1st November 2006 — 21st January 2007

Walking

into the David Smith show in the Tate Modern you first have to

navigate your way around the queues for Carsten Holler's metal

slides and the shrieks that follow those descending into the turbine

hall. These cries remain and don't get any quieter until you have

reached the third room. But it is ok, because the second room is

dedicated to Smith's 'Medals for Dishonor' and these are equally

over-dramatic and theatrical, like the rides and riders. The occasional

yelp helps as we are meant to view these wall-mounted metal reliefs

of human atrocities as his Guernica or perhaps Grosz's.

This exhibition

celebrating the centenary of Smith's birth serves to remind us

of his vital role in the changing shape of sculpture in the 20th

Century. When I fist saw the Surreal influenced busts in the first

room, such as 'Saw Head' and ' Widow's Lament,' I had an awkward

memory of Tony Hancock's 1961 film 'The Rebel.' In the film Tony

Hancock (played by Tony Hancock) creates grotesque parodies of

Picasso sculptures such as ' Aphrodite at the Waterhole" and

is seen cycling his bike over his Pollockesque splatter painting.

At this point I didn't feel that that the exhibition was really

doing a good job of reminding of the greatness of David Smith.

The 12 pieces in the third room are much more interesting as they

are viewed as a field of mainly spindly upright forms, the weight

of the work is also suddenly made apparent as is the endless brown.

Even the more delicate sculptures, with sections defined by thin

curving rods, have an underlying drag of gravity about them. There

is a vantage point in this room where you can see through into

Room 5 and the piece 'Hudson River Landscape' flattens itself out

against the white walls and looks not unlike a version of Duchamp's

'Large Glass.'

Initially I was disappointed how the rooms were

bland with white walls and unambitious lighting. They don't seem

to be making true icons of the sculptures or aiding them in their

desperate need to be outside. Ok, so there isn't a sculpture garden

at the Tate (yet, I suppose), but so many of the sculptures rely

on being in/with Nature. Smith himself talks of how he burnishes

the steel so that they can reflect the blues and greens of the

skies and the mountains and how the effect of natural light falling

on the sculptures is so important.

It is in the room with the 'Tanktotems'

and 'Sentinels', tall 'personages,' that you come across his direct

link with Abstract Expressionism. It is with the reds, greens,

and yellows that have been blotched onto pieces like '51/2' that

make them exciting. (Even though each sculpture in the room is

penned in with a wooden rail running around it.) He is often seen

as the Modernist sculptural Pollock and when Smith jokes at the

end of the exhibition that all of the 'Sentinel' pieces that surround

his house are female another likeness strikes. This machismo and

fuck and fight stance is imbued in all the works, even those pertaining

to be dealing with the psychoanalytical.

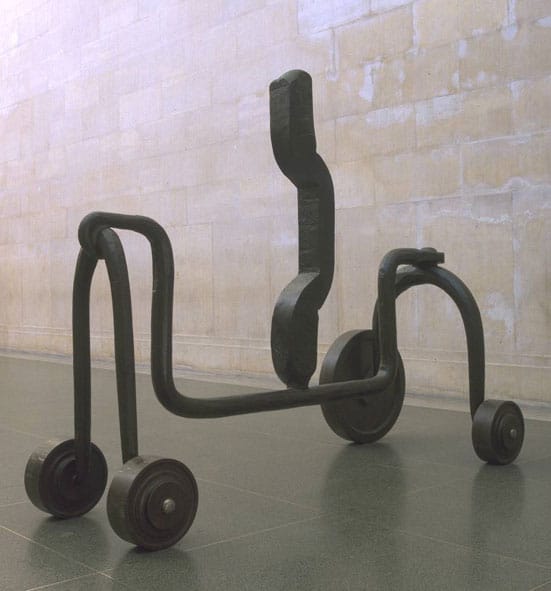

The 'Wagons' and 'Voltri'

sculptures of the 1960's make part use of scrap metal that return

to the readymade quality of the agricultural tools used in the

'Agricola' series a decade earlier. These later pieces on wheels

made me think of what John Chamberlain was to do in the decades

following with his car parts. In fact Smith starts using car spray

on these later sculptures that give a flat plain of surface colour.

When the works start to look slick, like the burnished, hollow

and shiny 'Cubi' that it becomes hard not to notice the aftermath

clots of metal where the sections have been welded together. They

need these traces of where the sculptor has been, it retains their

painterly quality - and it maintains an ongoing sense of the artist

as 'worker.'

The whole show is engrained in the past, it is art

making in a certain point of history; this way of production seems

so distant, but is only 40 years ago. By the end of the exhibition

what I really wanted to see were more of his drawings, he started

his artistic career as a painter and the drawings he made were

vital to the manifestation of the sculptures.

'I feel no tradition,

I feel great spaces.' Its funny that he should say that as now

the opposite seems truer - this exhibition is wholly lacking in

great spaces; there is tradition throughout.

BT

Tate Modern

Bankside

London SE1 9TG

http://www.tate.org.uk/modern

Open

Daily, 10am-5.50pm

David Smith

'Wagon II'

1964

Steel sculpture

Tate. Purchased with assistance from the American Fund for the Tate

Gallery, the National Art Collections Fund and the Friends of the Tate

Gallery 1999

Copyright: Estate of David Smith/ VAGA, New York, DACS 2006