12th June 2010 — 26th June 2010

The Showroom

12 – 26 June 2010

Curated by the first year MA Curating Contemporary Art at the Royal College of Art in collaboration with Martha Hellion

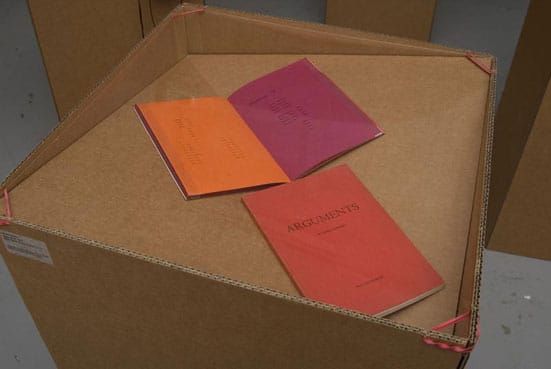

During the years that Ulises Carrión spent in Amsterdam, 1972 to 1989, he produced a wide variety of works that employed almost all the late 1960s and early 1970s forms of distribution: books, films, radio shows, print editions, mail art, conferences, talks, and festivals, calling into question the status of the artwork as a unique object and defusing single authorship by working on collaborative projects. A selection of Carrión's work was recently on view at The Showroom offering a rare occasion to have a peek into the artist's personal worlds and cultural strategies. Arranged in a modular display system inspired by the cardboard vitrines designed by Martha Hellion for the Fluxus exhibition that toured the UK in the early 1970s, the exhibition gathered a selection of Carrión's books and videos, from early books such as Looking for poetry 1973 to the video works Playing Cards Song 1980 and The Death of the Art Dealer 1982. Following the same spirit of collaboration and spontaneous gathering that characterised most of his work, the exhibition culminated with a re-enactment of The Lilia Prado Festival, a reassessment of one country's cultural values and stereotypes, and the possibility of translating them to another cultural context.

A former poet, Carrión was interested in the structural, spatial and visual potential of language. His early works such as La muerte de Miss O 1966 or De Alemania 1970 connect with a tradition of artistic and poetic practices that extends from the Cubo-Futurist and Dadaist legacies, to the Concrete and Fluxus poets of the late 1950s and early 1960s. In this tradition, language rids of its semantic burden increasing its material perception and acquiring a formal autonomy that intensifies its plasticity and objecthood. The destruction of meaning in language had a great impact in the structure of the book, which remained being a container of texts but now these could or could not be literary; they were open to the articulation of new systems of signs.

Carrión's work soon distanced itself from the literary practice to formulate the definition of 'what a book is' which is best developed in his notion of bookworks, 'books in which the book form, a coherent sequence of pages, determines conditions for reading that are intrinsic to the work.'(1) His essays, The New Art of Making Books 1975 and Bookworks Revisited 1979, are eloquent articulations of new systems by which to present language under different forms. In his writings, he appeals to the ability that everyone has to understand and create signs and systems, setting up notions of what a book is by opposing radically to the traditional genres of novel, theatre or poetry. For Carrión, every book allowed for a different type of communication, and it was the conviction that each book produced and conveyed a different effect or massage that led him to experiment with other mediums, applying the same logic throughout his work.

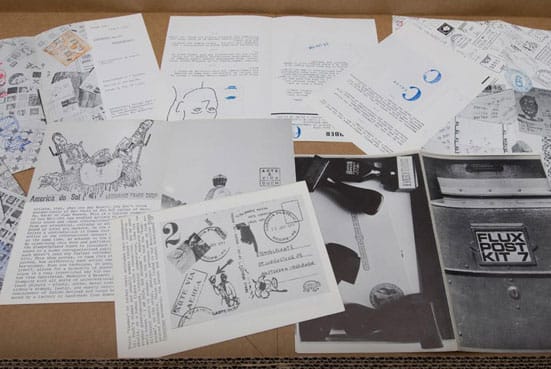

In 1975, he opened in Amsterdam Other Books and So, a bookshop specialising in the production and distribution of artist's books, an archive and exhibition space, where artists gathered, exchanged ideas, where performances, lectures and other events would take form spontaneously. Carrion's interest in the production of artist's books wasn't so much in tune with recent claims about the democratisation of the artwork, or about making it accessible to a wider public, rather he was experimenting with ways of devising an artwork that could incorporate its own distribution as a formal quality. Central to his work was the relationship between communication and distribution and with Other Books and So he felt he could have some control over the production and distribution of his own work. 'Where does the border lie between an artist's work and the actual organisation and distribution of the work?'(2) he would ask himself, reaching the conclusion that distribution should be an intrinsic part of the work because when the art work includes its own distribution it becomes something else, its form serves its own purpose. Accordingly, he organised a series of Mail Art exhibitions, such as Definitions of Art 1977 and Erratic Art Mail International System 1977, which offered an alternative to the official mail system, and where he drove the attention from the aesthetic value of the object to the fact that Mail Art was a unique way of controlling the production and distribution of art. Distribution becomes a formal element of the final work, determining its physical appearance, while at the same time emphasising the relationship between form and function.

Mail Art was also a strategy to integrate and incorporate other artists' works to his own, bringing together different views and opinions, and renouncing to just one way of representing things. Similarly, he started to experiment with different mediums, such as video and film, performances and festivals, devising what he referred to as cultural strategies in which the artist's 'personal world' would gain a social reality by being exhibited and thus becoming a cultural event. Carrión was using culture as a broader concept than art, including non-aesthetic elements, as he explained, culture was 'the coordination of a complex system of activities occurring in a social reality and including as well non-artistic factors: people, places, objects, time, etc.'(3) In Gossip, Scandal and Good Manners 1981 Carrión experimented with marginal communication, in this case, gossip. The work consisted in launching a piece of gossip with the help of a group of friends. The project lasted more than three months, and it also consisted of a lecture on gossip in the University of Amsterdam, and a video-work as a conclusion. This work contrasts with the informality with which gossip is originated and transmitted and it gives an insight into Carrion's ideas about language and communication, his fascination with identity, his interest in everyday life, and the importance of his friends in his works.

He became more interested in mass media and in 1983 he joined the founding of the Vereniging van Media Kunstenaars, the media artist union responsible for the creation of Time Based Arts. The immediacy of video gave artists more control over the production and distribution of their works. It was also a very simple media that could be used in many ways. Aristotle's Mistake 1985, a documentary in which reality and illusion are blurred, was conceived to be broadcasted in television, 'a frame that makes everything equally real. If it's on TV it's not art, it's real'(4). Once again, the distribution of the work would have an impact in the nature and formal qualities of the very same work.

In 1984, Carrión produced The Lilia Prado Festival a work that makes us reassess current art practices that engage in originating social events and that facilitate a dialogue among diverse communities outside the confines of the institution or gallery. The Festival was a tribute to the Mexican actress Lilia Prado, an idol in the Mexico of Carrión's youth, and it included the screening of Prado's films together with parties, cocktails and music. It generated extensive press coverage and attracted a great number of people. By organising this Festival, Carrión intended to raise questions on identity and cultural values, and more specifically on how one can translate a cultural stereotype; how does a star from a given culture translate to another culture with different values. With this work, Carrión activated a social situation that connected with the historical avant-garde ideal of blurring art and life, while at the same time it brought about many questions on the dematerialisation of the artwork and its anti-market nature, and more importantly, about single authorship and collaboration. He considered the Festival to be a ready-made, a work from which he could withdraw, a work that offered him the possibility to disappear: 'My ideal as an artist' he said, 'is to become invisible.'(5)

Footnotes

Carmen Juliá