Recently, my father died of cancer. And although this was sudden (and yet protracted, as modern death tends to be), and afforded little time to 'prepare' – he left behind a vast body of work through which one might posthumously get to know him better. In life he produced (writing and drawings mostly) constantly, though this fact could only really be construed; he was also what one might describe as pathologically modest – although 'modest' is surely too banal a word for something so holistic in its negativity. Modesty as we colloquially practice it, often suggests a veil of negativity – a loose-fitting and perhaps deliberately not-very-convincing disguise for a genuine pride beneath, a cosset for both the subject and their audience. With dad, it's clear that this was performed almost completely antithetically. For him, modesty was the positivist pall (albeit folded over, shrivelled), behind which lurked not a faithful pride but a truthful and terrible void, a seemingly insurmountable negativity that prevented his ever admitting – to himself, let alone to us, his family – that he was, in fact, good – brilliant. This fact, at least, is beyond objective question. We have all known it for years. He was and always was a genuine and extraordinary talent whose work, glimpsed behind fast-closing cupboard doors and plan chest drawers, was utterly tantalising.

Of course, he knew that as soon as he died we would have to look. Without him standing guard, it was only a matter of time. We would joke about this around the dinner table, in the manner that one can only joke about something so absurdly distant as a death. He would confess, when pushed to recount his day, to the predictable decline of a drawing he was working on; or he might mutter something about such and such anecdote being worthy of going in the diary – and we would pounce on him, hungry for the slightest crumb of insight into his creative world. The diary in particular took on near mythical proportions. He had, we knew, been keeping it since he was sixteen. We also knew about the cupboard he kept every volume of it in – beside the airing cupboard and above his hoard of drawings. Teetering hardbacks, jostling for space. Beyond that, who knew? The joke of death only increased at the ludicrous prospect of ever reading it; his death made even more unimaginable because of the Herculean task it would bestow on us, his poor but ardent, posthumous readers.

This proves too much. The conditions of our admittance having been met, looking through the diary is very difficult. Unlike the raft of drawings (which we rifle through with awe, grinning – dividing, selecting favourites; gifting some, framing some – all of them tangible), the colossal diary is almost completely insoluble. Where does one begin? At the beginning? At the birth of his first child? Marriage? Or is it only manageable in fragments? – aphoristic nuggets and sound bites chiselled off the monolithic whole and savoured as the persistence of a perspective from when he was alive: one dazzling glimpse at a time. I discovered very quickly that I was incapable of browsing a volume without desperately searching for my name – seeking, as a mourner might, some sort of intimate correspondence with the dead; to find a loving consolation, I suppose. A mistake of course, demonstrating perfectly the significant problems with using a diary as a medium for remembrance: Alighting on my name, I read the sentence either side. It describes a fifteen-year-old me dashing out to the pub immediately after dinner, deferring some family obligation. Dad writes (and this isn't a direct quote): “nothing gets in the way of one of Edward's nights out”. A mild expression of grievance, but it knocked me for six. And I came rushing to the devastating conclusion that, in actual fact, he had hated me; resented me, even. A preposterous inference from something so banal, perhaps (and one that surely belies the unpredictability and inanity of manifest grief), but it nevertheless shattered any illusions I might have had regarding the contents of his diary. Herein are his truths, all of them. From domestic to pitch black. And this momentary insight, regardless of its triviality, lays bare this fact like a wound. The loss of an ideality is something that, so soon after a death, seems unbearable. For now, in the most part, retrieving and maintaining a memory from before – before the illness in particular – is of paramount importance, regardless of its accuracy. In this way I am for now resigned to and comforted by nostalgia.

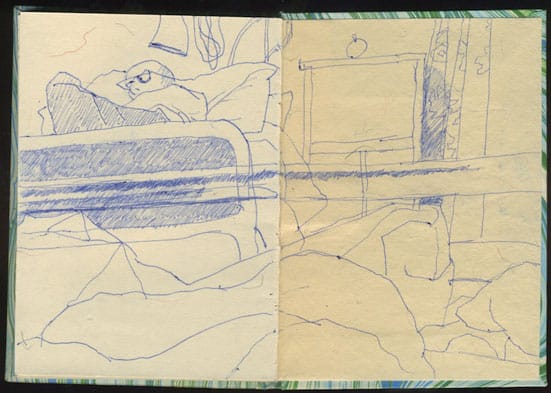

The only part of dad's diaries my mum, brother and I have so far truly read and understood are the slim notebooks he kept throughout his illness, written almost daily right up until his death. They are meagre compared to their healthy, voluminous antecedents – but they are all the more poignant for it. Much like the rest of his diary, they are brutally, painfully honest, describing in astonishingly uninhibited terms, his terrible decline. Our ability to approach them lucidly is, however, singular in its calm. For although they are certainly no less unflinching in their confessional than the rest of his diaries, they represent a parallelism to our own perspectives that could only really occur under such horrible circumstances. His increasing infirmity meant a steady and inexorable relinquishing of his own agency – perhaps the most devastating blow for so private, so independent a man; a betrayal of soul by body, he was stripped bare, so that the truths previously kept subterranean in the diaries were exposed to the day and to our frightened gaze; as well as to the cold scrutiny of myriad doctors, nurses and orderlies. The inscription of this betrayal, in the diary as on his body, is very, very painful to read – but, crucially, not impossible. In fact, for me at least, it is almost cathartic. In his chronicling of his illness and his desperately reluctant capitulation to the indignity of dependence, he affirms his agency rather than resigns it. The writing of the diary (as well as the drawings that form an appendix to it) up until the bitter end is as an act of resistance, of defiance. These notes transcend their subject matter precisely because of that subject's objective and all-conquering ubiquity – both through it having been unavoidably witnessed by others, and in the awful, universal pervasion of cancer. He is documenting something that is happening to him – not a life led. He is not in control, as no one is in control of their death, but as he approaches it he has the skill and the dignity to record it with humour, irony, sadness, joy and humanity. And, although he would have found this very hard to admit, I think he knew this.

Ed Atkins

The view from the hospital bed, a drawing from the back of the diary.