need, I like emphasis ... I like something to jumpstart me - usually a place or a literary reference or an event that took place, to start me off. To give me clarity or energy.’ (Interview with Nicholas Serota, 2007). And so, the show neatly weaves in early photographic works and films, current practice, as well as literary references in order to contextualise and finally conclude with a showcase of Twombly’s recent photography.

The development of photography in the late nineteenth century had a profound influence on artists at the time, painters and sculptors alike. The show starts with stunning documentary images taken in Auguste Rodin’s studio by Charles Bodmer, Victor Pannelier and Eugene Druet. Not only do the images offer a unique record of Rodin’s studio, the marbles and plasters in progress where a mass of writhing bodies struggles to take shape in the artist’s large, airy pavilion-sized space, but they also reveal’s the artists’ foresight about the images’ potential. Indeed, the photographs show Rodin’s reworking directly on their surface, enhancing the twists and curves in the work, examining the shapes from a two dimensional and form particular points of view, probably aware of the medium’s potential to convey the dynamics of his work to a mass-audience.

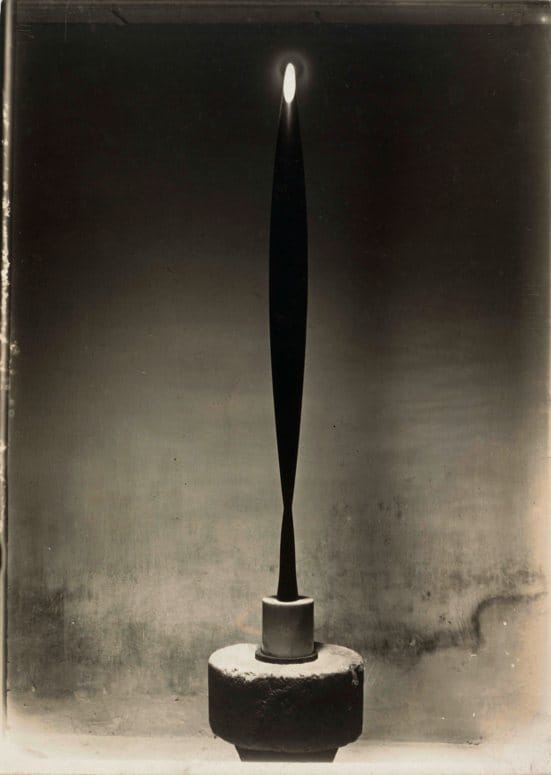

By inviting these photographer into his studio, Brancusi, like Rodin understood the power of the medium as a tool for self-promotion. However, he soon began to take pictures himself, unsatisfied with the views taken by photographers. Although technically flawed, grainy and out of focus in certain areas, Brancusi captured the interesting angles and effects of light and space on his works, focusing on certain details and unusual angles attempt to convey the object’s spatial presence.

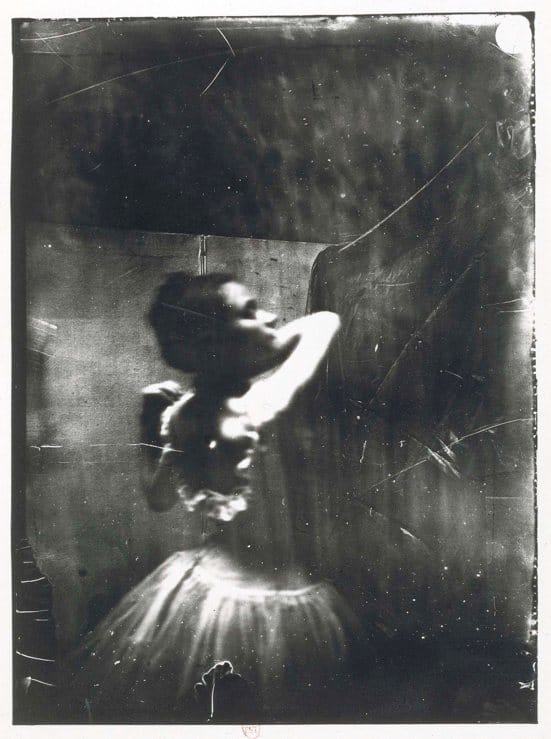

Edgar Degas, Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard’s work cannot be understood without reference to photography, capturing strange angles, snapshots of daily life. Degas, credited to be one of the first artists to use photography in his painting, his little-known photographic images of ballerinas appear like proto-solarisation images, prefiguring Man Ray and Lee Miller and by three decades.

Although the show jumps between historic and contemporary pieces, the most surprising discovery were four short films realised by Sacha Guitry at the height of WWI as part of an elogia of French culture called Ceux de chez nous (Those from Our Land) (1915/39) where Guitry has captured amongst other great French intellectuals at the time, Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, August Rodin, and even rather surreptitiously, Edgar Degas on film. Although film was a very new medium at the time, the artists seem to understand its use, not only to promote their work, but also as a method for capturing and interpreting reality, the seventh’s art as it is called in French. Indeed, although Guitry states Rodin did not understand what he was doing, as he kept talking to the camera at a time when sound could not yet be recorded, his comment “call it what you want, it will only ever be a form of photography” actually reveals his profound understanding of the new medium. Film, just like photography and painting are merely pictorial triggers for our visual memory.

Meanwhile, Douglas Gordon’s film Iles Flottantes (2008) is a tongue-in-cheek reference to the French egg white dessert, but the craniums floating in a pond seem more to point to the water lilies that Guitry captured the Monet painting in a white suit in his garden in Giverny. His inclusion at the start of the show actually prefigures his other series of ‘vanities’ exhibited at Arles. In this series, Gordon again offers an interesting bridge between film and photography, by burning the eyes of photographic portraits of the gods of the screen therefore disallowing theirs and our gaze.

