29th March 2011 — 26th June 2011

Do you know we are being led to slaughters by placid admirals & that fat slow generals are getting obscene on young blood Do you know we are ruled by T.V. (Jim Morrison, American Prayer, 1970) Richard Prince has a penchant for nurses, music, cars, and books. That’s not news to most of us, but the extent of his bibliomania was to me. His recent show at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, offers a unique occasion to discover gems from his personal collection alongside those of the BNF. The exhibition itself contextualises his sources of inspiration as many of his well-known works are drawn from books or magazines. By appropriating a number of printed materials, Prince’s practice questions the authorship in more ways than one, yet this exhibition actually sheds a different light on his obsession with American popular culture.

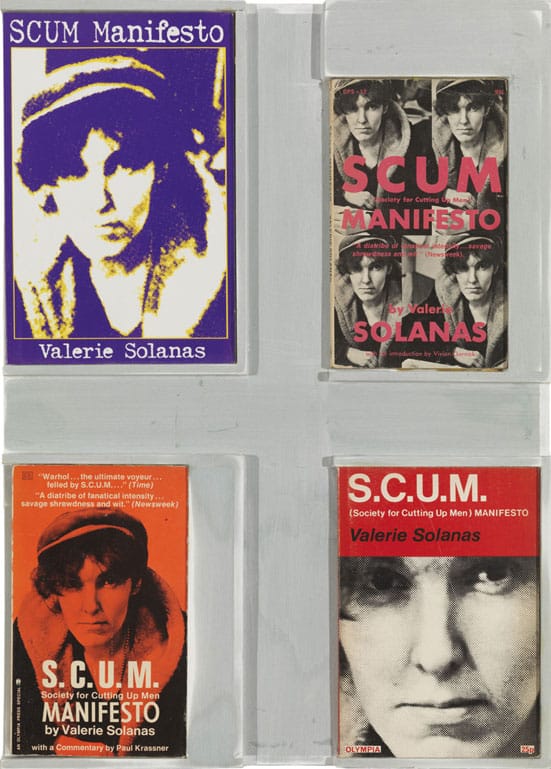

The exhibition is centred around a wooden cabin-like structure, an architectural nod to the American Anglophile shingle style and a reference to the building that houses Prince’s library - designed by Adjaye Associates no less - that features a comparative installation American/ English (see where he is going here), of US and English first editions of the same publication. The installation physically reveals the extent of Prince’s 30-year passion for collecting books. The show itself focuses on American popular culture from 1949, the year of his birth and the year George Orwell wrote 1984, and… 1984. It charts the development of soft porn novellas, Beatnik prose, the rise of sci-fi mania and cold war neuroses, then hippie, rock’n roll, punk and biker styles.

