'The Reader' forms one of a number of projects that Guestroom, a publishing and project space run since 2002 by artists Maria Benjamin and Ruth Höflich, is currently organising to examine reading, libraries, collections, and variant habits of their use. This research includes 'The Librarians', a series of video interviews with artists and writers who address their work and practice according to their book collections; and 'Reading Room', another series of videos that shows artists reading aloud from individually chosen texts. Both projects formed an event as part of the ICA's 'Nought to Sixty' programme, in which the abovementioned videos were shown alongside performative readings on a built-up stage that shifted its form according to each text. Images from the event and stills from the videos are included in 'The Reader', which as a tidemark for a research programme in flux, is also a coherent and articulate publication in its own right. The book is unrestrained in its commingling of historical material and contemporary references, many as re/movable as the signage in the Warburg Library, ('Always check that no one will be squashed before moving the rolling stacks') and the current state of the Senate House rennovation.

There are various threads that unite the book, predominantly the question of arranging information deposits. Maria Benjamin's 'This Shelf' describes the schematic line-up of her fiction books (Sartre and de Beauvoir do not sit together), as Francesco Pedraglio examines of the legacy of Aby Warburg's indexical systems (including the famous 'Mnemosyne Atlas'), an essay which is then complemented by Rebecca Bligh's historical and personal mapping of The Warburg library, one of four essays by Bligh under the rubric 'Libraries of London'. Bligh's texts are highly researched, quite fascinating and also very funny evocations of the rituals and peculiarities of these London libraries: the cold sweat at a British Library enrolment interrogation for example, or the gasping sweat of the stairs to Senate House.

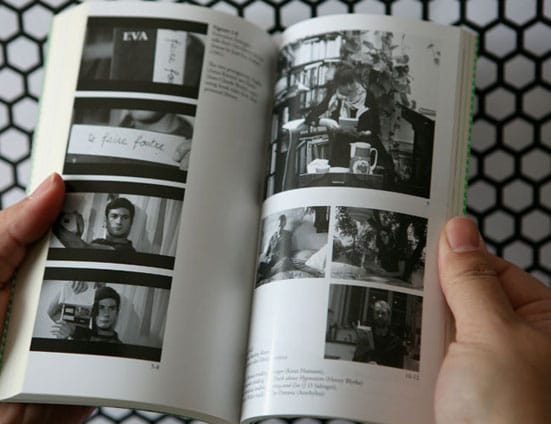

A strength of this book is its refusal to posit any dispute between the word and the object or the word and the image. Instead, it poses that these relationships are not only indivisible, but also ground for abundant creative and personal possibilities. The abovementioned 'thread' is visualised by two series of photographs by Ruth Höflich. The first, 'Same Difference', shows collections of books with aesthetically similar covers, and the second, 'from A to B', shows various book spines that when arranged together hold poetic and thematic resonance, (Falling Man, You Shall Know Your Velocity, Surfacing, To the Is-land, being one series). These photographs are then complemented by Francesco Pedraglio's selection of stills from Godard's 'Une Femme est une Femme' (1961) in which a pair of lovers argue, their dialogue built by held-up books and their titles.

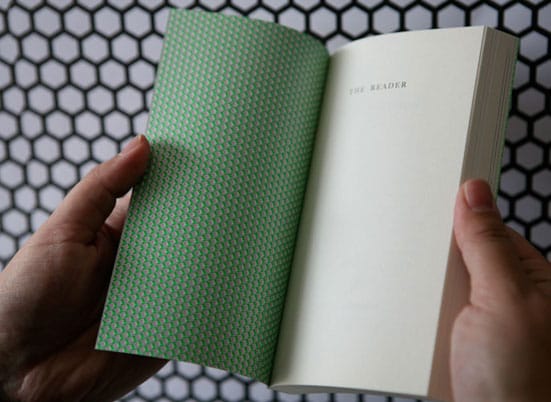

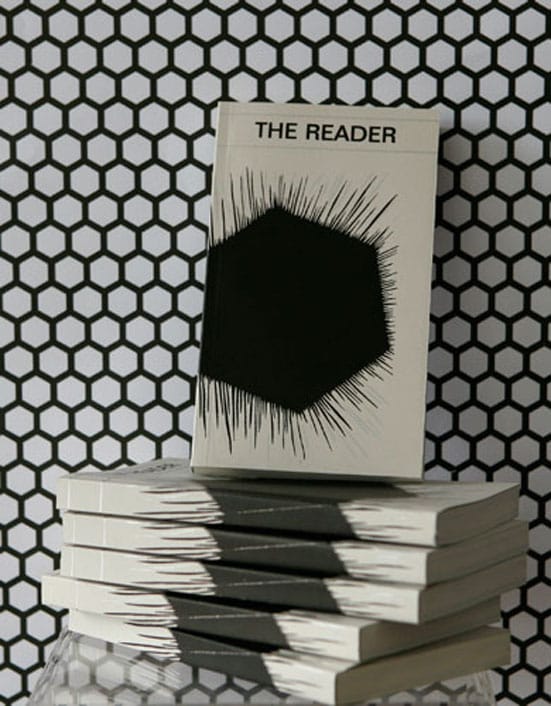

Just over 170 pages long, and made in an edition of 150, the fusion of text, object and image within 'The Reader' extends to the seductively screen-printed cover that my book-designer housemate points out is a stylised replica of a Penguin edition of 'The Outsider' by Albert Camus. Given that Maria Benjamin admits to having nine copies of the novel on her shelf, this title choice and cover demonstrate homage to Camus' thorny novel. 'The Reader' includes an experiment in reverse-ekphrasis from Tom McCarthy, who has numbered the margin of pages from Alain Robbe-Grillet's 'The Dressmaker's Dummy' and made corresponding sketches that visualise Grillet's words; and two slippery texts by Hilary Koob Sassen that reflect the overloaded knowledge systems they often describe, wobbling towards collapse and full of nonsense-wisdom: 'A sphericaldigital google cathederal earth map mosaic-flipped outside-in', being an example of Sassen's vivid phrasing. Nick Laessing contributes a text on the adventure of research, in this case on the mysterious Viktor Grebennikov and his impossible (and improbable) aeronautical experiments, and Laura Cull's 'What is a Library?', whilst packed with theoretical reference to the philosophical question she asks is an independent text itself. After an extensive glossary of online resources is the reproduction of an e-mail to Guestroom describing plans for a future electronic library: an effective 'To be Continued'.

Considering a pile of books might be daunting, it might prove how little you know. But that would be defeatist. This book demonstrates that any deposit of information should never represent a deficit of knowledge for a subject, rather multiple possibilities. Such possibilities, whilst being personal and habitual, are also community forming. This is a great book, and I like it very much.

Gemma Sharpe