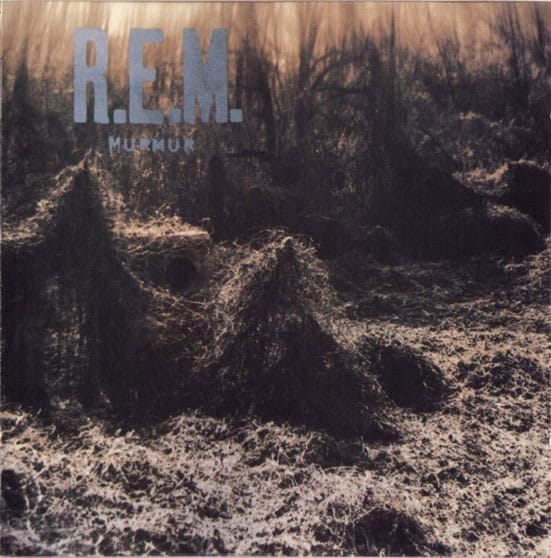

The first pop album I bought of my own volition was R.E.M's 'Out of Time'. I'm pretty sure it was an almost completely arbitrary selection, based on the cover, the name (appealing to my prepubescent precociousness, no doubt), and the category of ‘alt. rock’ perhaps. It wasn't a bad introduction to pop-rock at the time – rescuing me from a potentially middle-aged youth of classical 'hits', recorder playing and radio 4 – but it was equal parts baffling, exotic and decidedly straightforward. I learnt all the songs to an obsessive degree, and subsequently went back to R.E.M's earlier albums – 'Murmur' in particular – and began to plot my own skewed genealogy of rock from there. Perhaps because of this idiosyncratic introduction, I've always been drawn to lyrically pretty opaque stuff – Michael Stipe's lyrics, delivered in an incantatory drawl, pre-empted any coherent understanding by being both thematically and linguistically indiscriminate, positively inviting misinterpretation and, in me, mispronunciation. Long strings of verse interpreted with confidence by my immature reasoning, tested incessantly by singing their curious forms into square holes, and convinced that 'sounds-like' is the sole test of accuracy. Words that I had surely never heard before – slang, names, geographies, maturities – were inaccessible, and were replaced by me with their juvenile rhyming counterpart. Meaning in lyrics (beyond syntactical, grammatical meaning – and even these were known to be sacrificed for the sake of rhyme) was never a necessity, but instead it was the voice and the music that conjured the sentiment – the sound that infected me. Even today – firmly on the other side of a lyrically affected adolescence – I tend to enjoy songs whose meaning is enigmatic, perhaps confounded by a contradictory diction or a difficult sound; voices that attest to themselves before convention, almost certainly at the expense of easy interpretation. The extreme examples of this are songs sung in another language. I remember going to see a Bolivian band called Rumillajta with my brother and parents when I was about 8. They played panpipes, guitars, drums, wooden flutes, ukulele-like charangos, and they sang. After the gig, my parents bought one of their albums on tape – called something like 'Tierra Mestiza' (sp) – and it became a firm favourite on long car journeys. After a few months, I could sing along to the majority of the songs on the album, in concert with the singer but on the terms of pure sound, music; rather than the lyrics and linguistic meaning. I can still remember one song in particular, which had a particularly catchy, repetitive chorus which went something like this: "Shit-uss be light-ah fear-eh-sa hansubuy nassus-chai like-u" before moving on to the urgent "I like-u like-u tantamoo nassus-chai like-u", which formed the central hook of the song. These words – smashed, re-inflected and strung together with insensitive emphasis by my performance, are nevertheless translated into some sort of mutual understanding; remaining as words with meaning if only through the legend of their original performance, or the preserving effect of my emulation, uncomprehending or not; and still enveloped in the melody and rhythm of the original. In the state that they adopt in my head, the sung lyrics are the most empathetic sounds on the record – identifiable as a voice, a man, a narrative, a subject – but not a meaning in a linguistic sense. I sing along as if in tongues, relinquishing meaning in favour of (or out of a necessity for) sentiment, owed to the vocal delivery and the accompaniment – the music in the music, and not the words. It might sound fluffy, ambient; but really it’s the conviction of the performers taking precedent, rather than the immutable text.

Hip-hop, that most lyrical of musics, also has a long and baffling history of inscrutability for me. Again, it starts when I was listening as a child – less desperate to understand the intent of the rapper than to accurately match their delivery, sonic and demeanor. In a similar fashion to my infatuation with Rumillajta, there was a certain amount of exoticism, albeit more illicit, in my listening to hip-hop – a manifestation of a kind of rebellion against my own, musically seemingly restrained upbringing. Aggressively chanting and gesturing along with Warren G’s ‘Regulator’ was no less convincing and important an action because I didn’t understand the lyrics. Perhaps it was a case of a symptomatic reaction to the perceived culture of hip-hop, but I understood, heedless of lyrical meaning, that hip-hop was dangerous, cool and somehow offensive. Like an unruly child repeatedly bellowing ‘FUCK’ because she knows it draws a uniquely shocked reaction from the adults in her life – but has no idea what it means – I understood these songs without understanding their linguistic significance, but rather the affect they had on myself and others.

As a symptom of listening to the same song over and over again, learning lyrics is also the learning of another person’s vocal idiosyncrasies. Singing along with Björk one cannot help adopting her weird, pseudo-cockney accent and her stuttering inflections. In fact, listening to her, you might imagine she has no idea what she’s saying – her English lyrics seeming to be meticulously plucked from the pages of dictionary – but rather that she has sought out, and perhaps found, the linguistic rhyme for her musical intent, rather than a required communicative meaning. The intimacy of this act of singing words, rather than what might be declared in speech – and the singularity of the individual perspective and recital – make for the real listening experience. An affinity with an other that they instigate but seems to be constitutive and exemplary of our own experiences. Rumillajta, despite singing from a completely different culture and in another language, are in concert with their listeners, linguistically understanding or otherwise – fundamentally engendering musical conversance with their cause, themselves.

A good friend of mine once taught me a few Italian phrases ahead of a trip I was making to Venice. Quite quickly we were both bored with the idiom of formality – of toilets, drinks, hotels and public transport – so we moved on to some more exotic stuff. For example (and most memorably), “L’arte rapresenta il sommergibile dell’io”(sp)*. I learnt this off by heart, and subsequently went around repeating it to anyone who’d listen, relishing the rolling consonants and the gaping vowels of another language I was impersonating so strangely and so intimately, and – almost – without any understanding. Nowadays, that’s a large part of the allure of learning lyrics: in order to confirm my intimacy, my ignorance, my love of them.

* ‘Art represents the submarine of the self’, or something to that end. Though I have no real idea of the spelling or how on earth to engineer the appropriate context (or indeed how to react to the inevitable ‘che cosa?’), I feel confident and intimated with something uniquely foreign by chanting this weird mantra.

Ed Atkins

Rumillajta, circa The Eighties

REM Murmur