12th February 2009 — 17th May 2009

In the words of El Lissitsky, the “triumph of the constructive method” is celebrated in epic scale at Tate Modern. Greeted by two ink drawings by both artists of the ‘Constructor’, we are immediately invoked to pick up our shovel and leave the Capitalist delights of the gallery’s gift shop and café behind, walking headlong into the world of Futurist Russia.

The exhibition leads us through the key elements associated with Constructionist practice; the most exciting perhaps being the graphic and architectural rooms, showcasing the unfaltering ambition and belief in the positivism associated with the immediate post-Bolshevik era. Both artists are represented equally, with the welcomed inclusion of wonderful set design, textiles, literature, and campaign posters by fellow comrades Stepanova, Mayakovsky, Vesnin, and Exter.

Within the Constructivist movement, the work of Rodchenko and Popova embodies the Leninist endeavour to build a socialist order. Memories of the 80’s Spirograph and pick-up sticks of red and black carry strong as you walk through the galleries. A survey of two individuals working to create a rational and geometric understanding the fragmented world around them, turning their backs on the bourgeoisie past of the Tsars. Popova’s Space - Force Construction series illustrates this further; the largest in the series is a Futurist star-burst, stunning in its linear simplicity.

“The line has revolutionised our view of the pictorial surface” says Rodchenko, whose composition studies resemble the blue prints of an engineer, or the inner workings of a classic time piece; re-enforcing this image of the artist as constructor. We are shown drafts and preparatory studies by both artists; rubber smudge marks and all, permitting a sneak peek at the complex foundations which lurk beneath the seemingly flawless formalism. Such a thoughtful selection of works allows for a most deep understanding and appreciation of the technical skill involved in Constructivism. Rodchenko’s sculpture is given its own room to breathe, some casting spider web shadows against the white walls of the gallery, watched by the artist from the other side of the room; the omnipotent custodian.

A large section of the show surveys the ‘PR work‘ of Rodchenko and his close companion Vladimir Mayakovsky; featuring posters and campaigns for such diverse state-endorsed commodities as cigarettes, biscuits, rubber soles, and box office cinema (including Rodchenko‘s poster designs for Sergei Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin). Popova’s stylish, state-commissioned, textile designs for mass consumption makes the Primarks of the contemporary Capitalist high street seem all the more pitiful.

A show encompassing so much of the revolutionary use of film and media, lends itself to an offshoot film programme, which is sadly omitted. We are however able to see segments of video works such as The Female Journalist (1927), directed by the pioneering Lev Kuleshov (1899-1970), documenting the ill-fate of a woman who has fallen for a married statesman. In this enticing film, all aspects of the show pull together, a socialist amen. Kuleshov worked alongside Rodchenko, who used his knowledge and understanding of urban design to full effect, in the design of the set, and direction of the camera. The speed and motion of the whirring cogs and machinery of the printing press echo that which is represented in both artists’ matt and understated painting and painstaking line drawings, brought to life by this effective collaboration. Other filmic highlights include Dziga Vertov’s Kino Pravda and various other tit bits out in the foyer. A stab at recreating Rodchenko’s working club reading room fittingly closes this fantastic show, providing insightful source material, and a welcomed sit down after this epic journey through Communist Russia.

Judith Carlton

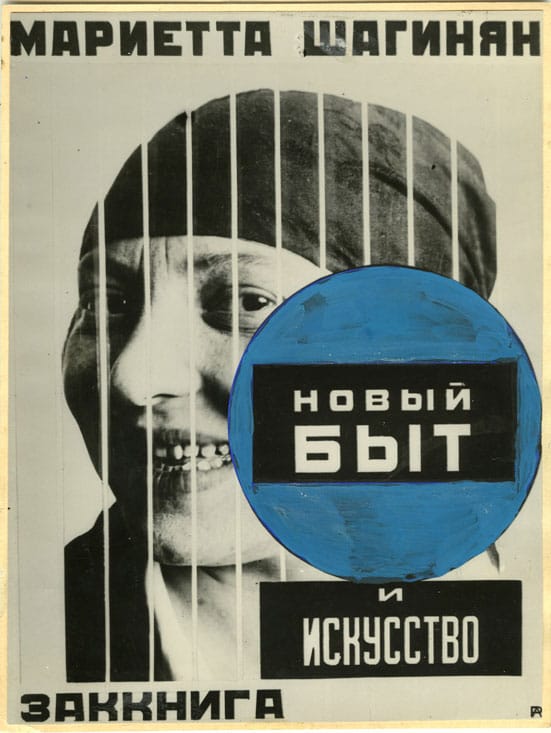

Aleksandr Rodchenko

Cover Design for Marietta Shaginan’s “Novyi byt and Art” 1923

Rodchenko and Stepanova Archives (Moscow, Russia) © Rodchenko and Stepanova Archives (Moscow, Russia)

Gelatin silver print with gouache

22.3 x 16.7cm