8th December 2006 — 21st January 2007

Reza

Aramesh, Lewis Amar, Gordon Cheung, Henry Coleman, Gian Paolo

Cottino, Dan Griffiths, Anthony Gross, Cyril Lepetit, William

Hunt, George Kontos, Steve Klee, Goshka Macuga, Cristina Mariani,

Theo Michael, Redux Project, the hut project, Theo Prodromidis,

TemporaryContemporary, Alex Zika, Jen Wu.

For the purposes

of writing this article, I did an online search of the show's

title, 'We've lost the hearts and minds...'. Here is a selection

of my results:

We've lost the hearts and minds...

of the Iraqi

people.

of ordinary Iraqis and no wonder.

of a generation of

young Muslims.

of every Iraqi and every Muslim in the world.

of most Arabs. of the Arab street.

of most constituencies

in the Middle East.

of many Americans.

of the American public.

of a swath of the world.

And the particularly astute:

We've

lost the hearts and minds...

and the arms and legs.

Between

1964 and 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson used the phrase "hearts

and minds" a total of 28 times. The expression, at the

time referring to the U.S. operation to win the allegiance

of the South Vietnamese people, has now come to mean the PR

exercise both preceding and during any military action set

in place to convince the civilian population to accept the

behaviour of its subjugators. It is no wonder the phrase has

undergone somewhat of a revival in the last four years.

The

artist and co-founder of Centrefold Scrapbook, Reza Aramesh,

has borrowed this phrase for the current exhibition at the

E:vent space in Teesdale Street. The fragment 'We've lost the

hearts and minds...' assumes that at one point we already had

them, although whose hearts and minds we had is left unclear.

Deliberately left unfinished, it implies a degree of exhausted

defeat rather than a self-assured call to arms; a suitably

open-ended starting point for the purposes of a group show.

In a letter addressed to the visitor, Aramesh explains how

he invited 19 artists, most of whom had contributed to Scrapbook

5, to address the relationship between art and protest, posing

the question, 'Can art be political?' There is a lot of work

here, some of which attempts to tackle this question directly,

some of which merely hints at it. One of the benefits of the

scrapbook is of course that visual material can complement

that on the adjacent page or indeed happily sit at odds with

it.

When I arrived at the gallery in East London (perhaps a

little too punctually for a Sunday) all the AV equipment was

yet to be switched on and I was faced with a table showing

the evidence of a late-night, drunken gambling session. In

fact, the empty chairs, table littered with poker chips, cards

and beer cans are intended to act as a metaphor for the intricacies

involved in collectively curating a group show such as this.

Group Show as Poker Game, by Temporary Contemporary hints at

the long alcohol fuelled evenings of intellectual parlaying

and bluffing with one's peers, where the object of the game

is one's personal gain - not that of the collective. You're

really only in it to score for yourself. Sod the group!