An interesting parallel is made between the systemic documentations of Muybridge, Ruscha and Sol Le Witt. Ruscha’s series of aerial shots of parking lots dating from the late 1960s prefigures his later paintings, offering a startling marriage between objectivity and geometric abstraction that engenders a sense of alienation from a burgeoning consumer culture. Le Witt on the other hand carefully documented over 200 personal objects when he moved house, carefully recording them and classifying them according to an idiosyncratic archival method.

The show includes some quirky interjections of literary references such as Julia Margaret Cameron’s portrait of Julia Jackson or Virginia Woolf’s mother, portraits of Gertrude Stein including her posing next to Picasso’s portrait of her, as well as Steichen’s photo of Rodin’s Balzac. These images pop up throughout the show, in the manner of Proustian triggers, to remind you of earlier works, or to make parallels with Twombly’s.

The show also includes issues Sugimoto’s breathtaking long exposure seascapes, Louise Lawler’s mise en abîme images taken in situ at the Collection, whilst works from Cindy Sherman’s ongoing Untitled Film Still series are stalwarts in the question of representation in film and photography. Fast-forward through alternative representation of family life in Jacques-Henri Lartigue’s juvenile experiments, Diane Arbus’ portraits of atypical relatives, and finally Sally Mann’s eerie and timeless collodium-process photographs.

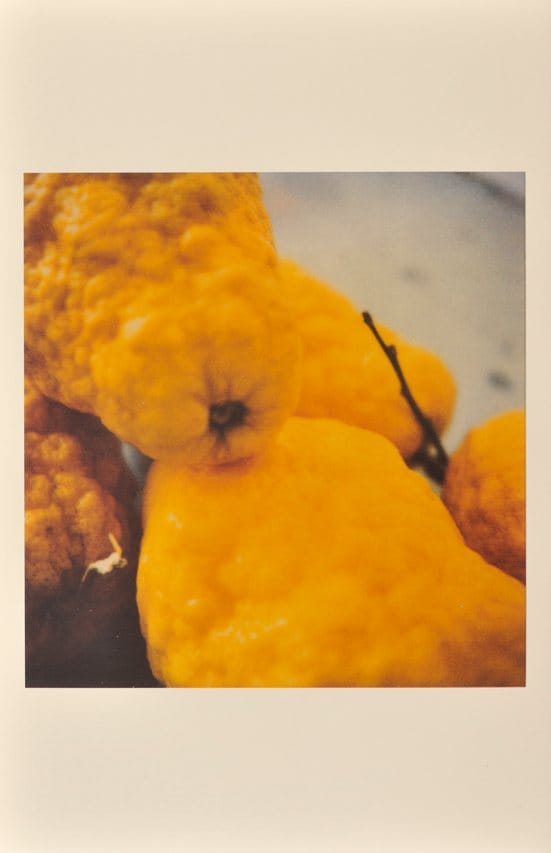

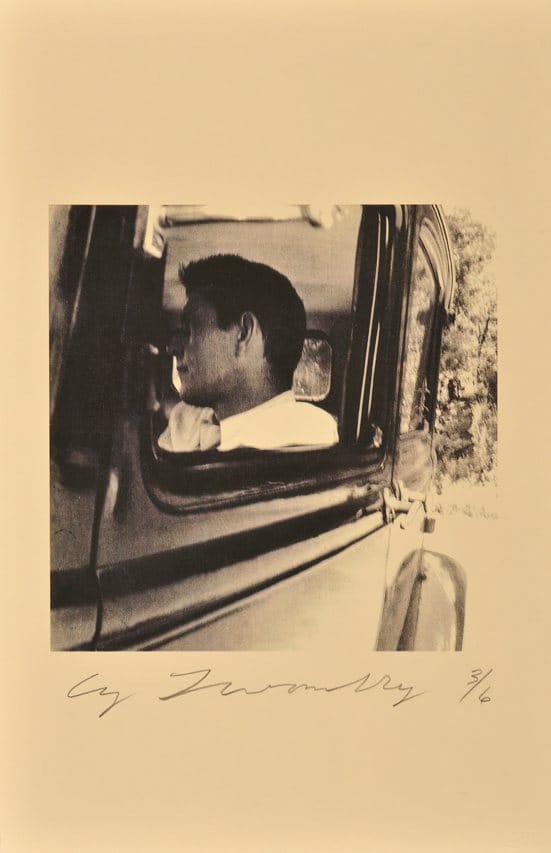

Finally we reach Cy Twombly’s work on the ground floor. His early photographs bring the scene back to Black Mountain College and the time spent with Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage and Merce Cunningham. Beautiful still lives of intensely coloured peonies and lemons then transport us to Gaeta in Italy to the artist’s residence there, followed by photos of plaster torsos and still lifes of paintbrushes in his studio. These humble scenes offer the viewer a glimpse of the artist’s personal working space and remind us of another anecdote in Guitry’s film about Monet, he asked the famous painter to give him one of his used brushes despite the artists humble disbelief of its possible future use. A simple conclusion to an unassuming tribute to Cy Twombly and a mediation on the refraction of photography in art.

Emily Butler

Flowers II, Gaeta, 2006

© Cy Twombly. Print Richard Cook

Lemons, Gaeta, 2005

© Cy Twombly. Print Richard Cook.

John Cage, Black Mt., NC, 1952

© Cy Twombly. Print Richard Cook.

Constantin Brancusi, Bird in Space, c.1936

© ADAGP / Collection Centre Pompidou, Print Jacques Faujour.

Edgar Degas, Dancer, c.1900

© Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Douglas Gordon, Self Portrait of You + Me (Signoret), 2008

© Collection Lambert / Douglas Gordon.