Pulling up my hood is wonderful. I'm snaillike, peering out from within – protected, directed and incognito. The world is tenderly framed by the arc of cloth at the peripheries of my vision, easing the load of information to take in as if for a skittish shire horse. It covers my ears, too – muffling the harsher frequencies. It's a softer, warmer place that comforts in familiar ways – as womb, bed, hug, disguise – but also in an allusive manner as a sort of original architecture. Erected in an instant, it's a a tent to conjure an inside out. It smells comfortingly of me, turning me in to an environment. The snail analogy is accurate: it's a cloth hermitage, my hood, with me standing slightly back from the mouth of the cave, unseen in the shadows and observing with impunity. So, disguised as a tent, I can slip through London staring too long at passing faces, camouflaged against my own identity; something spectral and vaguely portentous. My hoodie is black, as is almost everything I wear, and I suppose that this uniform sobriety is a kind of temperance for what I worry to be an all too tender and colorful me. Someone said I looked like a cat-burglar in mourning, which somewhat destroyed the state of dispassionate remove I might cultivate.

Still, London is the perfect place to practice a charged anonymity – even though it's an anonymity that comes with it's own political category. Rather than make me mourn the doffed caps and pseudo notoriety of village life, I've found the unsigned existence afforded by a city to be welcomely conducive to introspection and not a little humility.

*

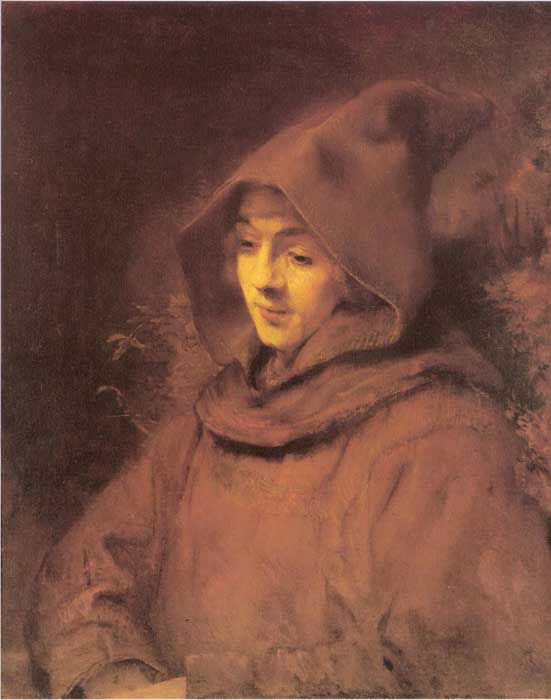

The history of hoods and whether they are viewed as aggressive or meditative seems to depend on whether they are viewed from without or phenomenologically from within. The experience of wearing a hood is distinctly at odds with the experience of seeing someone wearing a hood, somewhat similarly to sunglasses. Unless practical, a hood is an affectation that is self-assuring by being deliberating frustrating to others. A monk might wear a hood in this manner, deliberately removing themselves from social convention, emphasising their recast devotion to God, rather than society. Watching Philip Gröning's 'Into Great Silence', it's clear that the Carthusian monks at the heart of the film are concerned – traditionally and in line with many other ascetic religious lifestyles – with abstinence for the sake of complete divine absorption; with the hood functioning as a bridle in parallel with their chosen monastic isolation. The great silence of the title is the void left by casting aside society at large and thereby distraction – but it is also as an intimate silence engendered by the hood, making the wearer focus inwards, presumably in order to question themselves. The silence is a pressure, a weight, that might conjure a simple contrary motion to the diminution of external distractions: an amplification of some inner sound or vision.

Historically, observing someone else wearing a hood, however, has an altogether more negative connotation of deception, secrecy and forbidding. The isolation – as experienced – affords a meditative introspection, provokes apprehension in others. It's easy to equate such deliberate evasiveness with straightforward criminality through fearfully questioning the need to conceal yourself – an assumption that is particularly prevalent recently. In this sense, normative representations of oneself are synonymous with – perhaps even demand – openness, which is itself linked to a politics of clothing and western liberal ideals of partial undress as a site of that liberality. A hood (or, to a greater and notably different extent a hijab or burka) auto-ostracises, casting the wearer into a paradoxical state of being conspicuously inconspicuous – encountering at best ambivalence from society in general. This isn't necessarily unwelcome. The sense of alterity generated by wearing a hood is certainly part of the lure for some – myself included. Choosing to censor other's access to me, however modestly, is a means of asserting freedom, as well as a purely taciturn stance. When my hood is up I am to a certain extent illegible, and that illegibility is deliberately remiss of conventional categorical or demographic assumptions.

*

The Grim Reaper's habit is a perversion of modesty. Covering nothing but dessicated bone, it's practical value is undermined, leaving only the function of obscurity and portentousness to justify wearing it. It's a corruption of a monk's dress: borrowing the divine aspect, while debasing its fundaments. As seen covering Death's head, the hood loses its experiential possibility to his unwavering pursuit of the void, and becomes a solely observed phenomenon. What it's like to be Death is as unimpeachable a conundrum as it is with Thomas Nagal's bat, so any empathetic notion of introspection or warmth is impossibly distant. I imagine the prickly seams along his skull snagging slightly on the inside of the hood as he moves.

Ed Atkins

Fancy dress Death

'Titus as a Monk', Rembrandt, 1660

An empty hoodie