Adrian Heathfield and Tehching Hsieh

Published by the Live art Development Agency and the MIT Press, 2009

Yesterday Waldemar Januszczak wrote a ferocious review of Tate Britain's latest 'Triennial' exhibition. From what I can tell he holds it responsible for his falling out of love with British contemporary art. Whist I can sympathise with this I am disappointed that his attack took quite such a vitriolic form ('The Tate Triennial is the achievement of a curatorial dunce' and so on, see what I mean for yourself http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk ). I was reassured to find it wasn't just me that was astounded when I heard him defending his views on Radio 4 this morning. I've fallen out of love with art before too - too materialistic, too pointless, too elitist, too commercial etcetera et cetera - but I've never stopped trying to believe in it.

Reading Out of Now has reassured me that I'm not the only one struggling to understand and take meaning from art. Although this book focuses on Tehching Hsieh's lifeworks (from the 1970s to 2000) there is poignancy in Adrian Heathfield's attempt to get to the crux of his art, to find out why he made it and what it meant retrospectively.

The book seems to take the traditional monograph format (big, heavy, smells good) until you actually start reading it ... the first deviation from this is in Heathfield's introduction he says: 'Often when I read a story with a name in it that is hard to say my tongue trips and I lose the thread.' I know what he means - even Tehching knows what he means; when Hsieh first started making art as an immigrant he adopted the westernised name of Sam. The book focuses on each lifework in turn and is narrated from a second hand witness' vantage point, illustrated and then contextualised with letters from contemporaries - admirers and detractors alike and is concluded with an essay by Carol Becker.

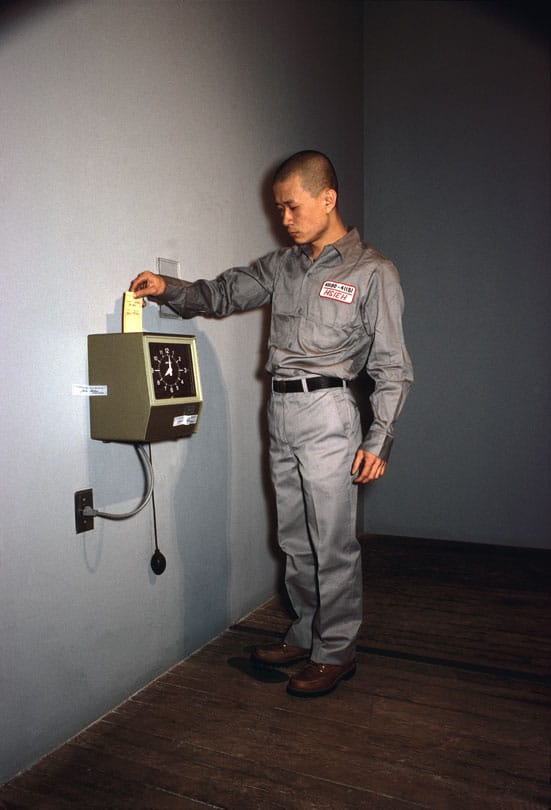

One letter included, written to Hsieh states: 'You are brining shame and discredit to the Chinese people. Go home to Taiwan' whilst another, sent during One year Performance 1980-1981 (during which Hsieh attempted to punch a workers' time clock in his studio ever hour), politely - and with every effort not to offend - pleads for an explanation of his work:

'Why do you do such performances? They do not seem self- fulfilling or such as to give much pleasure of insight to audiences, but there must be much more to them than is apparent. Please try to let me know.'

This request is echoed throughout. I'm not sure that any book, or exhibition, could ever answer, but this one certainly tries. And in doing so presents rich and textured arguments into many possible 'whys' doing justice to Hsieh's work and leaving it ultimately up to the reader to decide. There can't ever be any definitive meaning for art for anyone except its own creator. We all interpret differently and it is these nuances which Heathfield captures - sharing with us his attempts to understand and make sense, including his own one day re-enactment of One Year Performance 1981-1982 (during which Hsieh roamed New York without shelter for a year).

Hsiehs' work is fascinating, profound and mysterious. For example in Out of Now there are pages of photos of the tapes which recorded the dialogue between Hsieh and Montano (during Art/Life One Year Performance 1983-1984). Although photographed these tapes are sealed and no one is meant to ever hear them - let alone transcribe them.

I suspect it is this lack of sympathy for an audience (or is it respect?) that has, to some extent, exacerbated Januszczak (who claimed it would take over 24 hours to view all the work in the exhibition at the Tate). But this is exactly what appeals to me about Hsieh's work as it is tenderly presented here. At last art isn't presented in a defence of itself. Heathfield in this book has created, in Becker's words:

'...a frame for the documentation of Hsieh's work and all the elements of its process - a safe holding environment, where the work can rest, where the artist's actions as well as his words about them become the centrepiece and where writers like myself and other artists can attempt to think around the edges...'

Samantha Bond

Tehching Hsieh One Year Performance 1980-81

Photograph and C. Tehching Hsieh