There

is a definite aesthetic to the overall show of the make-shift

and the make-do. With the dazzling yellow walls, spray-painted

crass branding and list of works scrawled onto the back wall

in black marker, Aramesh makes a strong link back to the scrapbook

format of Centrefold. As far as I can tell, this is no bad

thing. The exhibition has a slight tone of a Max Ernst collage

novel, drawing seemingly incongruous imagery together to form

a loose narrative. Collage is indeed used throughout by several

of the artists, often with nods to the surrealists. Mixing

line-drawings with newspaper cuttings, an open-mouthed chick

waits for a slew of regurgitated stories, feeding on tragedy

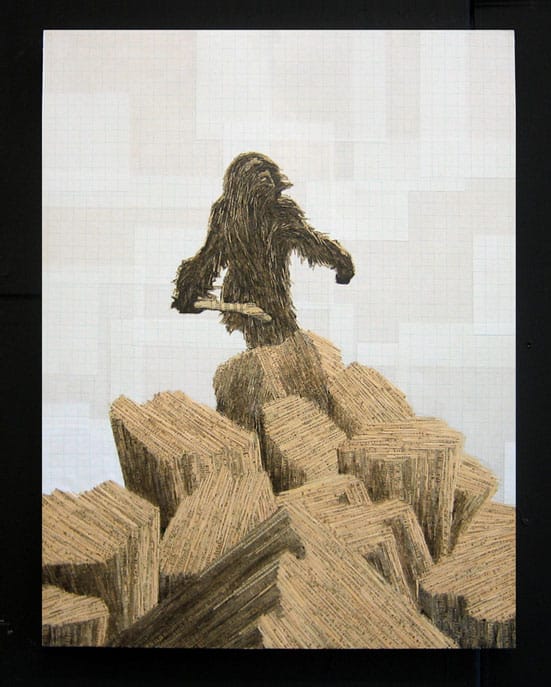

and loss in Aramesh's wall-piece. Gordon Cheung's image of

the neaderthal man with club, victorious atop a mountain of

rubble, is made up of impossibly thin-cut strips of the Financial

Times. The title, Hardcore, implies that human kind, even in

it's world conquering glory of capitlaism, is still all 'ug-ug's',

stubbornly resistant to change. It brings to mind that Banksy

slogan, strategically positioned in the path of the morning

commuter: 'Win the rat race, still a rat.'

Theo Michael's illustrations

of Arab men drawn with speech bubbles coming out of their mouths

next to George and Laura Bush in jumpers (the former with red

felt-tipped eyes), is reminiscent of Joe Sacco's graphic novel,

Palestine. Here, the speech bubbles are left empty (in the

face of U.S foreign policy, the Middle East has no voice).

The muted voice seems to be reiterated in Dan Griffiths' work,

Art is What Makes Life More Interesting Than Art. 5 images

of the familiar revolutionary symbol, the clenched fist raised

aloft, are formed through cut and mounted wood veneer. The

use of this shallow material along with the variations in the

image from one panel to the next lessens the potency of what

is a politically charged logo. They appear here as placards

without slogans, implying that protest can at times be reduced

to shouting a lot yet saying very little.

This deliberate obliteration

of text is even more apparent in St. Paul, Storyboard from

a Scenario by Pier Paolo Pasolini by Redux Project where 30

painted scenes cover the print of various pages of found newspapers.

This may be a reference to Pasolini's declarations of his leanings

to Communism on the cover of the Italian newspaper Libertà but

the narrative is hard to discern and through nothing more than

laziness, I gave up trying rather quickly. It seems I was second

guessed. In Jen Wu's Nail Text, a photograph of hand, the fingernails

painted white with tip-ex, rests on the page of some academic

text (apparently some critical inquiry of French anti-colonial

essayist, Frantz Fanon). Words on the page are partly obscured

by the artist's fingertips, onto which has been written 'Bore'

and 'Deviate'. When read as running into the body of text, "Bored

the Marxist theme..." and "Deviated from anything",

it reveals a world-weariness and lacklustre attitude to engage

with ideas. Wu asks an important question here: Are we really

bored with socialism, too preoccupied to effect change? The

viewer can share in this apathy. Like notes in the margin of

a borrowed book, it is someone else's outlook we can choose

to take or leave.

I was similarly bored waiting for the 6 video

pieces to come on, played in a clockwise sequence of monitors

in the centre of the space. I'm sorry to say I missed the majority

of them in my impatience. This is a shame as the snippets I

caught of Theo Prodromidus's film, Serenade to Spectacle, looked

promising, as did Lewis Amar's Of Land & Tilte, whereby

a comic character runs, trousers down, through the grounds

of stately homes, much to the guffawing delight of the onlooker.

The varying fragments that spilled over heightened this sense

of the fragmented narrative of the scrapbook collage.

Historically,

scrapbooking was a tradition similar to storytelling, but with

a visual rather than oral, focus. However, I felt there could

have been a little more explanation in some areas and I was

irritated by having to keep going back to the map of the gallery

on the wall to cross-reference works with their titles. Even

so, the artists here do well in answering the call of Aramesh

in the show's curatorial remit and it is refreshing to see

a group show of emerging artists that has such coherence. However,

don't expect to find any easy interpretations.

SP

E:vent

96 Teesdale Street

London E2 6PU

http://www.eventnetwork.org.uk/

Open

Friday-Sunday, 12am-6pm

Gordon Cheung

'Hardcore'