25th February 2010 — 25th February 2010

In collaboration with Improbable.

A Co-Production with the Metropolitan Opera, New York.

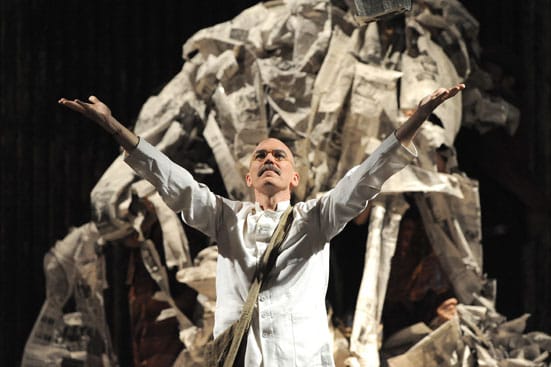

Director: Phelim McDermott. Assistant Director / Set Design: Julian Crouch.

Conductor: Stuart Stratford. M K Gandhi: Alan Oke (Tenor).

Due to an excess of pleasant but inconsequential film score

work (aka Michael Nyman syndrome) Philip Glass's reputation as a serious

composer has declined somewhat in recent years in favour of the less easily

distracted (and arguably more talented) Steve Reich. Back in 1980 however,

following his rigorous Music In Twelve

Parts and the unquestionably innovative Einstein

On The Beach, Glass was very much the Minimalist ‘Man’ and it was in this

climate that he was commissioned to compose Satyagraha.

Eventually forming the centerpiece of his ‘personality trilogy’ of Operas,

alongside Einstein and the concluding

Akhenaten, Satyagraha was Glass's first exercise in traditional orchestration

(if you overlook the fact that he entirely dispenses with the brass section).

Not that this traditional element bleeds overmuch into the provenance of the

work itself. As with Einstein (a

libretto largely consisting of chanted numerals) Satyagraha is far from strictly operatic. The, loosely told, story

is that of Mahatma Gandhi's struggle to establish and develop his doctrine of

non-violent protest during his sojourn in South Africa which, in case you were

wondering, is where the big ‘S’ word comes in (literally ‘truth force’). Moving

on from Einstein Glass decided to

have this libretto sung in Sanskrit, not (as it turns out) as big an impediment

to enjoyment as one might fear, proving to be a richly resonant language.

Moreover, as the libretto itself, the text of which was sourced from the Bhagavada Vita by Constance De Jong,

largely consists of moralistic reflections, highly worthy but prone to impart a

sense of piety fatigue after a few hours, the usage of a dead language possibly

does some of us a slight favour.

Satyagraha's non-chronological scenes

are designed to illuminate the ideals of the doctrine rather than the specifics

of Gandhi's life and each of the three acts are informed by a spiritual

guardian (Tolstoy, Indian poet Tagore and Martin Luther King) who represent an

aspect of the Satyagraha process, thus rendering the work into a non-narrative

and stylised form. It is unsurprising, then, that much of the weight of a

convincing rendition of the piece falls upon imaginative staging. And

imaginative it is. The set design is kept suitably Spartan, thus reinforcing

the meditative nature of the text and the minimalist style of the score, but

the set changes themselves create beautiful, transformative atmospheres around

the central stasis of the piece. Within these parameters great ingenuity is

displayed, principally by use of the humble newspaper, suggestive of Gandhi's poverty, and

alchemised en masse by the cast into fans, screens, barriers, fountains and

fluttering animalistic shapes (and sometimes even just used as newspapers).

Strategic use is made of imposingly large, Gollum like papier maché figures

that, at certain crisis points, loom nightmarishly above the principal

characters, representing the violence proffered by those opposing Gandhi's

cause. A particularly affecting tableau is constructed midway through

Act3, where slow stepping figures stretch simple bands of tape across the

entire stage creating a tranquilising, luminous web-like environment. A

complete mood shift is then achieved by simple dint of the tapes being slowly

cut and adeptly fashioned into a vibrating version of one of the Gollums. It

could be argued that combining slowly moving performers with slowly moving

musical arpeggios is, in this neck of the woods, an enormous 80s cliché. But,

Hell, if it works this well, why change it?

Happily the musical performances are every bit the equal of the set design.

Alan Oke's tenor (as Gandhi) leads the cast with a smooth, plaintive, graceful

tone, standing out but never overwhelming his co-singers. The declamatory

beauty of Act 1, Scene 1’s The Kuru Field

Of Justice ,which slowly evolves into a male trio and is crucial to

establishing the tone of the whole performance, is a singularly well balanced

affair containing the essential blend of strength and gentleness that could stand proxy to the moral of the work

itself.

A more contentious note is struck by the pronounced vibrato utilised by all

three female leads. An unusual call, this, as the vocal oscillations involved

sit more awkwardly over the rapid ostinato passages of the music than purer tones might. There is, however,

no doubting the quality of the chorus. Consistently precise and passionate the

full chorus of Act 1 Scene 3's The Vow concludes that section of the work with breathtaking aplomb, fair blowing the

posh sock’s off of even those of us ‘up in the cheapies’.

Minimalism has, notoriously, been

tagged as a school of composition that has failed to achieve an entirely

‘mature’ phase. In 1980 Minimalist music, while not as strange a beast as it

was in 1970, was still cutting edge stuff but, inevitably, the ensuing years

have bred familiarity. The backing music to a thousand, serious minded,

documentaries has done for the genre what L’Oréal’s make-up graphics have done

to Mondrian’s art; half neutered it. How then has the piece stood the test of

time?

A few shortcomings do make themselves apparent. Firstly, the piece is somewhat

underwritten. This much was suspected back in the day but is now more

pronouncedly noticeable. In some sections that which once seemed daringly

repetitious now seems, simply, over repeated. There is also the issue of

dynamics, or lack of. Minimalist music is something of a pig to orchestrate, as

its fundamental reliance upon repeated motifs and rhythmic emphasis is more

naturally suited to smaller and more percussively orientated ensembles (I’m

taking the mild liberty of regarding keyboard instruments as being,

essentially, of the percussive persuasion). The additive, subtractive nature of

Minimalist compositions demand that any dynamic shifts be clear, noticeable ones;

thus leaving the composer with fewer orchestral cards to play in terms of

subtle changes of timbre (Mahler ; it’s not) and the, ensuing, ‘flattening’

effect throwing considerable weight upon the primary melody lines to remain

consistently and intrinsically interesting. Given his unknown track record up

to this point in his career Glass proves himself a remarkably strong melodicist,

revealing a Coplandesque liking for wide interval spaces during Act 2 and some

shades of Gorecki throughout the largely elegiac Act 3, although it’s also in

this (concluding) section of the work that he seems, at times, to have run out

of musically inventive steam.

As I suggested at the beginning; Glass may never quite have lived up to the high hopes that were entertained of him during this period. Much of his subsequent piano compositions (for example) have been exemplary, but for all of those, there’s been too much time spent on such projects as the Low Symphony; things certain to raise profile but intrinsically unlikely to accrue any true artistic weight. Lamentable as that is; Satyagraha remains a work of great emotional power and of continuing value. A tantalising pointer, perhaps, to what might have been.

Keiron Phelan

English National Opera

London Coliseum

St. Martin's Lane

London WC2N 4ES

http://www.eno.org/

Satyagraha

Alan Oke

Company 3

Credit Alistair Muir

Satyagraha

Alan Oke

Credit Alistair Muir

Satyagraha

James Gower Company

Credit Alistair Muir