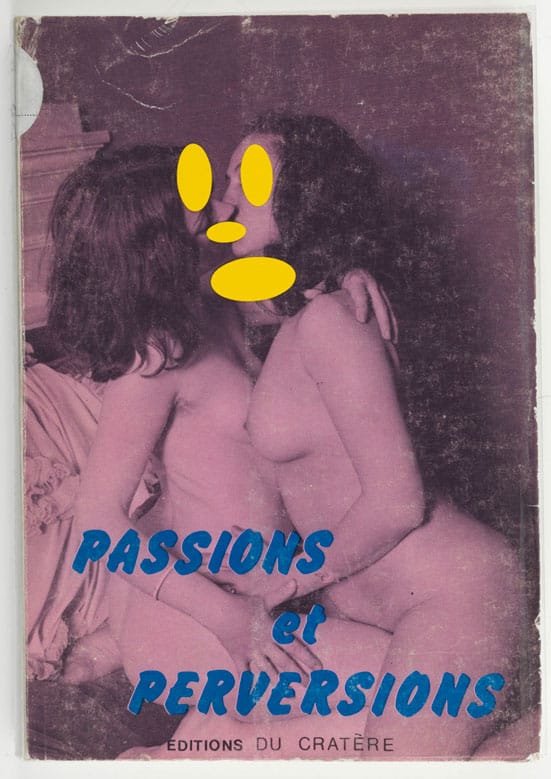

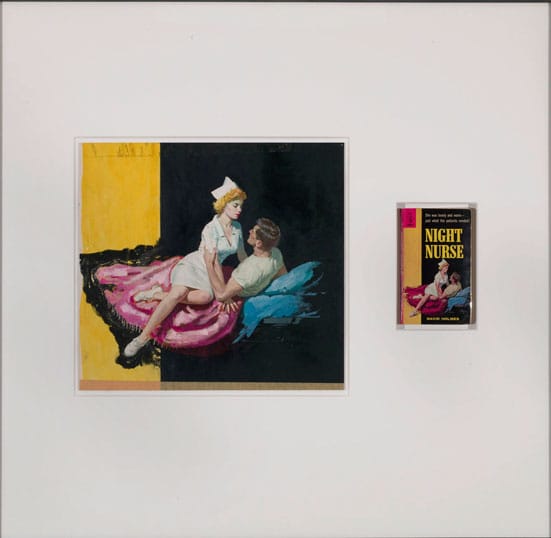

American/ English is interesting not only from a graphic design point of view, the covers of the American editions contrast with the more restrained images in the British versions, but more importantly as they reveal different facets of an epoch. Yet when you actually come to analyse them, the differences seem much the same, both reflections of a consumerist culture. However, Prince does not delve too deeply into the topic, by playing with asymmetry and scale of the specially made plinths he underlines the point that it is an installation rather than an exercise in comparative sociological book design. Prince also brings these books back into his world by displaying his extensive collection of original artworks used on their covers, aptly called Originals, which he has mounted next to the publication they were designed for in his signature-style frame.

Outside the cabin are 16 themed vitrines including: Lolita and Lollipop, Beat Hotel, Bomb Dreams, On the Road, On the Bus, Criminals and Celebrities and Sex and Drugs and Rock and Roll. Each vitrine includes signed first editions that Prince has avidly collected, but also items from the BNF’s collection, for example French first editions of his books. Yet what is the link between Gallic culture and Prince’s fascination with Americana? Few people know in fact that French publishers were the first to publish daring authors such as Rimbaud, Baudelaire, and later in the Twentieth century foreign texts such as Joyce’s Ulysses, Nabokov’s Lolita or Borrough’s Naked Lunch, key works in Prince’s collection.

In addition to putting the works into context, the show actually reveals the darker side of American culture. Indeed, the title of the show pays homage to Jim Morrison’s posthumously self-published American Prayer (1970) which offers an affecting commentary on society whose themes, despite their new age veneer, still seem as current now as they were forty one years ago. Rather than offering a glossy picture of a society at a given point in time, Prince’s collection actually points at the cracks in the status quo.

These cracks can be seen for example in Blade Runner author Philip K. Dick’s letters to friends disclosing his addiction to snuff tobacco; Bruce Lenny’s 1961 cracking title How to Talk Dirty and Influence People; Kerouac’s letters revealing his rethinking of the title On the Road in a desperate attempt to get his book published; or Jimi Hendrix’s lonely letters on hotel headed paper to his dear father while on tour.

There is no doubt about it though, Prince’s works still dominate the show. He has also added another level to his intervention by modifying a number of items from the BNF collection (on acetate covers and not the original to reassure any librarians out there), as well as producing over 450 fake books for display in a ‘reading room’ at the end of the show. In a twist of fate, the BNF’s director acknowledges that items that were once minor trashy examples of popular literature through Prince’s intervention will now become part of their rare collections.

Nonetheless, the exhibition reminds us of the importance of popular culture in a wider sense in Richard Prince’s works. Books are shown beside film transcripts, artworks, and lyrics, while the songs that feature in the display are played through speakers in the exhibition space. Apart from the breadth of the material on display, the show’s strength lies in literally enabling a re-reading of his work. His famous appropriation of Brooke Shield’s nude portrait as a pre-pubescent child by Gary Cross can be seen in a different light next to Nabokov’s first edition of Lolita. It is interesting to note by the by that this is the second time the image has been shown at BNF unlike its recent removal from exhibition at Tate Modern, London. As in his work more generally, Prince collects, appropriates, and modifies books and their readings through his interventions. Through the show, his Nurses, or biker’s Girlfriends actually reveal the perverted side of a culture that Prince holds its own mirror up to.

Emily Butler

Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Richard Prince, assemblage éphémère

sur un livre de poche: Passions et perversions,

Paris, 1974, BnF littérature et art

© Richard Prince, photo by Rob McKeever,

courtesy of Gagosian Gallery

Richard Prince, Untitled (original), 2009

Original illustration and paperback book

34 x 35 inches (86.4 x 88.9 cm)

© Richard Prince, Photo by Rob McKeever, courtesy of Gagosian Gallery

Richard Prince, American/English, 2008

Books, sintra and bondo

© Richard Prince, photograph by Rob McKeever,

courtesy of Gagosian Gallery

Installation View

© Pascal Lafay/BnF.