In this country, the convention for translating the dialogue of a foreign film is to use subtitles. Unless it’s animation, in which case it’s dubbed. The difference seems consistent with the original: the animation was dubbed to begin with (the cartoon characters can’t speak), whereas the live-action film’s sound was produced, recorded concurrently to the images. Dubbing live-action has always seemed to me to be slightly disingenuous – parochially minded in an unempathetic sense. Eliminating the sound of foreign speech simply because it’s unintelligible discounts everything else inherent to that speech: pitch, timbre, its synchronisation with movement and expression, its foreignness. In fact, if there is a reason for the different translation treatment of live-action and animation, it is surely to do with a weird propriety for the sanctity of the individual. However, the fact that the convention of live-subtitled/animation-dubbed is not upheld elsewhere around the world has always puzzled me.

Watching a Studio Ghibli film recently, I noticed that, unusually, there was an option on the DVD to watch with either subtitles or dubbing. Naturally I plumped for the subtitles. Why? Thinking about it, I wonder whether it isn’t slightly egotistic to opt for subtitles. A little intellectual perhaps. I can read fluently enough, and maybe subtitles complicate the filmic experience in a satisfyingly robust, adult way. I suddenly wonder whether I’d even have rented this cartoon if it weren’t Japanese but American instead. Subtitles ally cinema with literature, and in so doing textualise the experience, lending it something of the aura of the written word. The effect of subtitling a cartoon, for example, seems to be to mature it somewhat. If I were ten, I’d definitely go with the American dubbing starring Claire Danes, Billy Crudup and Billy-Bob Thornton; whereas now I find it adulterous to hear a southern-states accent coming from an Iron-age Japanese monk. It’s something to do with what is authentic about the film – or rather what is authentically the film – that creates this dichotomy: an aesthetic truth that should be maintained. Dubbing is, to my biased mind, something akin to a philistine act of defacement. The translation – performed via dubbing or subtitles – has a backwash, flooding the original with its differences, and I suppose that, the apparent discretion of subtitles as opposed to dubbing is a way of practically damming that contamination with the boundaries of a detached, non-diagetic, and silent piece of text. Temporally and spatially they exist apart from the film, appearing in sentences to be paced and voiced internally by each viewer.

The text that punctuates a silent film might lend some historical context to subtitling. Functioning in an even more literary capacity, those textual asides always seemed to me like captions beneath an illustration, only inverted: the text illustrating the film, appearing occasionally and at worthily textual moments – usually as speech, though also as narration, or to convey shifts in space or time (‘Seven months later’ or ‘London 1648’ for example).

Herzog’s ‘Fitzcarraldo’ was on TV the other day, and I was struck by how convoluted the translation process was. The films had obviously been shot without adequate sound-recording equipment for whatever reason – practical, I should imagine. After the event it was dubbed, in German and by the original cast, though not well enough to evade detection. Subsequently it had been subtitled in English, and that was how I was watching it. It’s possible that this process of dubbing originatively, so to speak, accounts for the fact that much of Europe and Asia elects to dub their imported films rather than subtitle them. Maybe it’s purely a matter of being accustomed to one method or another.

Martial arts films are almost always dubbed. ‘Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon’ appeared in both dubbed and subtitled versions in this country. That decision seems a pretty transparently market-driven exercise, with the studio realising that here was a film that straddled two usually detached demographics: the art-house audience, and the action/kung fu fans. That it’s obvious which group would go for subtitles and which for dubbing is telling. There’s a righteous affect to the use of subtitles that has a weirdly post-colonial feel to it: a textual and unobtrusive – territorially – apology on the screen. The respect that subtitles seem to signal isn’t, though, merely sensory. Remaining ‘faithful’ to the original – at the expense of mass appeal, or even mass intelligibility – attempts to avoid the pitfalls of jingoism that the speech-‘censoring’, through dubbing, of another culture might convey. Foreignness is most easily recognised through speech, through language, and it is a constant source of embarrassment to the English-speaking world that we don’t, on the whole, bother to learn how to speak to others in their native tongue. This hangover from Imperialism perhaps throbs most acutely in our (the English) psyche, and the subtitled gesture is as discreet and low a bow as possible in order to assuage both our guilty history and our persistent ignorance.

Mel Gibson’s ‘Apocalypto’ has been a consistent source of repulsion and attraction for me ever since I first saw it. It strikes me now that Gibson’s undeniable, teetering hubris is matched only by the conceitedness of his wide-eyed western guilt. He wrote the film in English, had it translated into a seldom heard Mayan dialect – which the film was spoken in – then burned his own, original, English script along the bottom-edge as subtitles. It's an audacious loop, and one which serves both Gibson’s striving for authenticity, and the need to pay his respects to a society that were completely eviscerated (though not necessarily in Gibson’s gory sense) by western ‘civilisation’. At the same time, Gibson’s script as we perceive it – in English and in subtitle – is seemingly written to be spoken by contemporary white Americans, complete with its idiom and slang. Ancient Mayan’s stalk the jungle spouting jokes about bollocks one minute, listening to the village elder the next. The irony of Gibson’s ‘respect’ is familiar and crushing.

Ed Atkins

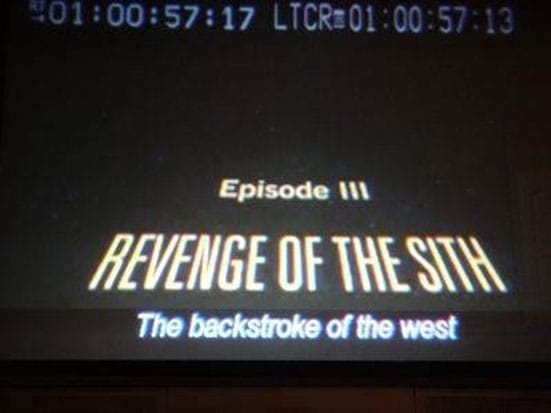

Via Mandarin dubbing, then back to English subtitles

American dubbing: "This tastes like donkey piss!"